The Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution provides the procedure for electing the president and vice president. It replaced the procedure provided in Article II, Section 1, Clause 3, by which the Electoral College originally functioned. The amendment was proposed by the Congress on December 9, 1803, and was ratified by the requisite three-fourths of state legislatures on June 15, 1804. The new rules took effect for the 1804 presidential election and have governed all subsequent presidential elections.

The 1788–1789 United States presidential election was the first quadrennial presidential election. It was held from Monday, December 15, 1788, to Saturday, January 10, 1789, under the new Constitution ratified that same year. George Washington was unanimously elected for the first of his two terms as president and John Adams became the first vice president. This was the only U.S. presidential election that spanned two calendar years without a contingent election and the first national presidential election in American history.

The 1792 United States presidential election was the second quadrennial presidential election. It was held from Friday, November 2, to Wednesday, December 5, 1792. Incumbent President George Washington was elected to a second term by a unanimous vote in the electoral college, while John Adams was re-elected as vice president. Washington was essentially unopposed, but Adams faced a competitive re-election against Governor George Clinton of New York.

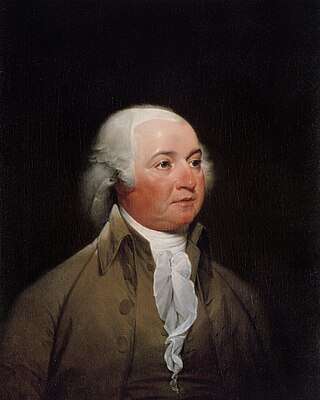

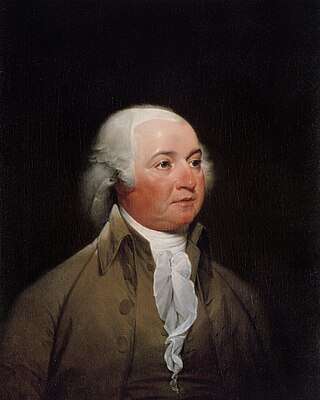

The 1796 United States presidential election was the third quadrennial presidential election of the United States. It was held from Friday, November 4 to Wednesday, December 7, 1796. It was the first contested American presidential election, the first presidential election in which political parties played a dominant role, and the only presidential election in which a president and vice president were elected from opposing tickets. Incumbent Vice President John Adams of the Federalist Party defeated former Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson of the Democratic-Republican Party.

The 1800 United States presidential election was the fourth quadrennial presidential election. It was held from October 31 to December 3, 1800. In what is sometimes called the "Revolution of 1800", the Democratic-Republican candidate, Vice President Thomas Jefferson, defeated the Federalist Party candidate, incumbent president John Adams. The election was a political realignment that ushered in a generation of Democratic-Republican leadership.

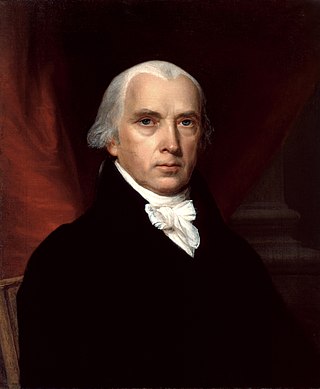

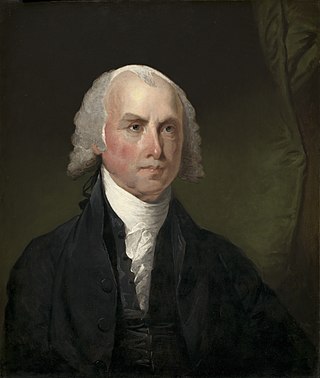

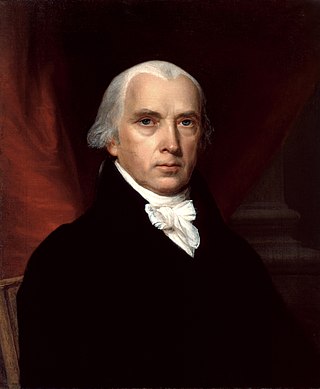

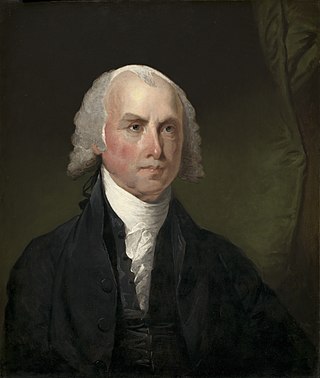

The 1812 United States presidential election was the seventh quadrennial presidential election. It was held from Friday, October 30, 1812 to Wednesday, December 2, 1812. Taking place in the shadow of the War of 1812, incumbent Democratic-Republican President James Madison defeated DeWitt Clinton, who drew support from dissident Democratic-Republicans in the North as well as Federalists. It was the first presidential election to be held during a major war involving the United States.

The 1816 United States presidential election was the eighth quadrennial presidential election. It was held from November 1 to December 4, 1816. In the first election following the end of the War of 1812, Democratic-Republican candidate James Monroe defeated Federalist Rufus King. The election was the last in which the Federalist Party fielded a presidential candidate.

