Dianetics is a set of ideas and practices invented in 1950 by science fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard regarding the human mind. Dianetics was originally conceived as a form of psychological treatment, but was rejected by the psychological and medical establishments as pseudoscientific. Dianetics was the precursor to Scientology and has since been incorporated into it.

Edward Elmer Smith was an American food engineer and science-fiction author, best known for the Lensman and Skylark series. He is sometimes called the father of space opera.

John Wood Campbell Jr. was an American science fiction writer and editor. He was editor of Astounding Science Fiction from late 1937 until his death and was part of the Golden Age of Science Fiction. Campbell wrote super-science space opera under his own name and stories under his primary pseudonym, Don A. Stuart. Campbell also used the pen names Karl Van Kampen and Arthur McCann. His novella Who Goes There? was adapted as the films The Thing from Another World (1951), The Thing (1982), and The Thing (2011).

Lafayette Ronald Hubbard was an American author and the founder of Scientology. A prolific writer of pulp science fiction and fantasy novels in his early career, in 1950 he authored Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health and established organizations to promote and practice Dianetics techniques. Hubbard created Scientology in 1952 after losing the intellectual rights to his literature on Dianetics in bankruptcy. He would lead the Church of Scientology, variously described as a cult, a new religious movement, or a business, until his death in 1986.

Xenu, also called Xemu, is a figure in the Church of Scientology's secret "Advanced Technology", a sacred and esoteric teaching. According to the "Technology", Xenu was the extraterrestrial ruler of a "Galactic Confederacy" who brought billions of his people to Earth in DC-8-like spacecraft 75 million years ago, stacked them around volcanoes, and killed them with hydrogen bombs. Official Scientology scriptures hold that the thetans of these aliens adhere to humans, causing spiritual harm.

In American science fiction of the 1950s and '60s, psionics was a proposed discipline that applied principles of engineering to the study of paranormal or psychic phenomena, such as extrasensory perception, telepathy and psychokinesis. The term is a blend word of psi and the -onics from electronics. The word "psionics" began as, and always remained, a term of art within the science fiction community and—despite the promotional efforts of editor John W. Campbell, Jr.—it never achieved general currency, even among academic parapsychologists. In the years after the term was coined in 1951, it became increasingly evident that no scientific evidence supports the existence of "psionic" abilities.

Unknown was an American pulp fantasy fiction magazine, published from 1939 to 1943 by Street & Smith, and edited by John W. Campbell. Unknown was a companion to Street & Smith's science fiction pulp, Astounding Science Fiction, which was also edited by Campbell at the time; many authors and illustrators contributed to both magazines. The leading fantasy magazine in the 1930s was Weird Tales, which focused on shock and horror. Campbell wanted to publish a fantasy magazine with more finesse and humor than Weird Tales, and put his plans into action when Eric Frank Russell sent him the manuscript of his novel Sinister Barrier, about aliens who own the human race. Unknown's first issue appeared in March 1939; in addition to Sinister Barrier, it included H. L. Gold's "Trouble With Water", a humorous fantasy about a New Yorker who meets a water gnome. Gold's story was the first of many in Unknown to combine commonplace reality with the fantastic.

Revolt in the Stars is a science fiction film screenplay written by Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard in 1977. It tells the space opera story of how an evil galactic dictator, named Xenu, massacres many of his subjects by transporting them to Earth and killing them with atomic bombs. L. Ron Hubbard had already presented this story to his followers, as a true account of events that happened 75 million years ago, in a secret level of Scientology scripture called Operating Thetan, Level III. The screenplay was promoted around Hollywood circles in 1979, but attempts at fundraising and obtaining financing fell through, and the film was never made. Unofficial copies circulate on the internet.

Dianetics: The Evolution of a Science is a book written by L. Ron Hubbard. Originally published in May 1950 as an article in Astounding Science Fiction, and immediately preceding the publication of his book Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health, it was expanded and republished as a 48-page book in 1955 by Hubbard Association of Scientologists International Ltd. In 2007, it was republished by Bridge Publications as a 213-page book — part of the re-release of the "basic books" of Scientology. The book is considered part of Scientology's canon.

Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health, sometimes abbreviated as DMSMH, is a book by L. Ron Hubbard about Dianetics, a pseudoscientific system that he claimed to have developed from a combination of personal experience, basic principles of Eastern philosophy and the work of Sigmund Freud. The book is considered part of Scientology's canon. It is colloquially referred to by Scientologists as Book One. The book launched the movement, which later defined itself as a religion, in 1950. As of 2013, New Era Publications, the international publishing company of Hubbard's works, sells the book in English and in 50 other languages.

History of Dianetics and Scientology begins around 1950. During the late 1940s, L. Ron Hubbard began developing a mental therapy system which he called Dianetics. Hubbard had tried to interest the medical profession in his techniques, including the Gerontological Society, the Journal of the American Medical Association, and the American Journal of Psychiatry, but his work was rejected for not containing sufficient evidence of efficacy to be acceptable.

