Semantics is the linguistic and philosophical study of meaning in language, programming languages, formal logics, and semiotics. It is concerned with the relationship between signifiers—like words, phrases, signs, and symbols—and what they stand for in reality, their denotation.

Cognitive linguistics (CL) is an interdisciplinary branch of linguistics, combining knowledge and research from both psychology and linguistics. It describes how language interacts with cognition, how language forms our thoughts, and the evolution of language parallel with the change in the common mindset across time.

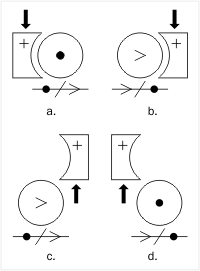

An image schema is a recurring structure within our cognitive processes which establishes patterns of understanding and reasoning. Image schemas are formed from our bodily interactions, from linguistic experience, and from historical context. The term is explained in Mark Johnson's book The Body in the Mind; in case study 2 of George Lakoff's Women, Fire and Dangerous Things; by Rudolf Arnheim in Visual Thinking; and more recently, by Tim Rohrer's 2006 book chapter Image Schemata in the Brain.

In linguistics, a causative is a valency-increasing operation that indicates that a subject either causes someone or something else to do or be something or causes a change in state of a non-volitional event. Normally, it brings in a new argument, A, into a transitive clause, with the original subject S becoming the object O.

Ray Jackendoff is an American linguist. He is professor of philosophy, Seth Merrin Chair in the Humanities and, with Daniel Dennett, co-director of the Center for Cognitive Studies at Tufts University. He has always straddled the boundary between generative linguistics and cognitive linguistics, committed to both the existence of an innate universal grammar and to giving an account of language that is consistent with the current understanding of the human mind and cognition.

A linguistic universal is a pattern that occurs systematically across natural languages, potentially true for all of them. For example, All languages have nouns and verbs, or If a language is spoken, it has consonants and vowels. Research in this area of linguistics is closely tied to the study of linguistic typology, and intends to reveal generalizations across languages, likely tied to cognition, perception, or other abilities of the mind. The field originates from discussions influenced by Noam Chomsky's proposal of a Universal Grammar, but was largely pioneered by the linguist Joseph Greenberg, who derived a set of forty-five basic universals, mostly dealing with syntax, from a study of some thirty languages.

In generative grammar, a theta role or θ-role is the formal device for representing syntactic argument structure—the number and type of noun phrases—required syntactically by a particular verb. For example, the verb put requires three arguments.

Conceptual semantics is a framework for semantic analysis developed mainly by Ray Jackendoff in 1976. Its aim is to provide a characterization of the conceptual elements by which a person understands words and sentences, and thus to provide an explanatory semantic representation. Explanatory in this sense refers to the ability of a given linguistic theory to describe how a component of language is acquired by a child.

Leonard Talmy is an emeritus professor of linguistics and philosophy at the University at Buffalo in New York. He is known for his pioneering work in cognitive linguistics, more specifically, in the relationship between semantic and formal linguistic structures and the connections between semantic typologies and universals. He is also specialized in the study of Yiddish and Native American linguistics.

The mentalist postulate is the thesis that meaning in natural language is an information structure that is mentally encoded by human beings. It is a basic premise of some branches of cognitive semantics. Semantic theories implicitly or explicitly incorporating the mentalist postulate include force dynamics and conceptual semantics.

Focus is a grammatical category that determines which part of the sentence contributes new, non-derivable, or contrastive information. Focus is related to information structure. Contrastive focus specifically refers to the coding of information that is contrary to the presuppositions of the interlocutor.

Intensional logic is an approach to predicate logic that extends first-order logic, which has quantifiers that range over the individuals of a universe (extensions), by additional quantifiers that range over terms that may have such individuals as their value (intensions). The distinction between intensional and extensional entities is parallel to the distinction between sense and reference.

Cognitive semantics is part of the cognitive linguistics movement. Semantics is the study of linguistic meaning. Cognitive semantics holds that language is part of a more general human cognitive ability, and can therefore only describe the world as people conceive of it. It is implicit that different linguistic communities conceive of simple things and processes in the world differently, not necessarily some difference between a person's conceptual world and the real world.

Linguistic competence is the system of linguistic knowledge possessed by native speakers of a language. It is distinguished from linguistic performance, which is the way a language system is used in communication. Noam Chomsky introduced this concept in his elaboration of generative grammar, where it has been widely adopted and competence is the only level of language that is studied.

In linguistics, volition is a concept that distinguishes whether the subject, or agent of a particular sentence intended an action or not. Simply, it is the intentional or unintentional nature of an action. Volition concerns the idea of control and for the purposes outside of psychology and cognitive science, is considered the same as intention in linguistics. Volition can then be expressed in a given language using a variety of possible methods. These sentence forms usually indicate that a given action has been done intentionally, or willingly. There are various ways of marking volition cross-linguistically. When using verbs of volition in English, like want or prefer, these verbs are not expressly marked. Other languages handle this with affixes, while others have complex structural consequences of volitional or non-volitional encoding.

Fictive motion is the metaphorical motion of an object or abstraction through space. Fictive motion has become a subject of study in psycholinguistics and cognitive linguistics. In fictive motion sentences, a motion verb applies to a subject that is not literally capable of movement in the physical world, as in the sentence, "The fence runs along the perimeter of the house." Fictive motion is so called because it is attributed to material states, objects, or abstract concepts, that cannot (sensibly) be said to move themselves through physical space. Fictive motion sentences are pervasive in English and other languages.

Lexicalization is the process of adding words, set phrases, or word patterns to a language – that is, of adding items to a language's lexicon.

In certain theories of linguistics, thematic relations, also known as semantic roles, are the various roles that a noun phrase may play with respect to the action or state described by a governing verb, commonly the sentence's main verb. For example, in the sentence "Susan ate an apple", Susan is the doer of the eating, so she is an agent; the apple is the item that is eaten, so it is a patient. While most modern linguistic theories make reference to such relations in one form or another, the general term, as well as the terms for specific relations, varies: "participant role", "semantic role", and "deep case" have also been employed with similar sense.

Cognitive sociolinguistics is an emerging field of linguistics that aims to account for linguistic variation in social settings with a cognitive explanatory framework. The goal of cognitive sociolinguists is to build a mental model of society, individuals, institutions and their relations to one another. Cognitive sociolinguists also strive to combine theories and methods used in cognitive linguistics and sociolinguistics so as to provide a more productive framework for future research on language variation. This burgeoning field concerning social implications on cognitive linguistics has yet received universal recognition.

In historical linguistics, subjectification is a language change process in which a linguistic expression acquires meanings that convey the speaker's attitude or viewpoint. An English example is the word while, which, in Middle English, had only the sense of 'at the same time that'. It later acquired the meaning of 'although', indicating a concession on the part of the speaker.