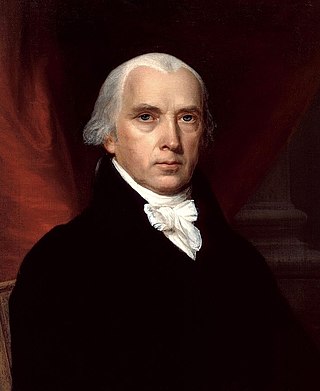

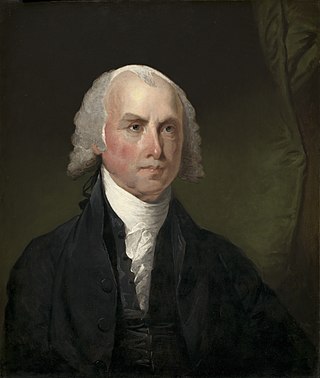

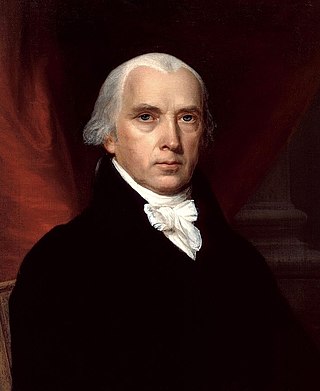

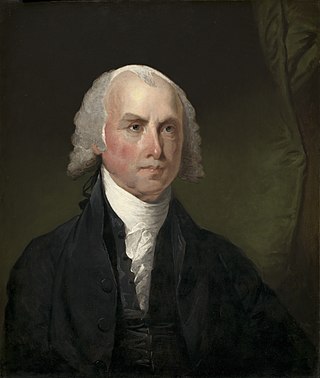

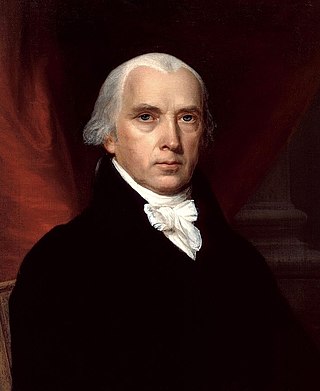

James Madison was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed the "Father of the Constitution" for his pivotal role in drafting and promoting the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights.

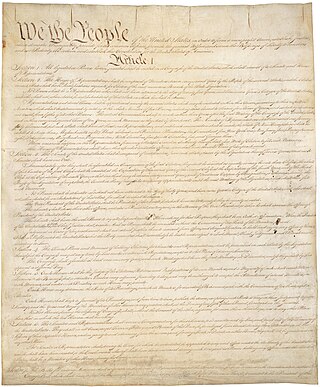

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally including seven articles, the Constitution delineates the national frame and constrains the powers of the federal government. The Constitution's first three articles embody the doctrine of the separation of powers, in which the federal government is divided into three branches: the legislative, consisting of the bicameral Congress ; the executive, consisting of the president and subordinate officers ; and the judicial, consisting of the Supreme Court and other federal courts. Article IV, Article V, and Article VI embody concepts of federalism, describing the rights and responsibilities of state governments, the states in relationship to the federal government, and the shared process of constitutional amendment. Article VII establishes the procedure subsequently used by the 13 states to ratify it. The Constitution of the United States is the oldest and longest-standing written and codified national constitution in force in the world.

The Federalist Papers is a collection of 85 articles and essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the collective pseudonym "Publius" to promote the ratification of the Constitution of the United States. The collection was commonly known as The Federalist until the name The Federalist Papers emerged in the twentieth century.

Anti-Federalism was a late-18th-century political movement that opposed the creation of a stronger U.S. federal government and which later opposed the ratification of the 1787 Constitution. The previous constitution, called the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, gave state governments more authority. Led by Patrick Henry of Virginia, Anti-Federalists worried, among other things, that the position of president, then a novelty, might evolve into a monarchy. Though the Constitution was ratified and supplanted the Articles of Confederation, Anti-Federalist influence helped lead to the passage of the Bill of Rights.

The United States Constitution has served as the supreme law of the United States since taking effect in 1789. The document was written at the 1787 Philadelphia Convention and was ratified through a series of state conventions held in 1787 and 1788. Since 1789, the Constitution has been amended twenty-seven times; particularly important amendments include the ten amendments of the United States Bill of Rights and the three Reconstruction Amendments.

