The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the national frame and constraints of government. The Constitution's first three articles embody the doctrine of the separation of powers, whereby the federal government is divided into three branches: the legislative, consisting of the bicameral Congress ; the executive, consisting of the president and subordinate officers ; and the judicial, consisting of the Supreme Court and other federal courts. Article IV, Article V, and Article VI embody concepts of federalism, describing the rights and responsibilities of state governments, the states in relationship to the federal government, and the shared process of constitutional amendment. Article VII establishes the procedure subsequently used by the 13 states to ratify it. The Constitution of the United States is the oldest and longest-standing written and codified national constitution in force in the world today.

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congress. Article Three empowers the courts to handle cases or controversies arising under federal law, as well as other enumerated areas. Article Three also defines treason.

The Federalist Papers is a collection of 85 articles and essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the collective pseudonym "Publius" to promote the ratification of the Constitution of the United States. The collection was commonly known as The Federalist until the name The Federalist Papers emerged in the 20th century.

Chisholm v. Georgia, 2 U.S. 419 (1793), is considered the first United States Supreme Court case of significance and impact. Since the case was argued prior to the formal pronouncement of judicial review by Marbury v. Madison (1803), there was little available legal precedent. The Court in a 4–1 decision ruled in favor of Alexander Chisholm, executor of an estate of a citizen of South Carolina, holding that Article III, Section 2 grants federal courts jurisdiction in cases between a state and a citizen of another state wherein the state is the defendant.

The Necessary and Proper Clause, also known as the Elastic Clause, is a clause in Article I, Section 8 of the United States Constitution:

The Congress shall have Power... To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

The Preamble to the United States Constitution, beginning with the words We the People, is a brief introductory statement of the US Constitution's fundamental purposes and guiding principles. Courts have referred to it as reliable evidence of the Founding Fathers' intentions regarding the Constitution's meaning and what they hoped the Constitution would achieve.

Hans v. Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1 (1890), was a decision of the United States Supreme Court determining that the Eleventh Amendment prohibits a citizen of a U.S. state to sue that state in a federal court. Citizens cannot bring suits against their own state for cases related to the federal constitution and federal laws. The court left open the question of whether a citizen may sue his or her state in state courts. That ambiguity was resolved in Alden v. Maine (1999), in which the Court held that a state's sovereign immunity forecloses suits against a state government in state court.

Federalist No. 10 is an essay written by James Madison as the tenth of The Federalist Papers, a series of essays initiated by Alexander Hamilton arguing for the ratification of the United States Constitution. It was first published in The Daily Advertiser on November 22, 1787, under the name "Publius". Federalist No. 10 is among the most highly regarded of all American political writings.

Federalist No. 78 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the seventy-eighth of The Federalist Papers. Like all of The Federalist papers, it was published under the pseudonym Publius.

Federalist No. 39, titled "The conformity of the Plan to Republican Principles", is an essay by James Madison, the thirty-ninth of The Federalist Papers, first published by The Independent Journal on January 16, 1788. Madison defines a republican form of government, and he also considers whether the nation is federal or national: a confederacy, or consolidation of states.

Federalist No. 14 is an essay by James Madison titled "Objections to the Proposed Constitution From Extent of Territory Answered". This essay is the fourteenth of The Federalist Papers. It was first published in The New York Packet on November 30, 1787 under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. It addresses a major objection of the Anti-Federalists to the proposed United States Constitution: that the sheer size of the United States would make it impossible to govern justly as a single country. Madison touched on this issue in Federalist No. 10 and returns to it in this essay.

Federalist No. 27, titled "The Same Subject Continued: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered", is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the twenty-seventh of The Federalist Papers. It was published on December 25, 1787, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. Federalist No. 27 is the second of three successive essays covering the relationship between legislative authority and military force, preceded by Federalist No. 26, and succeeded by Federalist No. 28.

Federalist No. 66 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the sixty-sixth of The Federalist Papers. It was published on March 8, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. The title is "Objections to the Power of the Senate To Set as a Court for Impeachments Further Considered".

Federalist No. 69 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the sixty-ninth of The Federalist Papers. It was published on March 14, 1788 under the pseudonym Publius, under which all The Federalist papers were published. The title is "The Real Character of the Executive", and is the third in a series of 11 essays discussing the powers and limitations of the Executive branch in response to the Anti-Federalist Papers, and in comparison to the King of England's powers.

