Flies are insects of the order Diptera, the name being derived from the Greek δι- di- "two", and πτερόν pteron "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwings having evolved into advanced mechanosensory organs known as halteres, which act as high-speed sensors of rotational movement and allow dipterans to perform advanced aerobatics. Diptera is a large order containing an estimated 1,000,000 species including horse-flies, crane flies, hoverflies, mosquitoes and others, although only about 125,000 species have been described.

Hemiptera is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising over 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from 1 mm (0.04 in) to around 15 cm (6 in), and share a common arrangement of piercing-sucking mouthparts. The name "true bugs" is often limited to the suborder Heteroptera.

The Pentatomoidea are a superfamily of insects in the suborder Heteroptera of the order Hemiptera. As hemipterans, they possess a common arrangement of sucking mouthparts. The roughly 7000 species under Pentatomoidea are divided into 21 families. Among these are the stink bugs and shield bugs, jewel bugs, giant shield bugs, and burrower bugs.

A proboscis is an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a vertebrate or an invertebrate. In invertebrates, the term usually refers to tubular mouthparts used for feeding and sucking. In vertebrates, a proboscis is an elongated nose or snout.

The decapod is made up of 20 body segments grouped into two main body parts: the cephalothorax and the pleon (abdomen). Each segment may possess one pair of appendages, although in various groups these may be reduced or missing. They are, from head to tail:

The Asilidae are the robber fly family, also called assassin flies. They are powerfully built, bristly flies with a short, stout proboscis enclosing the sharp, sucking hypopharynx. The name "robber flies" reflects their expert predatory habits; they feed mainly or exclusively on other insects and, as a rule, they wait in ambush and catch their prey in flight.

This glossary of entomology describes terms used in the formal study of insect species by entomologists.

Insect mandibles are a pair of appendages near the insect's mouth, and the most anterior of the three pairs of oral appendages. Their function is typically to grasp, crush, or cut the insect's food, or to defend against predators or rivals. Insect mandibles, which appear to be evolutionarily derived from legs, move in the horizontal plane unlike those of vertebrates, which appear to be derived from gill arches and move vertically.

The mouthparts of arthropods have evolved into a number of forms, each adapted to a different style or mode of feeding. Most mouthparts represent modified, paired appendages, which in ancestral forms would have appeared more like legs than mouthparts. In general, arthropods have mouthparts for cutting, chewing, piercing, sucking, shredding, siphoning, and filtering. This article outlines the basic elements of four arthropod groups: insects, myriapods, crustaceans and chelicerates. Insects are used as the model, with the novel mouthparts of the other groups introduced in turn. Insects are not, however, the ancestral form of the other arthropods discussed here.

The mouth is the body orifice through which many animals ingest food and vocalize. The body cavity immediately behind the mouth opening, known as the oral cavity, is also the first part of the alimentary canal, which leads to the pharynx and the gullet. In tetrapod vertebrates, the mouth is bounded on the outside by the lips and cheeks — thus the oral cavity is also known as the buccal cavity — and contains the tongue on the inside. Except for some groups like birds and lissamphibians, vertebrates usually have teeth in their mouths, although some fish species have pharyngeal teeth instead of oral teeth.

The mandible of an arthropod is a pair of mouthparts used either for biting or cutting and holding food. Mandibles are often simply called jaws. Mandibles are present in the extant subphyla Myriapoda, Crustacea and Hexapoda. These groups make up the clade Mandibulata, which is currently believed to be the sister group to the rest of arthropods, the clade Arachnomorpha.

In arthropods, the maxillae are paired structures present on the head as mouthparts in members of the clade Mandibulata, used for tasting and manipulating food. Embryologically, the maxillae are derived from the 4th and 5th segment of the head and the maxillary palps; segmented appendages extending from the base of the maxilla represent the former leg of those respective segments. In most cases, two pairs of maxillae are present and in different arthropod groups the two pairs of maxillae have been variously modified. In crustaceans, the first pair are called maxillulae.

Insects have mouthparts that may vary greatly across insect species, as they are adapted to particular modes of feeding. The earliest insects had chewing mouthparts. Most specialisation of mouthparts are for piercing and sucking, and this mode of feeding has evolved a number of times independently. For example, mosquitoes and aphids both pierce and suck, though female mosquitoes feed on animal blood whereas aphids feed on plant fluids.

