Examples

As a result, the earliest stories in the genre date to the end of the 19th century, and include W.H. Hudson's A Crystal Age (1887) and H.G. Wells' The Time Machine (1895). [1] Classic examples of the genre from the first half of the 20th century include Olaf Stapledon's Last and First Men (1930) and Arthur C. Clarke's Against the Fall of Night (1948). [1] [2] Later examples include Brian Aldiss' The Long Afternoon of Earth (1962), Michael Moorcock's Dancers at the End of Time series (1972–1976), Stephen Baxter's Xeelee Sequence series (1986–), Paul J. McAuley's Confluence trilogy (1997–1999) and Alastair Reynolds's Revelation Space series (2000–), as well as numerous works by Robert Silverberg, Doris Piserchia and Michael G. Coney. [1] [2] [3]

The far future fantasy subgenre begun with Clark Ashton Smith's Zothique stories (representing the far future fantasy subgenre), with the first work in the series published in 1932, with other influential authors here being Jack Vance ( Dying Earth , 1950) Damian Broderick ( Sorcerer's World , 1970) and Gene Wolfe ( The Book of the New Sun , 1980). [2] [3]

Short stories about far future have been collected in a number of anthologies, such as Far Futures (1997) and One Million AD (2006). [1]

Themes

The concept of the far future is hard to define precisely, but a common element of such stories is to show the society that is "so completely transformed from the present day as to be almost unrecognizable". [2] George Mann noted that the common themes in far future works are those of "entropy and dissolution". [3]

Future of human evolution is considered a classic theme, harkening to H.G. Wells' The Time Machine and its division of the human race into two subspecies, the Eloi and the Morlocks. Many later works build on this idea, exploring futures in which humans themselves evolve into post-material forms of energy or software, and this theme. [2] [3] [4]

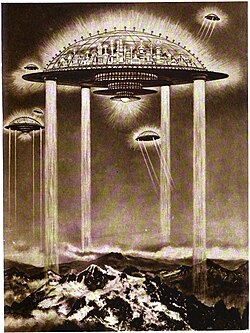

Another recurring theme is the post-apocalyptic one, related to the Dying Earth genre, or the suppression of humanity by more powerful beings, such as robots, artificial intelligences, technologically advanced aliens, or god-like beings of pure energy. [1] [2] [3] Where humanity is not being eradicated, space travel and time travel themes also make relatively frequent appearances, as tools of sufficiently advanced, future civilizations; the former theme also marks an overlap with the more epic works of the space opera genre. [1]

Some writers attempt to outline a future history of mankind or even the universe, with one of the first works attempting this being Olaf Stapledon, whose 1930 classic work was entitled Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future. [3]

Sometimes the far future genre moves from science fiction to fantasy, showing a society where civilization has regressed to the point where older technologies are no longer understood and are seen as magic. This subgenre is sometimes known as the "far future fantasy" [2] and partially overlaps with the science fantasy genre. [3] At the same time, the relics of a technological past "protruding into a more primitive... landscape", a theme known as the "Ruined earth", have been described as "among the most potent of SF's icons". [5]

Dutch historian and sociologist Fred Polak distinguished between two categories of works about the future, "future of prophecy" and "future of destiny". The former is concerned about the present and uses the future as an opportunity to warn about the dangers of the present that should be avoided, often touching upon dystopian themes. The latter category is broader and concerned more with exploring philosophical themes such as Utopias, eschatology or the ultimate fate of the universe. [1]

George Mann observed that this genre has produced "many excellent allegorical or moral tales". [3] Russell Blackford concurred with this sentiment, however also noted that "some critics" have pointed to "essential conservatism" and "lack of social relevance" in far future narratives, as contrasted with near future ones, and those realistic predictions of far future are impossible, as humanity in the far future if it exists, is likely to be beyond our comprehension. [2]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.