Child custody, conservatorship and guardianship describe the legal and practical relationship between a parent and the parent's child, such as the right of the parent to make decisions for the child, and the parent's duty to care for the child.

Child support is an ongoing, periodic payment made by a parent for the financial benefit of a child following the end of a marriage or other similar relationship. Child maintenance is paid directly or indirectly by an obligor to an obligee for the care and support of children of a relationship that has been terminated, or in some cases never existed. Often the obligor is a non-custodial parent. The obligee is typically a custodial parent, a caregiver, or a guardian.

The fathers' rights movement is a social movement whose members are primarily interested in issues related to family law, including child custody and child support, that affect fathers and their children. Many of its members are fathers who desire to share the parenting of their children equally with their children's mothers—either after divorce or marital separation. The movement includes men as well as women, often the second wives of divorced fathers or other family members of men who have had some engagement with family law. Most Fathers' rights advocates argue for formal gender equality.

Robert Bruce McClelland is an Australian judge and former politician who has served on the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia since 2015, including as Deputy Chief Justice of that court since 2018. He was previously Attorney-General of Australia from 2007 to 2011, and a member of the House of Representatives from 1996 to 2013, representing the Labor Party.

Child custody is a legal term regarding guardianship which is used to describe the legal and practical relationship between a parent or guardian and a child in that person's care. Child custody consists of legal custody, which is the right to make decisions about the child, and physical custody, which is the right and duty to house, provide and care for the child. Married parents normally have joint legal and physical custody of their children. Decisions about child custody typically arise in proceedings involving divorce, annulment, separation, adoption or parental death. In most jurisdictions child custody is determined in accordance with the best interests of the child standard.

Australian family law is principally found in the federal Family Law Act 1975 and the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia Rules 2021 as well as in other laws and the common law and laws of equity, which affect the family and the relationship between those people, including when those relationships end. Most family law is practised in the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia and the Family Court of Western Australia. Australia recognises marriages entered into overseas as well as divorces obtained overseas if they were effected in accordance with the laws of that country. Australian marriage and "matrimonial causes" are recognised by sections 51(xxi) and (xxii) of the Constitution of Australia and internationally by marriage law and conventions, such as the Hague Convention on Marriages (1978).

In family law, contact, visitation and access are synonym terms that denotes the time that a child spends with the noncustodial parent, according to an agreed or court specified parenting schedule. The visitation term is not used in a shared parenting arrangement where both parents have joint physical custody.

The Family Law Act 1975(Cth) is an Act of the Parliament of Australia. It has 15 parts and is the primary piece of legislation dealing with divorce, parenting arrangements between separated parents (whether married or not), property separation, and financial maintenance involving children or divorced or separated de facto partners: in Australia. It also covers family violence. It came into effect on 5 January 1976, repealing the Matrimonial Causes Act 1961, which had been largely based on fault. On the first day of its enactment, 200 applications for divorce were filed in the Melbourne registry office of the Family Court of Australia, and 80 were filed in Adelaide, while only 32 were filed in Sydney.

In the United States, child support is the ongoing obligation for a periodic payment made directly or indirectly by an "obligor" to an "obligee" for the financial care and support of children of a relationship or a marriage. The laws governing this kind of obligation vary dramatically state-by-state and tribe-by-tribe among Native Americans. Each individual state and federally recognized tribe is responsible for developing its own guidelines for determining child support.

The fathers' rights movement in the United States is a group that provides fathers with education, support and advocacy on family law issues of child custody, access, child support, domestic violence and child abuse. Members protest what they see as evidence of gender bias against fathers in the branches and departments of various governments, including the family courts.

The fathers' rights movement has simultaneously evolved in many countries, advocating for shared parenting after divorce or separation, and the right of children and fathers to have close and meaningful relationships. This article provides details about the fathers' rights movement in specific countries.

The Non-Custodial Parents Party was a minor political party in Australia registered between 1999 and 2020. It supported less government control of many aspects of daily family life, focusing on reform of family law and child support.

The No Goods and Services Tax Party, previously the Abolish Child Support and Family Court Party, was a minor Australian political party registered between 1997 and 2006 which fielded candidates between the 1998 and 2004 federal elections. The change of name in 2001 was largely a response to the Howard Government's implementation of the Goods and Services Tax. It polled low totals. One Nation founder David Ettridge contested the Senate in Queensland in 2001 for the party.

The men's rights movement in India is composed of various independent men's rights organisations in India. Proponents of the movement support the introduction of gender-neutral legislation and repeal of laws that are biased against men.

The Equal Parenting Alliance is a minor political party in the United Kingdom. Founded in February 2006, it aims to bring about reform of the Family law system in England and Wales. It was started by former members of Real Fathers 4 Justice, a father's rights organisation, and a similar group New Fathers 4 Justice. Its leader is Ray Barry.

A noncustodial parent is a parent who does not have physical custody of his or her minor child as the result of a court order. When the child lives with only one parent, in a sole custody arrangement, then the parent with which the child lives is the custodial parent while the other parent is the non-custodial parent. The non-custodial parent may have contact or visitation rights. In a shared parenting arrangement, where the child lives an equal or approximately equal amount of time with the mother and father, both are custodial parents and neither is a non-custodial parent.

Law in Australia with regard to children is often based on what is considered to be in the best interest of the child. The traditional and often used assumption is that children need both a mother and a father, which plays an important role in divorce and custodial proceedings, and has carried over into adoption and fertility procedures. As of April 2018 all Australian states and territories allow adoption by same-sex couples.

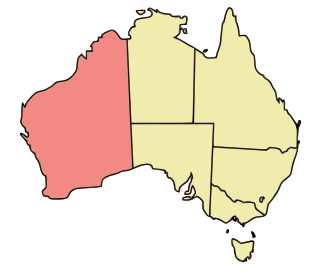

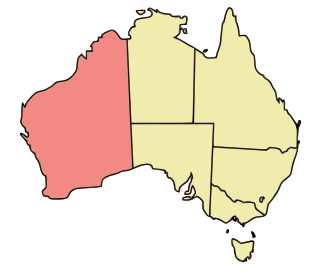

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBTQ) rights in Western Australia have seen significant progress since the beginning of the 21st century, with male sex acts legal since 1990 and the state parliament passing comprehensive law reforms in 2002. The state was the first place within Australia to grant full adoption rights to same-sex couples in 2002. As of 2024, Western Australia is the only place within Australia to ban altrustic surrogacy for same-sex couples and also the only mainland state to still legally allows conversion therapy practices.

The Family Law Legislation Amendment Act 2011 is an Act of the Australian Parliament that amends the Family Law Act 1975. It has four parts and its main amendments involve how courts define and respond to allegations of child abuse and domestic violence.

Australian Better Families (ABF) is an Australian political party registered on 31 August 2018. The Party's founder is Leith Erikson and has the slogan “Better Families for a Better Australia”. Australian Better Families campaign targets new and existing laws in the areas of mental health, child support and family law. Australian Better Families promotes the rights of father's in the legal system, particularly stressing the trauma caused by separation from family during legal proceedings. The party is a branch of the Australian Brotherhood of Fathers organisation, who stated they created the party as they "can no longer sit silently on the political sidelines to witness the betrayal of our children and families."