A definition is a statement of the meaning of a term. Definitions can be classified into two large categories: intensional definitions, and extensional definitions. Another important category of definitions is the class of ostensive definitions, which convey the meaning of a term by pointing out examples. A term may have many different senses and multiple meanings, and thus require multiple definitions.

In logic, equivocation is an informal fallacy resulting from the use of a particular word/expression in multiple senses within an argument.

A paradox is a logically self-contradictory statement or a statement that runs contrary to one's expectation. It is a statement that, despite apparently valid reasoning from true or apparently true premises, leads to a seemingly self-contradictory or a logically unacceptable conclusion. A paradox usually involves contradictory-yet-interrelated elements that exist simultaneously and persist over time. They result in "persistent contradiction between interdependent elements" leading to a lasting "unity of opposites".

In classical rhetoric and logic, begging the question or assuming the conclusion is an informal fallacy that occurs when an argument's premises assume the truth of the conclusion. Historically, begging the question refers to a fault in a dialectical argument in which the speaker assumes some premise that has not been demonstrated to be true. In modern usage, it has come to refer to an argument in which the premises assume the conclusion without supporting it. This makes it more or less synonymous with circular reasoning.

A fallacy is the use of invalid or otherwise faulty reasoning in the construction of an argument that may appear to be well-reasoned if unnoticed. The term was introduced in the Western intellectual tradition by the Aristotelian De Sophisticis Elenchis.

Deductive reasoning is the mental process of drawing valid inferences. An inference is valid if its conclusion follows logically from its premises, meaning that it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false.

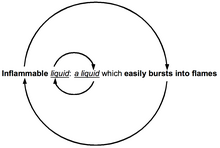

A circular definition is a type of definition that uses the term(s) being defined as part of the description or assumes that the term(s) being described are already known. There are several kinds of circular definition, and several ways of characterising the term: pragmatic, lexicographic and linguistic. Circular definitions are related to Circular reasoning in that they both involve a self-referential approach.

Circular reasoning is a logical fallacy in which the reasoner begins with what they are trying to end with. Circular reasoning is not a formal logical fallacy, but a pragmatic defect in an argument whereby the premises are just as much in need of proof or evidence as the conclusion, and as a consequence the argument fails to persuade. Other ways to express this are that there is no reason to accept the premises unless one already believes the conclusion, or that the premises provide no independent ground or evidence for the conclusion. Circular reasoning is closely related to begging the question, and in modern usage the two generally refer to the same thing.

Logical reasoning is a mental activity that aims to arrive at a conclusion in a rigorous way. It happens in the form of inferences or arguments by starting from a set of premises and reasoning to a conclusion supported by these premises. The premises and the conclusion are propositions, i.e. true or false claims about what is the case. Together, they form an argument. Logical reasoning is norm-governed in the sense that it aims to formulate correct arguments that any rational person would find convincing. The main discipline studying logical reasoning is logic.

The fallacy of four terms is the formal fallacy that occurs when a syllogism has four terms rather than the requisite three, rendering it invalid.

Informal fallacies are a type of incorrect argument in natural language. The source of the error is not just due to the form of the argument, as is the case for formal fallacies, but can also be due to their content and context. Fallacies, despite being incorrect, usually appear to be correct and thereby can seduce people into accepting and using them. These misleading appearances are often connected to various aspects of natural language, such as ambiguous or vague expressions, or the assumption of implicit premises instead of making them explicit.

In logic, the logical form of a statement is a precisely-specified semantic version of that statement in a formal system. Informally, the logical form attempts to formalize a possibly ambiguous statement into a statement with a precise, unambiguous logical interpretation with respect to a formal system. In an ideal formal language, the meaning of a logical form can be determined unambiguously from syntax alone. Logical forms are semantic, not syntactic constructs; therefore, there may be more than one string that represents the same logical form in a given language.

In logic and philosophy, a formal fallacy, deductive fallacy, logical fallacy or non sequitur is a pattern of reasoning rendered invalid by a flaw in its logical structure that can neatly be expressed in a standard logic system, for example propositional logic. It is defined as a deductive argument that is invalid. The argument itself could have true premises, but still have a false conclusion. Thus, a formal fallacy is a fallacy where deduction goes wrong, and is no longer a logical process. This may not affect the truth of the conclusion, since validity and truth are separate in formal logic.

Logic is the formal science of using reason and is considered a branch of both philosophy and mathematics and to a lesser extent computer science. Logic investigates and classifies the structure of statements and arguments, both through the study of formal systems of inference and the study of arguments in natural language. The scope of logic can therefore be very large, ranging from core topics such as the study of fallacies and paradoxes, to specialized analyses of reasoning such as probability, correct reasoning, and arguments involving causality. One of the aims of logic is to identify the correct and incorrect inferences. Logicians study the criteria for the evaluation of arguments.

Informal logic encompasses the principles of logic and logical thought outside of a formal setting. However, the precise definition of "informal logic" is a matter of some dispute. Ralph H. Johnson and J. Anthony Blair define informal logic as "a branch of logic whose task is to develop non-formal standards, criteria, procedures for the analysis, interpretation, evaluation, criticism and construction of argumentation." This definition reflects what had been implicit in their practice and what others were doing in their informal logic texts.

Philosophy of logic is the area of philosophy that studies the scope and nature of logic. It investigates the philosophical problems raised by logic, such as the presuppositions often implicitly at work in theories of logic and in their application. This involves questions about how logic is to be defined and how different logical systems are connected to each other. It includes the study of the nature of the fundamental concepts used by logic and the relation of logic to other disciplines. According to a common characterisation, philosophical logic is the part of the philosophy of logic that studies the application of logical methods to philosophical problems, often in the form of extended logical systems like modal logic. But other theorists draw the distinction between the philosophy of logic and philosophical logic differently or not at all. Metalogic is closely related to the philosophy of logic as the discipline investigating the properties of formal logical systems, like consistency and completeness.

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It studies how conclusions follow from premises due to the structure of arguments alone, independent of their topic and content. Informal logic is associated with informal fallacies, critical thinking, and argumentation theory. It examines arguments expressed in natural language while formal logic uses formal language. When used as a countable noun, the term "a logic" refers to a logical formal system that articulates a proof system. Logic plays a central role in many fields, such as philosophy, mathematics, computer science, and linguistics.

As the study of argument is of clear importance to the reasons that we hold things to be true, logic is of essential importance to rationality. Arguments may be logical if they are "conducted or assessed according to strict principles of validity", while they are rational according to the broader requirement that they are based on reason and knowledge.