Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case that established the principle of judicial review in the United States, meaning that American courts have the power to strike down laws and statutes they find to violate the Constitution of the United States. Decided in 1803, Marbury is regarded as the single most important decision in American constitutional law. The Court's landmark decision established that the U.S. Constitution is actual law, not just a statement of political principles and ideals. It helped define the boundary between the constitutionally separate executive and judicial branches of the federal government.

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congress. Article Three empowers the courts to handle cases or controversies arising under federal law, as well as other enumerated areas. Article Three also defines treason.

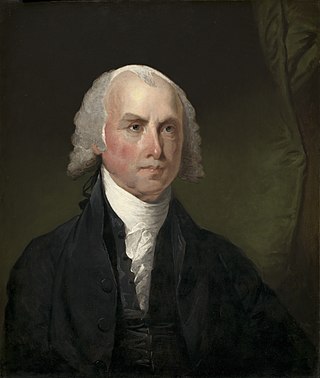

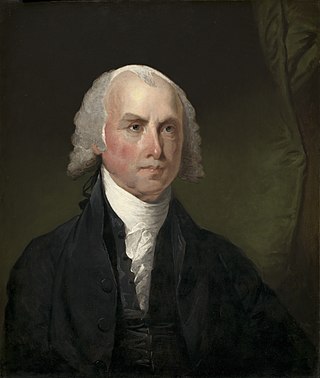

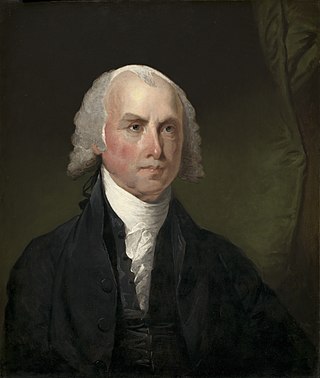

The Federalist Papers is a collection of 85 articles and essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the collective pseudonym "Publius" to promote the ratification of the Constitution of the United States. The collection was commonly known as The Federalist until the name The Federalist Papers emerged in the twentieth century.

In the United States, a state court has jurisdiction over disputes with some connection to a U.S. state. State courts handle the vast majority of civil and criminal cases in the United States; the United States federal courts are far smaller in terms of both personnel and caseload, and handle different types of cases. States often provide their trial courts with general jurisdiction and state trial courts regularly have concurrent jurisdiction with federal courts. Federal courts are courts of limited jurisdiction and their subject-matter jurisdiction arises only under federal law.

Federal common law is a term of United States law used to describe common law that is developed by the federal courts, instead of by the courts of the various states. Ever since Louis Brandeis, writing for the Supreme Court of the United States in Erie Railroad v. Tompkins (1938), overturned Joseph Story's decision in Swift v. Tyson, federal courts exercising diversity jurisdiction have applied state law as the substantive laws, with few exceptions. Nevertheless, there are several areas where federal common law continues to govern.

Hans v. Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1 (1890), was a decision of the United States Supreme Court determining that the Eleventh Amendment prohibits a citizen of a U.S. state to sue that state in a federal court. Citizens cannot bring suits against their own state for cases related to the federal constitution and federal laws. The court left open the question of whether a citizen may sue his or her state in state courts. That ambiguity was resolved in Alden v. Maine (1999), in which the Court held that a state's sovereign immunity forecloses suits against a state government in state court.

Federalist No. 78 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the seventy-eighth of The Federalist Papers. Like all of The Federalist papers, it was published under the pseudonym Publius.

Federalist No. 3, titled "The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence", is a political essay by John Jay, the third of The Federalist Papers. It was first published in The Independent Journal on November 3, 1787, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. It is the second of four essays by Jay on the benefits of political union in protecting Americans against foreign adversaries, preceded by Federalist No. 2 and followed by Federalist No. 4 and Federalist No. 5.

