Related Research Articles

Freedom of religion in Mauritania is limited by the Government. The constitution establishes the country as an Islamic republic and decrees that Islam is the religion of its citizens and the State.

Freedom of religion in Afghanistan changed during the Islamic Republic installed in 2002 following a U.S.-led invasion that displaced the former Taliban government.

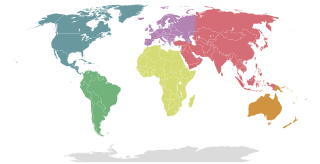

The status of religious freedom around the world varies from country to country. States can differ based on whether or not they guarantee equal treatment under law for followers of different religions, whether they establish a state religion, the extent to which religious organizations operating within the country are policed, and the extent to which religious law is used as a basis for the country's legal code.

Christianity in the Comoros is a minority religion. In 2017, Roman Catholics in the Comoros number about 4,300 persons ; Protestants number about 1,678. Figures in 2020 show that this has gone down to 0.3% Catholic and 0.15% Protestant.

The 2008 Constitution of Maldives designates Sunni Islam as the state religion. Only Sunni Muslims are allowed to hold citizenship in the country and citizens may practice Sunni Islam only. Non-Muslim citizens of other nations can practice their faith only in private and are barred from evangelizing or propagating their faith. All residents are required to teach their children the Muslim faith. The president, ministers, parliamentarians, and chiefs of the atolls are required to be Sunni Muslims. Government regulations are based on Islamic law. Only certified Muslim scholars can give fatawa.

According to U.S. government estimates, in 2022 Turkmenistan is 89% Muslim, 9% Eastern Orthodox Christian and 2% other religions. In 2023, the country was scored zero out of 4 for religious freedom; it was noted that restrictions have tightened since 2016. In the same year it was ranked the 26th worst place in the world to be a Christian.

The constitution of Brunei states that while the official religion is the Shafi’i school of Sunni Islam, all other religions may be practiced “in peace and harmony.” Apostasy and blasphemy are legally punishable by corporal and capital punishment, including stoning to death, amputation of hands or feet, or caning. Only caning has been used since 1957.

The Constitution provides for freedom of religion, and the government has generally respected this right in practice. Buddhism is the state religion.

The Constitution provides for the freedom to practice the rights of one's religion and faith in accordance with the customs that are observed in the kingdom, unless they violate public order or morality. The state religion is Islam. The Government prohibits conversion from Islam and proselytization of Muslims.

The Constitution of Kuwait provides for religious freedom. The constitution of Kuwait provides for absolute freedom of belief and for freedom of religious practice. The constitution stated that Islam is the state religion and that Sharia is a source of legislation. In general, citizens were open and tolerant of other religious groups. Regional events contributed to increased sectarian tensions between Sunnis and Shia.

The Constitution provides for freedom of religion and creeds and the exercise of all religious rites provided that the public order is not disturbed. The Constitution declares equality of rights and duties for all citizens without discrimination or preference but establishes a balance of power among the major religious groups. The Government generally respected these rights; however restricted the constitutional provision for apportioning political offices according to religious affiliation since the National Pact agreement. There were periodic reports of tension between religious groups, attributable to competition for political power, and citizens continued to struggle with the legacy of the civil war that was fought along sectarian lines. Despite sectarian tensions caused by the competition for political power, Lebanese continued to coexist.

The Basic Law, in accordance with tradition, declares that Islam is the state religion and that Shari'a is the source of legislation. It also prohibits discrimination based on religion and provides for the freedom to practice religious rites as long as doing so does not disrupt public order. The government generally respected this right, but within defined parameters that placed limitations on the right in practice. While the government continued to protect the free practice of religion in general, it formalized previously unwritten prohibitions on religious gatherings in locations other than government-approved houses of worship, and on non-Islamic institutions issuing publications within their communities, without prior approval from the Ministry of Endowments and Religious Affairs (MERA). There were no reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious belief or practice.

In Qatar, the Constitution, as well as certain laws, provide for freedom of association, public assembly, and worship in accordance with the requirements of public order and morality. Notwithstanding this, the law prohibits proselytizing by non-Muslims and places some restrictions on public worship. Islam is the state religion.

The constitution of the Syrian Arab Republic guarantees freedom of religion. Syria has had two constitutions: one passed in 1973, and one in 2012 through the 2012 Syrian constitutional referendum. Opposition groups rejected the referendum; claiming that the vote was rigged.

The Constitution of Yemen provides for freedom of religion, and the Government generally respected this right in practice; however, there were some restrictions. The Constitution declares that Islam is the state religion, and that Shari'a is the source of all legislation. Government policy continued to contribute to the generally free practice of religion; however, there were some restrictions. Muslims and followers of religious groups other than Islam are free to worship according to their beliefs, but the Government prohibits conversion from Islam and the proselytization of Muslims. Although relations among religious groups continued to contribute to religious freedom, there were some reports of societal abuses and discrimination based on religious belief or practice. There were isolated attacks on Jews and some prominent Zaydi Muslims felt targeted by government entities for their religious affiliation. Government military reengagement in the Saada governorate caused political, tribal, and religious tensions to reemerge in January 2007, following the third military clash with rebels associated with the al-Houthi family, who adhere to the Zaydi school of Shi'a Islam.

The Bulgarian constitution states that freedom of conscience and choice of religion are inviolable and prohibits religious discrimination; however, the constitution designates Eastern Orthodox Christianity as the "traditional" religion of the country.

The predominant religion in the Comoros is Islam, with a small Christian minority. Although the constitution, as revised in 2018, removed the reference to a state religion in the 2009 constitution, stating simply that Sunni Islam is the source of national identity, a 2008 law promulgated in January 2013 outlawed the practice of other forms of Islam in the country. Propagation of non-Islamic religions is prohibited.

Freedom of religion in Morocco refers to the extent to which people in Morocco are freely able to practice their religious beliefs, taking into account both government policies and societal attitudes toward religious groups. The state religion of Morocco is Islam. The government plays an active role in determining and policing religious practice for Muslims, and disrespecting Islam in public can carry punishments in the forms of fines and imprisonment.

The status of religious freedom in Africa varies from country to country. States can differ based on whether or not they guarantee equal treatment under law for followers of different religions, whether they establish a state religion, the extent to which religious organizations operating within the country are policed, and the extent to which religious law is used as a basis for the country's legal code.

The status of religious freedom in Asia varies from country to country. States can differ based on whether or not they guarantee equal treatment under law for followers of different religions, whether they establish a state religion, the extent to which religious organizations operating within the country are policed, and the extent to which religious law is used as a basis for the country's legal code.

References

- ↑ US State Dept 2022 report

- ↑ The ARDA website, retrieved 2023-08-01

- ↑ Freedom House website, retrieved 2023-08-01

- ↑ "2009 International Religious Freedom Report". US Department of State. October 26, 2009. Archived from the original on November 30, 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ↑ US State Dept 2022 report

- 1 2 "Comoros's Constitution of 2001 with Amendments through 2009" (PDF). Constitute Project. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ↑ "Comoros Flag and Description". World Atlas. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ↑ "Comoros". 2013 US State Department Report on Religious Freedom. Retrieved 25 May 2016.