Related Research Articles

Marillion are a British rock band, formed in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, in 1979. They emerged from the post-punk music scene in Britain and existed as a bridge between the styles of punk rock and classic progressive rock, becoming the most commercially successful neo-progressive rock band of the 1980s.

The threshold pledge or fund and release system is a way of making a fundraising pledge as a group of individuals, often involving charitable goals or financing the provision of a public good. An amount of money is set as the goal or threshold to reach for the specified purpose and interested individuals will pitch in, but the money at first either remains with the pledgers or is held in escrow.

ArtistShare is the internet's first commercial crowdfunding website. It also operates as a record label and business model for artists which enables them to fund their projects by allowing the general public to directly finance, watch the creative process, and in most cases gain access to extra material from an artist. According to Bloomberg News, the company's chief executive officer, Brian Camelio, founded ArtistShare in 2000 with the idea that fans would finance production costs for albums sold only on the Internet and Artists also would enjoy much more favourable contract terms. ArtistShare was described in 2005 as a "completely new business model for creative artists" which "benefits both the artist and the fans by financing new and original artistic projects while building a strong and loyal fan base".

Electric Eel Shock (EES) are a three-piece garage rock band, formed in Tokyo in 1994. They first toured the United States in 1999.

Sellaband was a music website that allowed artists to raise the money from their fans and the SellaBand community in order to record a professional album. Sellaband used the mechanisms of crowdfunding and was to be seen as a Direct-to-Fan/fan-funded music platform utilising a Threshold Pledge System / Provision Point Mechanism. It was set up by Johan Vosmeijer, Pim Betist, and Dagmar Heijmans in August 2006. Its offices used to be located in Amsterdam, Netherlands, but it was originally incorporated in Bocholt, Germany.

Julia Nunes is an American singer-songwriter from Fairport, New York. Her career has progressed online through her videos of pop songs on YouTube, in which she sings harmony with herself and plays acoustic instruments, primarily the ukulele, guitar, melodica, and piano.

Kickstarter is an American public benefit corporation based in Brooklyn, New York, that maintains a global crowdfunding platform focused on creativity. The company's stated mission is to "help bring creative projects to life". As of July 2021, Kickstarter has received nearly $6 billion in pledges from 20 million backers to fund 205,000 projects, such as films, music, stage shows, comics, journalism, video games, technology, publishing, and food-related projects.

PledgeMusic was an online direct-to-fan music platform, launched in August 2009. It was started to facilitate musicians looking to pre-sell, market, and distribute projects; such as recordings and concerts. It bore similarities to other artist payment platforms as ArtistShare, Kickstarter, Indiegogo, Patreon, RocketHub and Sellaband.

Language Room is an American indie/alternative rock band based in Austin, Texas. Its members are Todd Sapio, Scott Graham, Matt Graham, and Sean Hill (drums). In 2014 the band changed its name to KIONA.

RocketHub was an online crowdfunding platform launched in 2010, its first use was September 1, 2009. Based in New York City, its users—including musicians, entrepreneurs, scientists, game developers, philanthropists, filmmakers, photographers, theatre producers/directors, writers, and fashion designers,—posted fundraising campaigns to it to raise funds and awareness for projects and endeavors. Operating in over 190 different countries, RocketHub was once considered one of America's largest crowdfunding platforms.

Indiegogo is an American crowdfunding website founded in 2008 by Danae Ringelmann, Slava Rubin, and Eric Schell. Its headquarters are in San Francisco, California. The site is one of the first sites to offer crowd funding. Indiegogo allows people to solicit funds for an idea, charity, or start-up business. Indiegogo charges a 5% fee on contributions. This charge is in addition to Stripe credit card processing charges of 3% + $0.30 per transaction. Fifteen million people visit the site each month.

Zequs.com is an online crowd funding platform that operates in an 'All or Nothing' method for individuals or groups to raise funds for creative projects. The site utilises social networks, with the use of social media, to help promote current projects. There are no restrictions from where those looking for funding are based. The head office is located in Queens Club, London.

Theatre Is Evil is the second studio album by Amanda Palmer, and first with her band The Grand Theft Orchestra. It was released on September 7, 2012 in Australia, on September 10, 2012 in the United Kingdom and Europe, and September 11, 2012 in the United States and Canada. The album has been released by Palmer's own record label, 8 Ft. Records, with distribution handled by Cooking Vinyl in the UK and Europe, and Alliance Entertainment in the US.