Anti-Federalist Papers is the collective name given to the works written by the Founding Fathers who were opposed to, or concerned with, the merits of the United States Constitution of 1787. Starting on 25 September 1787 and running through the early 1790s, these Anti-Federalists published a series of essays arguing against the ratification of the new Constitution. They argued against the implementation of a stronger federal government without protections on certain rights. The Anti-Federalist papers failed to halt the ratification of the Constitution but they succeeded in influencing the first assembly of the United States Congress to draft the Bill of Rights. These works were authored primarily by anonymous contributors using pseudonyms such as "Brutus" and the "Federal Farmer." Unlike the Federalists, the Anti-Federalists created their works as part of an unorganized group.

Federalist No. 10 is an essay written by James Madison as the tenth of The Federalist Papers, a series of essays initiated by Alexander Hamilton arguing for the ratification of the United States Constitution. It was first published in The Daily Advertiser on November 22, 1787, under the name "Publius". Federalist No. 10 is among the most highly regarded of all American political writings.

Federalist No. 9 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the ninth of The Federalist Papers. It was first published in The Independent Journal on November 21, 1787 under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. Federalist No. 9 is titled "The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection".

Federalist No. 2, titled "Concerning Dangers From Foreign Force and Influence", is a political essay written by John Jay. It was the second of The Federalist Papers, a series of 85 essays arguing for the ratification of the United States Constitution. The essay was first published in The Independent Journal on October 31, 1787, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist Papers were published. Federalist No. 2 established the premise of nationhood that would persist through the series, addressing the issue of political union.

Federalist No. 6, titled "Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States", is a political essay written by Alexander Hamilton and the sixth of The Federalist Papers. It was first published in the Independent Journal on November 14, 1787, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist Papers were published. It is one of two essays by Hamilton advocating political union to prevent the states from going to war with one another. This argument is continued in Federalist No. 7.

Federalist No. 7, titled "The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States", is a political essay by Alexander Hamilton and the seventh of The Federalist Papers. It was first published in the Independent Journal on November 17, 1787, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist Papers were published. It is one of two essays by Hamilton advocating political union to prevent the states from going to war with one another. Federalist No. 7 continues the argument that was developed in Federalist No. 6.

Federalist Paper No. 29 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the twenty-ninth of The Federalist Papers. It was first published in The Independent Journal on January 9, 1788 under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. It is titled "Concerning the Militia". Unlike the rest of the Federalist Papers, which were published more or less in order, No. 29 did not appear until after Federalist No. 36.

Federalist Paper No. 54 is an essay by James Madison, the fifty-fourth of The Federalist Papers. It was first published by The New York Packet on February 12, 1788 under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published.

Federalist No. 66 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the sixty-sixth of The Federalist Papers. It was published on March 8, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. The title is "Objections to the Power of the Senate To Set as a Court for Impeachments Further Considered".

Federalist No. 68 is the 68th essay of The Federalist Papers, and was published on March 12, 1788. It was probably written by Alexander Hamilton under the pseudonym "Publius", the name under which all of the Federalist Papers were published. Since all of them were written under this pseudonym, who wrote what cannot be verified with certainty. Titled "The Mode of Electing the President", No. 68 describes a perspective on the process selecting the chief executive of the United States. In this essay, the author sought to convince the people of New York of the merits of the proposed constitution. Number 68 is the second in a series of 11 essays discussing the powers and limitations of the executive branch and the only one to describe the method of selecting the president.

The Federal Farmer was the pseudonym used by an Anti-Federalist who wrote a methodical assessment of the proposed United States Constitution that was among the more important documents of the ratification debate. The assessment appeared in the form of two pamphlets, the first published in November 1787 and the second in December 1787.

The First Party System was the political party system in the United States between roughly 1792 and 1824. It featured two national parties competing for control of the presidency, Congress, and the states: the Federalist Party, created largely by Alexander Hamilton, and the rival Jeffersonian Democratic-Republican Party, formed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, usually called at the time the Republican Party.

The Virginia Ratifying Convention was a convention of 168 delegates from Virginia who met in 1788 to ratify or reject the United States Constitution, which had been drafted at the Philadelphia Convention the previous year.

The drafting of the Constitution of the United States began on May 25, 1787, when the Constitutional Convention met for the first time with a quorum at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to revise the Articles of Confederation. It ended on September 17, 1787, the day the Frame of Government drafted by the convention's delegates to replace the Articles was adopted and signed. The ratification process for the Constitution began that day, and ended when the final state, Rhode Island, ratified it on May 29, 1790.

James Madison was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the 4th president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. He is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for his pivotal role in drafting and promoting the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights. Disillusioned by the weak national government established by the Articles of Confederation, he helped organize the Constitutional Convention, which produced a new constitution. Madison's Virginia Plan served as the basis for the Constitutional Convention's deliberations, and he was one of the most influential individuals at the convention. He became one of the leaders in the movement to ratify the Constitution, and he joined with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay in writing The Federalist Papers, a series of pro-ratification essays that was one of the most influential works of political science in American history.