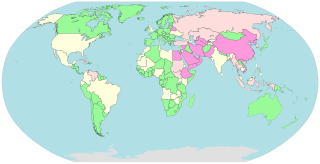

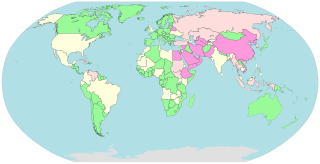

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions that are falsifiable, and can extend to concepts that are more abstract than reputation – like dignity and honour. In the English-speaking world, the law of defamation traditionally distinguishes between libel and slander. It is treated as a civil wrong, as a criminal offence, or both.

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exercised freely. Such freedom implies the absence of interference from an overreaching state; its preservation may be sought through a constitution or other legal protection and security. It is in opposition to paid press, where communities, police organizations, and governments are paid for their copyrights.

Human rights in Armenia tend to be better than those in most former Soviet republics and have drawn closer to acceptable standards, especially economically. In October 2023, Armenia ratified the Rome statute, whereby Armenia will become a full member of the International Criminal Court.

Censorship in Turkey is regulated by domestic and international legislation, the latter taking precedence over domestic law, according to Article 90 of the Constitution of Turkey.

The current government of Russia maintains laws and practices that make it difficult for directors of mass-media outlets to carry out independent policies. These laws and practices also hinder the ability of journalists to access sources of information and to work without outside pressure. Media inside Russia includes television and radio channels, periodicals, and Internet media, which according to the laws of the Russian Federation may be either state or private property.

Latvia is one of the three post-Soviet Baltic states having regained independence in 1991 and since 2004 is a member State of the European Union. After its independence there have been fundamental changes of political, economic and social nature that have turned Latvia into a democratic country with a free market economy. This reflects on the mass media landscape which is considered well-developed despite being subjected to a limited market and a linguistic and cultural split between Latvian (58.2%) and Russian speakers (37.5%). In 2017 Freedom House defined Latvia's press freedom status as “free", assigning to the country's press freedom a score of 26/100. The 2017 World Press Freedom Index prepared annually by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) states that media in Latvia have a "two-speed freedom", underlying different levels of freedom for Latvian-language and Russian-language media. According to RSF's Index the country is ranked 28th among 180 countries.

Human rights in Zambia are addressed in Zambia's constitution. However, the Zambia 2012 Human Rights Report of the United States Department of State noted that in general, the government's human rights record remained poor. The 2021 version of this report noted improvements in many areas.

Dawit Kebede is an Ethiopian journalist who spent 21 months as a political prisoner after criticising his country's government in the lead up to the 2005 general election. He was released on a presidential pardon nearly two years later and sought asylum in the United States in 2011. He returned to Ethiopia in 2014. Dawit was awarded the 2010 CPJ International Press Freedom Award for his dedication to journalism.

Temesgen Desalegn is an Ethiopian journalist. As an editor of the independent weekly newspaper Feteh, Desalegn went to court many times and was imprisoned from 2014 to 2017 as a result of his criticism of the national government, drawing protests on his behalf from the international press freedom groups Committee to Protect Journalists and Article 19 and from Amnesty International. In its 2014 report, the U.S. Department of State also reported its concern against Temsgen's 3 years sentence by the government, emphasizing that Freedom of expression and freedom of the press are fundamental elements of a democratic society and government. The Human Rights Watch also reported his charge in August 2012 and his three years sentence in 2014.

Media freedom in Azerbaijan is severely curtailed. Most Azerbaijanis receive their information from mainstream television, which is unswervingly pro-government and under strict government control. According to a 2012 report of the NGO "Institute for Reporters' Freedom and Safety (IRFS)" Azerbaijani citizens are unable to access objective and reliable news on human rights issues relevant to Azerbaijan and the population is under-informed about matters of public interest.

Freedom of the press in Djibouti is not specifically mentioned by the country's constitution. However, Article 15 of the Constitution of Djibouti does mention an individual's right to express their opinion "...by word, pen, or image..." and notes that "these rights may be limited by prescriptions in the law and in respect for the honour of others."

Laos has one of the most restrictive media environments in the world. In 2020, Reporters Without Borders ranked Laos 172 out of 179 on its annual Press Freedom Index, behind countries such as Cuba and Iran.

Censorship in Bolivia can be traced back through years of conflict between Bolivia's indigenous population and the wealthier population of European descent. Until Bolivia democratized in 1982, the media was strictly controlled.

South Korea is considered to have freedom of the press, but it is subject to several pressures. It has improved since South Korea transitioned to democracy in the late 20th century, but declined slightly in the 2010s. Freedom House Freedom of the Press has classified South Korean press as free from 2002 to 2010, and as partly free since 2011.

Although the Eritrean constitution guarantees freedom of speech and press, Eritrea has been ranked as one of the worst countries in terms of freedom of the press. As of 2004, the press in Eritrea under the government led by Isaias Afwerki remained tightly controlled.

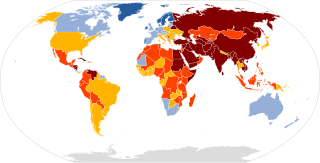

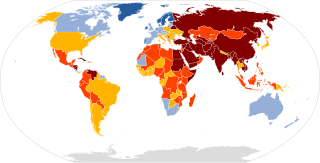

Safety of journalists is the ability of journalists and media professionals to receive, produce and share information without facing physical or moral threats.

Somaliland is a democratic nation in the Horn of Africa. Somaliland has endorsed the freedom of expression and free press since it declared its independence from Somalia. According to Somaliland's constitution and Somaliland media laws, defamation and libel are not criminal offenses; aggrieved parties may seek redress in civil courts.

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance in Africa provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries in Africa.

Freedom of the press in Bangladesh refers to the censorship and endorsement on public opinions, fundamental rights, freedom of expression, human rights, explicitly mass media such as the print, broadcast and online media as described or mentioned in the constitution of Bangladesh. The country's press is legally regulated by the certain amendments, while the sovereignty, national integrity and sentiments are generally protected by the law of Bangladesh to maintain a hybrid legal system for independent journalism and to protect fundamental rights of the citizens in accordance with secularism and media law. In Bangladesh, media bias and disinformation is restricted under the certain constitutional amendments as described by the country's post-independence constitution.

Since the end of the Rwandan Civil War, many forms of censorship have been implemented in Rwanda.