The Catalan Countries are those territories where the Catalan language is spoken. They include the Spanish regions of Catalonia, the Balearic Islands, Valencian Community, and parts of Aragon and Murcia (Carche), as well as the Principality of Andorra, the department of Pyrénées-Orientales in France, and the city of Alghero in Sardinia (Italy). It is often used as a sociolinguistic term to describe the cultural-linguistic area where Catalan is spoken. In the context of Catalan nationalism, the term is sometimes used in a more restricted way to refer to just Catalonia, Valencia and the Balearic Islands. The Catalan Countries do not correspond to any present or past political or administrative unit, though most of the area belonged to the Crown of Aragon in the Middle Ages. Parts of Valencia (Spanish) and Catalonia (Occitan) are not Catalan-speaking.

The Galician People's Party was a Galician political party in the first years of the Spanish democracy.

The Irmandades da Fala was a Galician nationalist organization active between 1916 and 1936. It was the first political organization of Galicia that used only the Galician language.

The Partido Galeguista was a Galician nationalist party founded in December 1931. It achieved notoriety during the time of the Spanish Second Republic. The PG grouped a number of historical Galician intellectuals, and was fundamental in the elaboration of the Galician Statute of Autonomy.

Valentí Almirall i Llozer was a Catalan politician, considered one of the fathers of modern Catalan nationalism, and more specifically, of the left-wing variety.

Nationalist Left was a Galician political party formed in 1992. The party had about 600 members in 2002. EN was part of the Galician Nationalist Bloc (BNG) from its foundation to February 2012. On 14 April 2012 the organization was dissolved and its members joined the Máis Galiza party.

The Galician Nationalist Party–Galicianist Party was a Galician nationalist and liberal political party, coming from a split of the Galician Coalition. The PNG–PG had 132 members in 2002. Xosé Mosquera Casero was the last secretary general, after the VIII Congress in September 2011. The party merged with Commitment to Galicia in 2012.

Galician Solidarity was a Galician regionalist political organization active between 1907 and 1912.

Galician Coalition is a political party in Galicia, Spain with a Galician nationalist and centrist ideology. Since 2012 CG is part of the coalition Compromiso por Galicia.

The Republican Nationalist Party of Ourense was a Galician nationalist party founded in late 1930 based in the province of Ourense. The main leaders of the party were Ramón Otero Pedrayo, Xaquín Lorenzo Fernández, Florentino López Cuevillas and Vicente Risco.

The Catalan Republic was a state proclaimed in 1931 by Francesc Macià as the "Catalan Republic within the Iberian Federation", in the context of the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic. It was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, and superseded three days later, on 17 April, by the Generalitat de Catalunya, the Catalan institution of self-government within the Spanish Republic.

The Catalan State was a short-lived state that existed in Catalonia from 6 to 7 October 1934 during the Events of 6 October. The Catalan State was proclaimed by Lluís Companys, the left-wing President of the Generalitat of Catalonia, as a state "within the Spanish Federal Republic" in response to members of the right-wing CEDA party being included in the government of Second Spanish Republic. The Catalan State was immediately suppressed by the Spanish Army led by General Domènec Batet and Companys surrendered the next day.

The People's Army of Catalonia was an army created by the Generalitat of Catalonia on 6 December 1936, during the Spanish Civil War. Its existence was more theoretical than real, because the original structure of the popular militias continued to exist despite the efforts of the Generalitat. After the May Days it was dissolved and its structure assumed by the Spanish Republican Army, which definitively militarized the militias of Catalonia and Aragon.

The Crop Contracts Law was a law passed by the Parliament of Catalonia on 21 March 1934, and enacted on the symbolic date of 14 April 1934. The basic purpose of the law was to protect the tenant farmers from the Rabassa Morta, a special type of land leasing for vineyards in Catalonia, and promote their access to the land they were cultivating. The Crop Contracts Law was not implemented because it was revoked by the Court of Constitutional Guarantees of the Spanish Government. The negotiation that followed between the Spanish and Catalan governments was interrupted by the Events of 6 October, the proclamation of the Catalan State, and the arrest of Catalan President Lluís Companys.

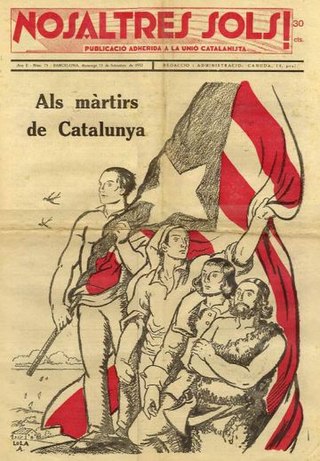

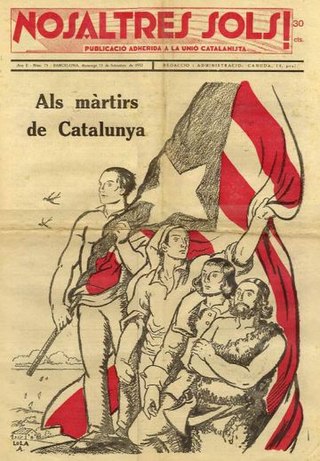

Nosaltres Sols! was a Catalan nationalist paramilitary political movement from the 20th century. It was born in 1931, in a rented space property of the political party Unió Catalanistaand created a weekly journal with the exact same name as well. The purpose of the organization was to confront those who were considered enemies of Catalonia, mainly Spanish unionists, but also anarchists, communists and fascists.

Javier Moreno Luzón is a Spanish historian, professor of the History of Thought and Social and Political Movements at the Complutense University of Madrid. He is an expert in the political history of Restoration Spain.

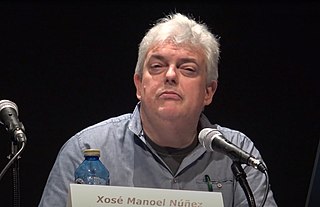

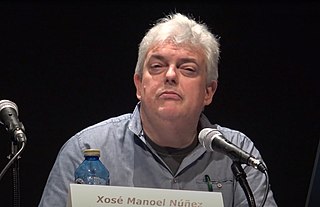

Xosé Manoel Núñez Seixas is a Spanish historian who specializes in nationalism studies, the cultural history of war and violence, and migration studies.

The Assembly of Catalonia was a unitary body of the anti-Francoist opposition of Catalonia created in November 1971. Its fundamental demands were the demand for democratic freedoms, the general amnesty for political prisoners and the achievement of the statute of autonomy, which were synthesized in the motto of Freedom, Amnesty, Statute of Autonomy. In addition to the political parties—all of them clandestine—forces of various kinds were part of it, such as trade union organizations, professional groups, representatives of the university movement, neighborhood movements, Christian groups, regional assemblies, etc. The objectives of the Assembly were achieved during the democratic transition, especially when the Cortes approved the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia in 1979.

The Autonomous Region of Catalonia was established after the grant of self-government to Catalonia during the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939), becoming an autonomous region within the Spanish Republic. The Generalitat of Catalonia was the institution in which the autonomous government of Catalonia was organized, it was established in order to replace the Catalan Republic proclaimed during the events of the proclamation of the Spanish Republic.

The Bases for the Catalan Regional Constitution, better known as the Manresa Bases, is the document presented as a draft Catalan regional constitution for a paper by the Unió Catalanista to the council of representatives of Catalanist associations, which met in Manresa (Barcelona) on 25 and 27 March 1892 at the initiative of the Lliga de Catalunya. The Bases de Manresa are often considered to be the "birth certificate of political Catalanism", at least that of conservative roots.