Battlefield Earth is a 2000 American science fiction film based on the 1982 novel of the same name by Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard. It was directed by Roger Christian and stars John Travolta, Barry Pepper, and Forest Whitaker. The film follows a rebellion against the alien Psychlos, who have ruled Earth for 1,000 years.

Battlefield Earth: A Saga of the Year 3000 is a 1982 science fiction novel written by L. Ron Hubbard, founder of Scientology. He also composed a soundtrack to the book called Space Jazz.

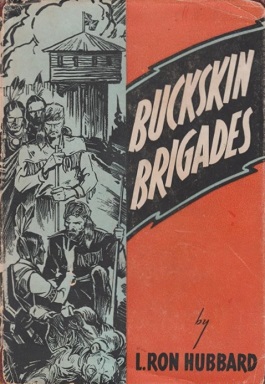

Buckskin Brigades is a Western novel written by L. Ron Hubbard, first published July 30, 1937. The work was Hubbard's first hard-covered book, and his first published novel. The next year he became a contributor to Astounding Science Fiction. Winfred Blevins wrote the introduction to the book. Some sources state that as a young man, Hubbard became a blood brother to the Piegan Blackfeet Native American tribe while living in Montana, though this claim is disputed. Hubbard incorporates historical background from the Blackfeet tribe into the book.

Space Jazz: The soundtrack of the book Battlefield Earth is a music album and soundtrack companion to the novel Battlefield Earth by L. Ron Hubbard, released in 1982. Hubbard composed the music for the album.

To the Stars is a science fiction novel by American writer L. Ron Hubbard. The novel's story is set in a dystopian future, and chronicles the experiences of protagonist Alan Corday aboard a starship called the Hound of Heaven as he copes with the travails of time dilation from traveling at near light speed. Corday is kidnapped by the ship's captain and forced to become a member of their crew, and when he next returns to Earth his fiancée has aged and barely remembers him. He becomes accustomed to life aboard the ship, and when the captain dies Corday assumes command.

Lafayette Ronald Hubbard, better known as L. Ron Hubbard, was an American pulp fiction author. He wrote in a wide variety of genres, including science fiction, fantasy, adventure fiction, aviation, travel, mystery, western, and romance. His United States publisher and distributor is Galaxy Press. He is perhaps best known for his self-help book, the #1 New York Times bestseller Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health, and as the founder of the Church of Scientology.

Typewriter in the Sky is a science fantasy novel by American writer L. Ron Hubbard. The protagonist Mike de Wolf finds himself inside the story of his friend Horace Hackett's book. He must survive conflict on the high seas in the Caribbean during the 17th century, before eventually returning to his native New York City. Each time a significant event occurs to the protagonist in the story he hears the sounds of a typewriter in the sky. At the story's conclusion, de Wolf wonders if he is still a character in someone else's story. The work was first published in a two-part serial format in 1940 in Unknown Fantasy Fiction. It was twice published as a combined book with Hubbard's work Fear. In 1995 Bridge Publications re-released the work along with an audio edition.

A. Merritt's Fantasy Magazine was an American pulp magazine which published five issues from December 1949 to October 1950. It took its name from fantasy writer A. Merritt, who had died in 1943, and it aimed to capitalize on Merritt's popularity. It was published by Popular Publications, alternating months with Fantastic Novels, another title of theirs. It may have been edited by Mary Gnaedinger, who also edited Fantastic Novels and Famous Fantastic Mysteries. It was a companion to Famous Fantastic Mysteries, and like that magazine mostly reprinted science-fiction and fantasy classics from earlier decades.

Science-fiction and fantasy magazines began to be published in the United States in the 1920s. Stories with science-fiction themes had been appearing for decades in pulp magazines such as Argosy, but there were no magazines that specialized in a single genre until 1915, when Street & Smith, one of the major pulp publishers, brought out Detective Story Magazine. The first magazine to focus solely on fantasy and horror was Weird Tales, which was launched in 1923, and established itself as the leading weird fiction magazine over the next two decades; writers such as H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith and Robert E. Howard became regular contributors. In 1926 Weird Tales was joined by Amazing Stories, published by Hugo Gernsback; Amazing printed only science fiction, and no fantasy. Gernsback included a letter column in Amazing Stories, and this led to the creation of organized science-fiction fandom, as fans contacted each other using the addresses published with the letters. Gernsback wanted the fiction he printed to be scientifically accurate, and educational, as well as entertaining, but found it difficult to obtain stories that met his goals; he printed "The Moon Pool" by Abraham Merritt in 1927, despite it being completely unscientific. Gernsback lost control of Amazing Stories in 1929, but quickly started several new magazines. Wonder Stories, one of Gernsback's titles, was edited by David Lasser, who worked to improve the quality of the fiction he received. Another early competitor was Astounding Stories of Super-Science, which appeared in 1930, edited by Harry Bates, but Bates printed only the most basic adventure stories with minimal scientific content, and little of the material from his era is now remembered.