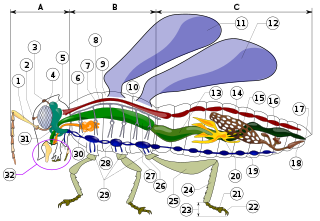

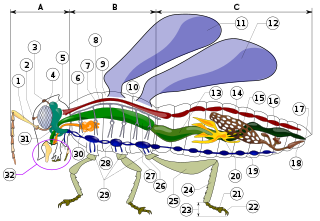

Insect morphology is the study and description of the physical form of insects. The terminology used to describe insects is similar to that used for other arthropods due to their shared evolutionary history. Three physical features separate insects from other arthropods: they have a body divided into three regions, three pairs of legs, and mouthparts located outside of the head capsule. This position of the mouthparts divides them from their closest relatives, the non-insect hexapods, which include Protura, Diplura, and Collembola.

Dipteran morphology differs in some significant ways from the broader morphology of insects. The Diptera is a very large and diverse order of mostly small to medium-sized insects. They have prominent compound eyes on a mobile head, and one pair of functional, membraneous wings, which are attached to a complex mesothorax. The second pair of wings, on the metathorax, are reduced to halteres. The order's fundamental peculiarity is its remarkable specialization in terms of wing shape and the morpho-anatomical adaptation of the thorax – features which lend particular agility to its flying forms. The filiform, stylate or aristate antennae correlate with the Nematocera, Brachycera and Cyclorrhapha taxa respectively. It displays substantial morphological uniformity in lower taxa, especially at the level of genus or species. The configuration of integumental bristles is of fundamental importance in their taxonomy, as is wing venation. It displays a complete metamorphosis, or holometabolous development. The larvae are legless, and have head capsules with mandibulate mouthparts in the Nematocera. The larvae of "higher flies" (Brachycera) are however headless and wormlike, and display only three instars. Pupae are obtect in the Nematocera, or coarcate in Brachycera.

Zigrasimecia is an extinct genus of ants which existed in the Cretaceous period approximately 98 million years ago. The first specimens were collected from Burmese amber in Kachin State, 100 kilometres (62 mi) west of Myitkyina town in Myanmar. In 2013, palaeoentomologists Phillip Barden and David Grimaldi published a paper describing and naming Zigrasimecia tonsora. They described a dealate female with unusual features, notably the highly specialized mandibles. Other features include large ocelli, short scapes, 12 antennomeres, small eyes, and a clypeal margin that has a row of peg-like denticles. The genus Zigrasimecia was originally incertae sedis within Formicidae until a second species, Zigrasimecia ferox, was described in 2014, leading to its placement in the subfamily Sphecomyrminae. Later, it was considered to belong to the distinct subfamily Zigrasimeciinae.

Haematopinus suis, the hog louse, is one of the largest members of the louse suborder Anoplura, which consists of sucking lice that commonly afflict a number of mammals. H. suis is found almost solely on the skin surface of swine, and takes several blood meals a day from its host. H. suis has large claws that enable it to grasp a hog's hair and move around its body. It is easily seen without magnification, being 5–6 millimetres (0.20–0.24 in) long. H. suis has a long, narrow head and long mouthparts adapted for sucking blood. It is the only louse found on swine. H. suis infestation is relatively rare in the US; a 2004 study found that about 14% of German swine farms had H. suis infestations. Due to the frequency of feeding, infected swine become severely irritated, often rubbing themselves to the point of injuring their skin and displacing body hair. Particularly afflicted hogs may become almost completely bald and, in young hogs, the resulting stress can arrest growth, a cause of concern for farmers.

In entomology, the term labellum has been applied variously and in partly contradictory ways. One usage is in referring to a elongation of the labrum that covers the base of the rostrum in certain Coleoptera and Hemiptera.

Proboscipedia (pb) is a protein coding gene in Drosophila melanogaster.

Perothops is a genus of false click beetles in the family Eucnemidae containing 3 species. They are known as beech-tree beetles or perothopid beetles. They are small as they are only 10–18 millimeters long. It is the only genus in the monotypic subfamily Perothopinae. They are dark-colored beetles that are found across the United States, generally in forests. The genus was discovered by Johann Friedrich von Eschscholtz in 1836. It used to be considered a family not part of Eucnemidae. The genus's name is from Greek, translating to "maimed/crippled eye" or "eye of little necklaces/bands", referring to the placement of perothopid eyes.