The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces.

Article One of the Constitution of the United States establishes the legislative branch of the federal government, the United States Congress. Under Article One, Congress is a bicameral legislature consisting of the House of Representatives and the Senate. Article One grants Congress various enumerated powers and the ability to pass laws "necessary and proper" to carry out those powers. Article One also establishes the procedures for passing a bill and places various limits on the powers of Congress and the states from abusing their powers.

Article Two of the United States Constitution establishes the executive branch of the federal government, which carries out and enforces federal laws. Article Two vests the power of the executive branch in the office of the president of the United States, lays out the procedures for electing and removing the president, and establishes the president's powers and responsibilities.

The federal government of the United States is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, five major self-governing territories, several island possessions, and the federal district/national capital of Washington, D.C., where most of the federal government is based.

Separation of powers is a political doctrine originating in the writings of Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu in The Spirit of the Laws, in which he argued for a constitutional government with three separate branches, each of which would have defined abilities to check the powers of the others. This philosophy heavily influenced the drafting of the United States Constitution, according to which the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial branches of the United States government are kept distinct in order to prevent abuse of power. The American form of separation of powers is associated with a system of checks and balances.

The powers of the president of the United States include those explicitly granted by Article II of the United States Constitution as well as those granted by Acts of Congress, implied powers, and also a great deal of soft power that is attached to the presidency.

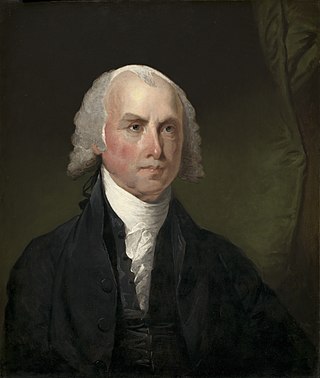

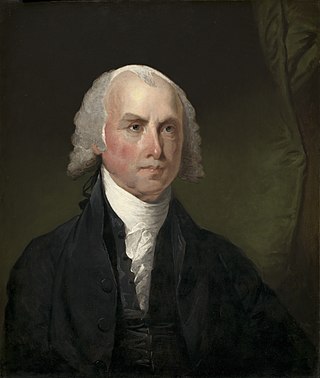

Federalist No. 47 is the forty-seventh paper from The Federalist Papers. It was first published by The New York Packet on January 30, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist Papers were published, but its actual author was James Madison. This paper examines the separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government under the proposed United States Constitution due to the confusion of the concept at the citizen level. It is titled "The Particular Structure of the New Government and the Distribution of Power Among Its Different Parts".

Federalist No. 66 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the sixty-sixth of The Federalist Papers. It was published on March 8, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. The title is "Objections to the Power of the Senate To Set as a Court for Impeachments Further Considered".

Federalist No. 67 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the sixty-seventh of The Federalist Papers. This essay's title is "The Executive Department" and begins a series of eleven separate papers discussing the powers and limitations of that branch. Federalist No. 67 was published under the pseudonym Publius, like the rest of the Federalist Papers. It was published in the New York Packet on Tuesday, March 11, 1788.

Federalist No. 68 is the 68th essay of The Federalist Papers, and was published on March 12, 1788. It was probably written by Alexander Hamilton under the pseudonym "Publius", the name under which all of the Federalist Papers were published. Since all of them were written under this pseudonym, who wrote what cannot be verified with certainty. Titled "The Mode of Electing the President", No. 68 describes a perspective on the process selecting the chief executive of the United States. In this essay, the author sought to convince the people of New York of the merits of the proposed constitution. Number 68 is the second in a series of 11 essays discussing the powers and limitations of the executive branch and the only one to describe the method of selecting the president.

Federalist No. 70, titled "The Executive Department Further Considered", is an essay written by Alexander Hamilton arguing for a single, robust executive provided for in the United States Constitution. It was originally published on March 15, 1788, in The New York Packet under the pseudonym Publius as part of The Federalist Papers and as the fourth in Hamilton's series of eleven essays discussing executive power.

Federalist No. 71 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the seventy-first of The Federalist Papers. It was published on March 18, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. Its title is "The Duration in Office of the Executive", and it is the fifth in a series of 11 essays discussing the powers and limitations of the executive branch.

Federalist No. 73 is an essay by the 18th-century American statesman Alexander Hamilton. It is the seventy-third of The Federalist Papers, a collection of articles written to promote the ratification of the United States Constitution. It was published on March 21, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. Its title is "The Provision For The Support of the Executive, and the Veto Power", and it is the seventh in a series of 11 essays discussing the powers and limitations of the Executive branch of the United States government.

Federalist No. 74 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the seventy-fourth of The Federalist Papers. It was published on March 25, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. Its title is "The Command of the Military and Naval Forces, and the Pardoning Power of the Executive", and it is the eighth in a series of 11 essays discussing the powers and limitations of the Executive branch.

Federalist No. 75 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton and seventy-fifth in the series of The Federalist Papers. It was published on March 26, 1788 under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. Its title is "The Treaty Making Power of the Executive", and it is the ninth in a series of 11 essays discussing the powers and limitations of the Executive branch.

Federalist No. 77 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the seventy-seventh of The Federalist Papers. It was published on April 2, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. The title is "The Appointing Power Continued and Other Powers of the Executive Considered", and it is the last in a series of 11 essays discussing the powers and limitations of the Executive Branch.

The unitary executive theory is a controversial legal theory in United States constitutional law which holds that the president of the United States possesses the power to control the entire federal executive branch.

A plenary power or plenary authority is a complete and absolute power to take action on a particular issue, with no limitations. It is derived from the Latin term plenus, 'full'.

The U.S. Congress in relation to the president and Supreme Court has the role of chief legislative body of the United States. However, the Founding Fathers of the United States built a system in which three powerful branches of the government, using a series of checks and balances, could limit each other's power. As a result, it helps to understand how the United States Congress interacts with the presidency as well as the Supreme Court to understand how it operates as a group.

The president of the United States is authorized by the U.S. Constitution to grant a pardon for a federal crime. The other forms of the clemency power of the president are commutation of sentence, remission of fine or restitution, and reprieve. A person may decide not to accept a pardon, in which case it does not take effect, according to a Supreme Court majority opinion in Burdick v. United States. In 2021, the 10th Circuit ruled that acceptance of a pardon does not constitute a legal confession of guilt, recognizing the Supreme Court's earlier language as authoritative.