This article needs additional citations for verification .(January 2024) |

| Empecinados | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader | Diego Ponce de León Francisco Javier de Elío |

| Dates of operation | 1807–1814 |

| Allegiance | |

| Motives | Restore the Oriental Province to the Spanish crown |

| Active regions | Uruguay |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Reactionary |

| Status | Defunct |

| Allies | |

| Opponents | |

The Empecinados were a royalist guerrilla group in modern-day Uruguay that opposed the May Revolution. The movement started soon before the outbreak of the Independence War and had a central role in the royalist resistance at Montevideo. Despite their absolutist ideas, they took their name from the liberal Spanish caudillo Juan Martín Díez (nicknamed "El Empecinado") as a symbol of anti-French resistance and of loyalty. [1]

The movement was born in a context of widespread political conspiration caused by the aftermath of the British invasions of the River Plate. After the emergence of carlotist and liberal factions, those who preached a strict allegiance to the Supreme Central Junta gathered under the leadership of sergeant major Diego Ponce de León, a navy officer who had close relationships with the local government and was a fervent street propagandist. [1]

The movement was central in the support to Francisco Javier de Elío's self-proclamation as viceroy, what merited Ponce de León a position at the local government and the full support of his paramilitary actions by the ruler. [1] Ponce was the formal leader of the movement, and the second-in-command was Matías Larraya. [2]

The empecinados started to undertake violent activities after 1810, year in which they began to use their official name. The movement would intimidate those who supported the May Revolution and install a sort of White Terror, that ranged from mere threats to straight banishment or hanging. [1]

The movement also made use of propaganda to secure royalist support in the city, including the distribution of pasquinades and the proclamation of public speeches. [1]

The empecinados carried out extrajudicial activities and collaborated with the recently established Public Security Tribunal. The movement supported the expulsion of rebels from the city, and presented lists of alleged conspirators to the government asking for their punishment. [2]

Its members were mostly civilians, despite some were related to the Royal Navy where Ponce de León had made his career. The movement was present among all social classes, and was deeply influential among the poor people and the governmental militias. Contemporary sources point that members of the group received money and gifts from Ponce de León as a prize for their allegiance. [1]

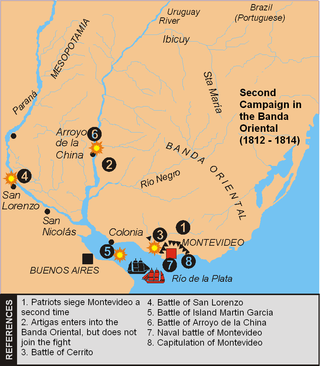

The movement's popularity peaked under the Second Siege of Montevideo when they supported a radical resistance policy of strict loyalty to the crown as the most radical faction of the loyalist side. The empecinados saw themselves as the "true Spaniards" and refused to surrender to the revolutionaries, organizing mass demonstrations during negotiations in order to sabotage any possibility of armistice. [1]

Francisco Acuña de Figueroa described an empecinado riot in his diary, stating that: [2]

Singing martial anthems as well, more than two thousand people wander through the streets tonight. With no class distinction, all of them are shaken by the same fury and enthusiasm: the fury of the offense, and one can only hear the resounding cries "to war!" "to war!" [2]

Rumours of a empecinado takeover of the city had spread soon before the peace treaty that ended the First Siege of Montevideo, but the uprising was never carried out. After the surrender at the Second Siege, however, a mutiny broke out among the popular militias who refused to let the revolutionaries take the city, but Ponce de León persuaded them to stop and obey the new authorities. [2]

There are almost no later mentions to the group after the fall of Montevideo, what points to a dissolution of the movement and a most likely imprisonment of its military adherents. [1]