Federalist No. 11 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the eleventh of The Federalist Papers. It was first published in The Independent Journal on November 23, 1787 under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. It is titled "The Utility of the Union in Respect to Commercial Relations and a Navy".

Federalist No. 14 is an essay by James Madison titled "Objections to the Proposed Constitution From Extent of Territory Answered". This essay is the fourteenth of The Federalist Papers. It was first published in The New York Packet on November 30, 1787 under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. It addresses a major objection of the Anti-Federalists to the proposed United States Constitution: that the sheer size of the United States would make it impossible to govern justly as a single country. Madison touched on this issue in Federalist No. 10 and returns to it in this essay.

Federalist No. 13 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the thirteenth of The Federalist Papers. It was first published in The Independent Journal on November 28, 1787, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. It is titled "Advantage of the Union in Respect to Economy in Government".

Federalist No. 16, titled "The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union", is an essay by Alexander Hamilton. It is one of the eighty-five articles collected in the document The Federalist Papers. The entire collection of papers was written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay. Federalist Paper No. 16 was first published on December 4, 1787 by The New York Packet under the pseudonym Publius. According to James Madison, "the immediate object of them was to vindicate and recommend the new Constitution to the State of [New York] whose ratification of the instrument, was doubtful, as well as important". In addition, the articles were written and addressed "To the People of New York".

Federalist No. 25 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the twenty-fifth of The Federalist Papers. It was first published in The New York Packet on December 21, 1787, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. It continues the discussion begun in Federalist No. 24. No. 25 is titled "The Same Subject Continued: The Powers Necessary to the Common Defense Further Considered".

Federalist No. 26, titled "The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered", is an essay written by Alexander Hamilton as the twenty-sixth of The Federalist Papers. It was published on December 22, 1787, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. Federalist No. 26 expands upon the arguments of a federal military Hamilton made in No. 24 and No. 25, and it is directly continued in No. 27 and No. 28.

Federalist No. 27, titled "The Same Subject Continued: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered", is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the twenty-seventh of The Federalist Papers. It was published on December 25, 1787, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. Federalist No. 27 is the second of three successive essays covering the relationship between legislative authority and military force, preceded by Federalist No. 26, and succeeded by Federalist No. 28.

Federalist No. 49 is an essay by James Madison, the forty-ninth of The Federalist Papers. It was first published by The New York Packet on February 2, 1788, under the pseudonym "Publius", the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. It is titled "Method of Guarding Against the Encroachments of Any One Department of Government by Appealing to the People Through a Convention".

Federalist No. 76, written by Alexander Hamilton, was published on April 1, 1788. The Federalist Papers are a series of eighty-five essays written to urge the ratification of the United States Constitution. These letters were written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the name of Publius in the late 1780s. This paper discusses the arrangement of the power of appointment and the system of checks and balances. The title is "The Appointing Power of the Executive", and is the tenth in a series of 11 essays discussing the powers and limitations of the Executive branch. There are three options for entrusting power: a single individual, a select congregation, or an individual with the unanimity of the assembly. Hamilton supported bestowing the president with the nominating power but the ratifying power would be granted to the senate in order to have a process with the least bias.

Federalist No. 81 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the eighty-first of The Federalist Papers. It was published on June 25 and 28, 1788 under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. The title is "The Judiciary Continued, and the Distribution of the Judicial Authority", and it is the fourth in a series of six essays discussing the powers and limitations of the Judicial branch.

Federalist No. 82 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the eighty-second of The Federalist Papers. It was published on July 2, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. Its title is "The Judiciary Continued", and it is the fifth in a series of six essays discussing the powers and limitations of the judicial branch of government.

In the United States, judicial review is the legal power of a court to determine if a statute, treaty, or administrative regulation contradicts or violates the provisions of existing law, a State Constitution, or ultimately the United States Constitution. While the U.S. Constitution does not explicitly define the power of judicial review, the authority for judicial review in the United States has been inferred from the structure, provisions, and history of the Constitution.