A surface-to-air missile (SAM), also known as a ground-to-air missile (GTAM) or surface-to-air guided weapon (SAGW), is a missile designed to be launched from the ground or the sea to destroy aircraft or other missiles. It is one type of anti-aircraft system; in modern armed forces, missiles have replaced most other forms of dedicated anti-aircraft weapons, with anti-aircraft guns pushed into specialized roles.

An air-to-air missile (AAM) is a missile fired from an aircraft for the purpose of destroying another aircraft. AAMs are typically powered by one or more rocket motors, usually solid fueled but sometimes liquid fueled. Ramjet engines, as used on the Meteor, are emerging as propulsion that will enable future medium- to long-range missiles to maintain higher average speed across their engagement envelope.

The Fairey Aviation Company Limited was a British aircraft manufacturer of the first half of the 20th century based in Hayes in Middlesex and Heaton Chapel and RAF Ringway in Cheshire that designed important military aircraft, including the Fairey III family, the Swordfish, Firefly, and Gannet. It had a strong presence in the supply of naval aircraft, and also built bombers for the RAF.

The Bristol Bloodhound is a British ramjet powered surface-to-air missile developed during the 1950s. It served as the UK's main air defence weapon into the 1990s and was in large-scale service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the forces of four other countries.

Fairey's Green Cheese, a rainbow code name, was a British-made radar-guided anti-ship missile project of the 1950s. It was a development of the earlier and much larger Blue Boar television guided glide bomb, making it smaller, replacing the television camera with the radar seeker from the Red Dean air-to-air missile, and carrying a smaller warhead of 1,700 pounds (770 kg).

Seaslug was a first-generation surface-to-air missile designed by Armstrong Whitworth for use by the Royal Navy. Tracing its history as far back as 1943's LOPGAP design, it came into operational service in 1961 and was still in use at the time of the Falklands War in 1982.

Blue Water was a British battlefield nuclear missile of the early 1960s, intended to replace the MGM-5 Corporal, which was becoming obsolete. With roughly the same role and range as Corporal, the solid-fuel Blue Water was far simpler to use and would be significantly easier to support in the field. It was seen as a replacement for Corporal both in the UK as well as other NATO operators, notably Germany and possibly Turkey.

The de Havilland Firestreak is a British first-generation, passive infrared homing air-to-air missile. It was developed by de Havilland Propellers in the early 1950s, entering service in 1957. It was the first such weapon to enter active service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) and Fleet Air Arm, equipping the English Electric Lightning, de Havilland Sea Vixen and Gloster Javelin. It was a rear-aspect, fire and forget pursuit weapon, with a field of attack of 20 degrees either side of the target.

The Hawker Siddeley Red Top was the third indigenous British air-to-air missile to enter service, following the de Havilland Firestreak and limited-service Fireflash. It was used to replace the Firestreak on the de Havilland Sea Vixen and later models of the English Electric Lightning.

The English Electric Thunderbird was a British surface-to-air missile produced for the British Army. Thunderbird was primarily intended to attack higher altitude targets at ranges up to approximately 30 miles (48 km), providing wide-area air defence for the Army in the field. Anti-aircraft guns were still used for lower altitude threats. Thunderbird entered service in 1959 and underwent a major mid-life upgrade to Thunderbird 2 in 1966, before being slowly phased out by 1977. Ex-Army Thunderbirds were also operated by the Royal Saudi Air Force after 1967.

The Rainbow Codes were a series of code names used to disguise the nature of various British military research projects. They were mainly used by the Ministry of Supply from the end of the Second World War until 1958, when the ministry was broken up and its functions distributed among the forces. The codes were replaced by an alphanumeric code system.

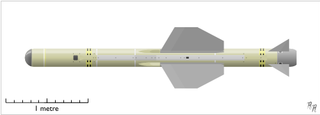

Red Dean, a rainbow code name, was a large air-to-air missile developed for the Royal Air Force during the 1950s. Originally planned to use an active radar seeker to offer all-aspect performance and true fire-and-forget engagements, the valve-based electronics demanded a missile of prodigious size.

Operational Requirement F.155 was a specification issued by the British Ministry of Supply on 15 January 1955 for an interceptor aircraft to defend the United Kingdom from Soviet high-flying nuclear-armed supersonic bombers.

The Hawker P.1103 was a design by Hawker Aircraft to meet the British Operational Requirement F.155; it did not progress further than the drawing board.

The Short Range Air-to-Air Missile, or SRAAM for short, initially known as Taildog, was an experimental British infrared homing air-to-air missile, developed between 1968 and 1980 by Hawker Siddeley Dynamics. It was designed to be very manoeuvrable for use at short range in a dogfight situation. The SRAAM was unusual in that it was launched from a launch tube instead of being attached to a launch rail, allowing two to be carried on a single mounting point.

The Fairey Aviation Stooge was a command guided surface-to-air missile (SAM) development project carried out in the United Kingdom starting in World War II. Development dates to a British Army request from 1944, but the work was taken over by the Royal Navy as a potential counter to the Kamikaze threat. Development was not complete when the war ended, but the Ministry of Supply funded further development and numerous test launches into 1947, assisting in the development of more advanced successor missiles.

Blue Envoy was a British project to develop a ramjet-powered surface-to-air missile. It was tasked with countering supersonic bomber aircraft launching stand-off missiles, and thus had to have very long range and high-speed capabilities. The final design was expected to fly at Mach 3 with a maximum range of over 200 miles (320 km).

Spaniel was a series of experimental British missiles of the Second World War. They began as surface-to-air missile designs developed by the Air Ministry from 1941. Based on the 3-inch Unrotated Projectile anti-aircraft rocket, it proved to have too little performance to easily reach typical bomber altitudes, leading to further development as an air-to-air missile carried aloft by heavy fighters. Some progress had been made by 1942 when the program was cancelled as the threat of German air attack dwindled. Further research was directed at a dedicated air-to-air design, Artemis.

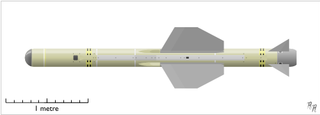

Red Hebe was a large active radar homing air-to-air missile developed by Vickers for the Royal Air Force's Operational Requirement F.155 interceptor aircraft. It was a development of the earlier Red Dean, which was not suitable for launch by the new supersonic aircraft. Before progressing much beyond advanced design studies, F.155 was cancelled in the aftermath of the 1957 Defence White Paper which moved Britain's attention from strategic bombers to ballistic missiles. With no other suitable platform, Red Hebe was cancelled as well.