Federalist No. 80 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the eightieth of The Federalist Papers. It was published on June 21, 1788 under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. It is titled "The Powers of the Judiciary", and it is the third in a series of six essays discussing the powers and limitations of the judicial branch.

Federalist No. 82 is an essay by Alexander Hamilton, the eighty-second of The Federalist Papers. It was published on July 2, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published. Its title is "The Judiciary Continued", and it is the fifth in a series of six essays discussing the powers and limitations of the judicial branch of government.

In the United States, judicial review is the legal power of a court to determine if a statute, treaty, or administrative regulation contradicts or violates the provisions of existing law, a State Constitution, or ultimately the United States Constitution. While the U.S. Constitution does not explicitly define the power of judicial review, the authority for judicial review in the United States has been inferred from the structure, provisions, and history of the Constitution.

Nullification, in United States constitutional history, is a legal theory that a state has the right to nullify, or invalidate, any federal laws which they deem unconstitutional with respect to the United States Constitution. There are similar theories that any officer, jury, or individual may do the same. The theory of state nullification has never been legally upheld by federal courts, although jury nullification has.

In United States law, the federal government as well as state and tribal governments generally enjoy sovereign immunity, also known as governmental immunity, from lawsuits. Local governments in most jurisdictions enjoy immunity from some forms of suit, particularly in tort. The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act provides foreign governments, including state-owned companies, with a related form of immunity—state immunity—that shields them from lawsuits except in relation to certain actions relating to commercial activity in the United States. The principle of sovereign immunity in US law was inherited from the English common law legal maxim rex non potest peccare, meaning "the king can do no wrong." In some situations, sovereign immunity may be waived by law.

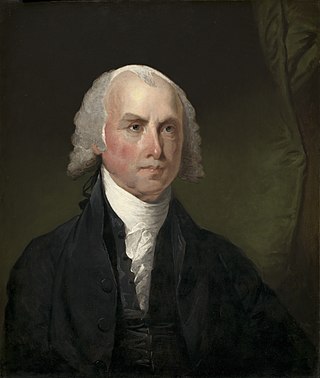

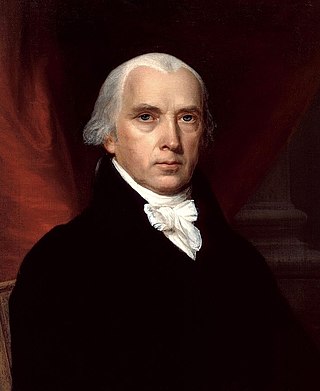

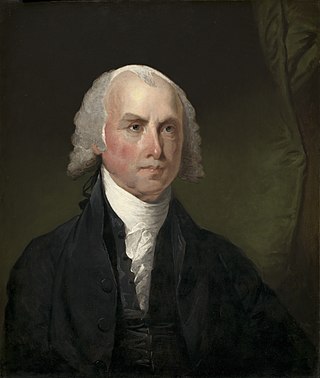

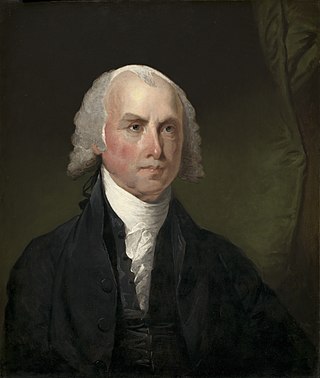

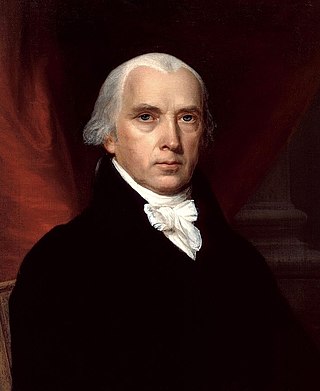

James Madison was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the 4th president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. He is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for his pivotal role in drafting and promoting the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights. Disillusioned by the weak national government established by the Articles of Confederation, he helped organize the Constitutional Convention, which produced a new constitution. Madison's Virginia Plan served as the basis for the Constitutional Convention's deliberations, and he was one of the most influential individuals at the convention. He became one of the leaders in the movement to ratify the Constitution, and he joined with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay in writing The Federalist Papers, a series of pro-ratification essays that was one of the most influential works of political science in American history.