The Decapolis was a group of ten Hellenistic cities on the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire in the Southern Levant in the first centuries BC and AD. Most of the cities were located to the east of the Jordan Rift Valley, between Judaea, Iturea, Nabataea, and Syria.

Jerash is a city in northern Jordan. The city is the administrative center of the Jerash Governorate, and has a population of 50,745 as of 2015. It is located 30.0 miles north of the capital city Amman.

Hippos or Sussita is an ancient city and archaeological site located on a hill 2 km east of the Sea of Galilee, attached by a topographical saddle to the western slopes of the Golan Heights.

The miracles of Jesus are miraculous deeds attributed to Jesus in Christian and Islamic texts. The majority are faith healings, exorcisms, resurrections, and control over nature.

Gergesa, also Gergasa or the Country of the Gergesenes, is a place on the eastern side of the Sea of Galilee located at some distance to the ancient Decapolis cities of Gadara and Gerasa. Today, it is identified with El-Koursi or Kursi. It is mentioned in some ancient manuscripts of the Gospel of Matthew as the place where the Miracle of the Swine took place, a miracle performed by Jesus who drove demons out of a possessed man and into a herd of pigs. All three Synoptic Gospels mention this miracle, Matthew writes about two possessed men instead of just one, and only some manuscripts of his Gospel name the location as Gergesa, while the other copies, as well as all versions of Luke and Mark, mention either Gadara or Gerasa. The "Gerasa" reading is problematic, because Gerasa is neither near a sea nor does it border Galilee.

The Yarmuk River is the largest tributary of the Jordan River. It runs in Jordan, Syria and Israel, and drains much of the Hauran plateau. Its main tributaries are the wadis of 'Allan and Ruqqad from the north, Ehreir and Zeizun from the east. Although the Yarmuk is narrow and shallow throughout its course, at its mouth it is nearly as wide as the Jordan, measuring thirty feet in breadth and five in depth.

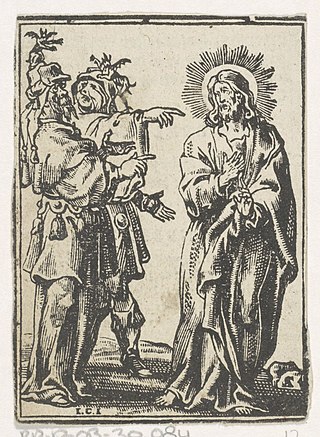

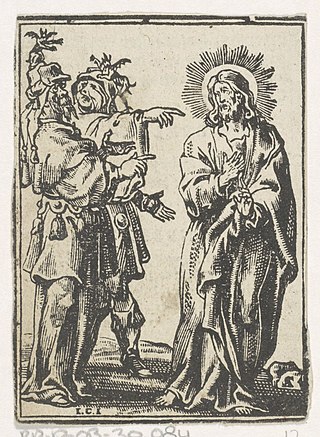

In the New Testament, Legion is a group of demons, particularly those in two of three versions of the exorcism of the Gerasene demoniac, an account in the synoptic Gospels of an incident in which Jesus performs an exorcism. Legion is a large collection of demons that share a single mind and will.

Mark 5 is the fifth chapter of the Gospel of Mark in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. Taken with the calming of the sea in Mark 4:35–41, there are "four striking works [which] follow each other without a break": an exorcism, a healing, and the raising of Jairus' daughter.

Irbid or Irbed is a governorate in Jordan, located north of Amman, the country's capital. The capital of the governorate is the city of Irbid. The governorate has the second largest population in Jordan after Amman Governorate, and the highest population density in the country.

Matthew 8:28 is the 28th verse in the eighth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament.

Kursi is an archaeological site in the Golan Heights containing the ruins of a Byzantine monastery and identified by tradition as the site of Jesus' "Miracle of the Swine". Part of the archaeological site is now an Israeli national park. Kursi takes its name from the Talmudic site. A marble slab with Aramaic text discovered in December 2015 seems to indicate that the settlement had, as of c. 500 CE, a Jewish or Judeo-Christian population.

The Golan Archaeological Museum is a museum of the archaeological finds of the Golan Heights, located in Katzrin.

The exorcism of a boy possessed by a demon, or a boy with a mute spirit, is one of the miracles attributed to Jesus reported in the synoptic Gospels, involving the healing of a demonically possessed boy through exorcism. It is in all Synoptic Gospels: Mark 9:17-29, Matthew 17:14-21, Luke 9:40-44. In the Gospel narratives, this healing takes place following the Transfiguration.

Umm Qais, also known as Qays, is a town in northern Jordan principally known for its proximity to the ruins of the ancient Gadara. It is the largest city in the Bani Kinanah Department and Irbid Governorate in the extreme northwest of the country, near Jordan's borders with Israel and Syria. Today, the site is divided into three main areas: the archaeological site (Gadara), the traditional village, and the modern town of Umm Qais.

Gadara, in some texts Gedaris, was an ancient Hellenistic city in what is now Jordan, for a long time member of the Decapolis city league, a former bishopric and present Latin Catholic titular see.

Gadarene (GAD-ə-reen) may refer to:

Gadara is the name of several ancient cities from the Southern Levant, now in ruins, the best known being today in northern Jordan. Cities with the name include:

The Synagogue-Church at Gerasa in northwestern Jordan was originally an ancient Byzantine era synagogue that was later converted to a church. It is located within the Decapolis city of Gerasa and is situated on high ground that overlooks the Temple of Artemis at Gerasa. The synagogue is evidence of Jewish settlement in the Transjordan through late antiquity.

The Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities is a governmental body in Jordan responsible for the development, promotion, and preservation of the country's tourism and antiquities sectors. Established in 1967, the Ministry plays a critical role in managing Jordan's cultural heritage and promoting it as a global tourist destination. It is located at the third circle in Jabal Amman.