The 1820 United States presidential election was the ninth quadrennial presidential election. It was held from Wednesday, November 1, to Wednesday, December 6, 1820. Taking place at the height of the Era of Good Feelings, the election saw incumbent Democratic-Republican President James Monroe win re-election without a major opponent. It was the third and the most recent United States presidential election in which a presidential candidate ran effectively unopposed. As of 2022, this is the most recent presidential election where an incumbent president was re-elected who was neither a Democrat nor a Republican, before the Democratic-Republican party split into separate parties.

The Federalist Papers is a collection of 85 articles and essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the collective pseudonym "Publius" to promote the ratification of the Constitution of the United States. The collection was commonly known as The Federalist until the name The Federalist Papers emerged in the 20th century.

An electoral college is a set of electors who are selected to elect a candidate to particular offices. Often these represent different organizations, political parties or entities, with each organization, political party or entity represented by a particular number of electors or with votes weighted in a particular way.

The United States Electoral College is the group of presidential electors required by the Constitution to form every four years for the sole purpose of appointing the president and vice president. Each state and the District of Columbia appoints electors pursuant to the methods described by its legislature, equal in number to its congressional delegation. Federal office holders, including senators and representatives, cannot be electors. Of the current 538 electors, an absolute majority of 270 or more electoral votes is required to elect the president and vice president. If no candidate achieves an absolute majority there, a contingent election is held by the House of Representatives to elect the president and by the Senate to elect the vice president.

George Clinton was an American soldier, statesman, and Founding Father of the United States. A prominent Democratic-Republican, Clinton served as the fourth vice president of the United States from 1805 until his death in 1812. He also served as the first Governor of New York from 1777 to 1795 and again from 1801 to 1804. Along with John C. Calhoun, he is one of two vice presidents to hold office under two consecutive presidents.

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. Although the convention was intended to revise the league of states and first system of government under the Articles of Confederation, the intention from the outset of many of its proponents, chief among them James Madison of Virginia and Alexander Hamilton of New York, was to create a new Frame of Government rather than fix the existing one. The delegates elected George Washington of Virginia, former commanding general of the Continental Army in the late American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) and proponent of a stronger national government, to become President of the convention. The result of the convention was the creation of the Constitution of the United States, placing the Convention among the most significant events in American history.

Federalist No. 52, an essay by James Madison or Alexander Hamilton, is the fifty-second essay out of eighty-five making up The Federalist Papers, a collection of essays written during the Constitution's ratification process, most of them written either by Hamilton or Madison. It was published in the New York Packet on February 8, 1788, with the pseudonym Publius, under which all The Federalist papers were published. This essay is the first of two examining the structure of the United States House of Representatives under the proposed United States Constitution. It is titled The House of Representatives".

Federalist No. 66 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the sixty-sixth of The Federalist Papers. It was published on March 8, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. The title is "Objections to the Power of the Senate To Set as a Court for Impeachments Further Considered".

Federalist No. 76, written by Alexander Hamilton, was published on April 1, 1788. The Federalist Papers are a series of eighty-five essays written to urge the ratification of the United States Constitution. These letters were written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the name of Publius in the late 1780s. This paper discusses the arrangement of the power of appointment and the system of checks and balances. The title is "The Appointing Power of the Executive", and is the tenth in a series of 11 essays discussing the powers and limitations of the Executive branch. There are three options for entrusting power: a single individual, a select congregation, or an individual with the unanimity of the assembly. Hamilton supported bestowing the president with the nominating power but the ratifying power would be granted to the senate in order to have a process with the least bias.

The drafting of the Constitution of the United States began on May 25, 1787, when the Constitutional Convention met for the first time with a quorum at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to revise the Articles of Confederation. It ended on September 17, 1787, the day the Frame of Government drafted by the convention's delegates to replace the Articles was adopted and signed. The ratification process for the Constitution began that day, and ended when the final state, Rhode Island, ratified it on May 29, 1790.

The election of the president and the vice president of the United States is an indirect election in which citizens of the United States who are registered to vote in one of the fifty U.S. states or in Washington, D.C., cast ballots not directly for those offices, but instead for members of the Electoral College. These electors then cast direct votes, known as electoral votes, for president, and for vice president. The candidate who receives an absolute majority of electoral votes is then elected to that office. If no candidate receives an absolute majority of the votes for president, the House of Representatives elects the president; likewise if no one receives an absolute majority of the votes for vice president, then the Senate elects the vice president.

The United States elections of 1788–1789 were the first federal elections in the United States following the ratification of the United States Constitution in 1788. In the elections, George Washington was elected as the first president and the members of the 1st United States Congress were selected.

In the United States, a contingent election is used to elect the president or vice president if no candidate receives a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed. A presidential contingent election is decided by a special vote of the United States House of Representatives, while a vice-presidential contingent election is decided by a vote of the United States Senate. During a contingent election in the House, each state delegation votes en bloc to choose the president instead of representatives voting individually. Senators, by contrast, cast votes individually for vice president.