Video game development has typically been funded by large publishing companies or are alternatively paid for mostly by the developers themselves as independent titles. Other funding may come from government incentives or from private funding.

InvestedIn is a crowd funding website for fund raising projects and charity events such as walkathons and celebrity cause-based campaigns. InvestedIn is also a technology provider offering a white label crowdfunding platform for commercial and non-profit use.

Experiment, formerly called Microryza, is a US website for crowdfunding science-based research projects. Researchers can post their research projects to solicit pledges. Experiment works on the all-or-nothing funding model. The backers are only charged if the research projects reach their funding target during a set time frame. In February 2014, the site changed its name from Microryza to Experiment.com.

Crowdfunding is the practice of funding a project or venture by raising small amounts of money from a large number of people, in modern times typically via the Internet. Crowdfunding is a form of crowdsourcing and alternative finance. In 2015, over US$34 billion were raised worldwide by crowdfunding.

MusicBee is a crowdfunding platform focused on independent music based in Hong Kong. The company stated its mission as to gather resources and help bring independent music projects into life, providing musicians with dreams and opportunities. MusicBee has reportedly received $2 million funding over 15 music project within one year.

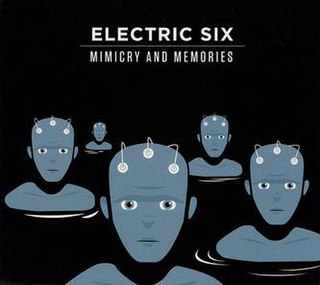

Mimicry and Memories is a compilation album by Electric Six. Disc one, Mimicry, is composed of cover songs. Disc two, Memories, consists of demos, B-sides and rarities. It was funded through a Kickstarter campaign and self-released directly to the campaign's backers.

References

- ↑ Van Buskirk, Eliot (10 March 2008). "SlicethePie Unleashes Its First Fan-Funded Album". Wired .

- ↑ Chaney, D. (2010). "What future for fan-funded labels in the music recording industry? The cases of MyMajorCompany and ArtistShare". International Journal of Arts Management. 12 (2): 44-48.

- ↑ "Can You Spare a Quarter? Crowdfunding Sites Turn Fans into Patrons of the Arts". Wharton Innovation and Entrepreneurship. 8 December 2010. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ↑ "About Us". ArtistShare. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ↑ "Learn More". Indiegogo. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ↑ Needleman, Sarah (1 November 2011). "When 'Friending' Becomes a Source of Start-Up Funds". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ↑ "about". PledgeMusic. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ↑ "FAQ". PledgeMusic. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ↑ Ostrow, Jonathan (16 August 2010). "Musician's guide to Fan-Funded Music". Music Think Tank. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ↑ "How it Works -- Artists". Sellaband. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ↑ "Join SellaBand". SellaBand. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- 1 2 Masters, Tim (11 May 2001). "Marillion fans to the rescue". BBC News.

- 1 2 Petridis, Alexis (18 April 2008). "This song was brought to you by ..." The Guardian . Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ↑ The Marillion story and what we can all learn from it - Music 4.5 Archived 9 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Amanda Palmer: The new Record, Art Book, and Tour". Kickstarter.

- ↑ Sisario, Ben (5 June 2012). "Amanda Palmer Takes Connecting With Her Fans to a New Level". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Ellis Paul". Ellis Paul. 9 July 2008.

- ↑ "Musicians and fans join together to get albums made". The Boston Globe .

- ↑ "Ellis Paul". Ellis Paul. 26 September 2012.

- ↑ "Wanna Go VIP? Electric Eel Shock'll show you the way..." DrownedInSound. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ Lindvall, Helienne (21 January 2010). "Behind the music: The fan-funded model that led to a major record deal". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "How fan-funding is changing the face of music finance". BBC News. 12 July 2012.

- ↑ Gareth McLean (13 August 2001). "In the realm of pretences". The Guardian. UK.

- ↑ "An Argument Against Fan Funding". Music Think Tank.

- ↑ "The Problem With Fan-Funded Music". NME .

- ↑ Sofge, Erik (18 August 2012). "The Good, the Bad and the Crowdfunded". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ "How Much Does Crowd Funding Cost Musicians?". NPR. 23 November 2012.

- ↑ "Music Clout". musicclout.com.