Related Research Articles

Privacy is the ability of an individual or group to seclude themselves or information about themselves, and thereby express themselves selectively.

Consumer privacy is information privacy as it relates to the consumers of products and services.

Information privacy is the relationship between the collection and dissemination of data, technology, the public expectation of privacy, contextual information norms, and the legal and political issues surrounding them. It is also known as data privacy or data protection.

The Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) is a non-departmental public body which reports directly to the Parliament of the United Kingdom and is sponsored by the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology. It is the independent regulatory office dealing with the Data Protection Act 2018 and the General Data Protection Regulation, the Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations 2003 across the UK; and the Freedom of Information Act 2000 and the Environmental Information Regulations 2004 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and, to a limited extent, in Scotland. When they audit an organisation they use Symbiant's audit software.

Data security means protecting digital data, such as those in a database, from destructive forces and from the unwanted actions of unauthorized users, such as a cyberattack or a data breach.

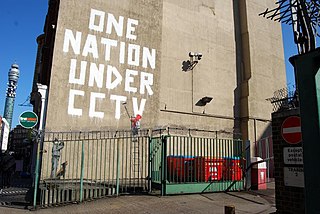

Internet privacy involves the right or mandate of personal privacy concerning the storage, re-purposing, provision to third parties, and display of information pertaining to oneself via the Internet. Internet privacy is a subset of data privacy. Privacy concerns have been articulated from the beginnings of large-scale computer sharing and especially relate to mass surveillance.

A privacy policy is a statement or legal document that discloses some or all of the ways a party gathers, uses, discloses, and manages a customer or client's data. Personal information can be anything that can be used to identify an individual, not limited to the person's name, address, date of birth, marital status, contact information, ID issue, and expiry date, financial records, credit information, medical history, where one travels, and intentions to acquire goods and services. In the case of a business, it is often a statement that declares a party's policy on how it collects, stores, and releases personal information it collects. It informs the client what specific information is collected, and whether it is kept confidential, shared with partners, or sold to other firms or enterprises. Privacy policies typically represent a broader, more generalized treatment, as opposed to data use statements, which tend to be more detailed and specific.

Personal data, also known as personal information or personally identifiable information (PII), is any information related to an identifiable person.

Information privacy, data privacy or data protection laws provide a legal framework on how to obtain, use and store data of natural persons. The various laws around the world describe the rights of natural persons to control who is using its data. This includes usually the right to get details on which data is stored, for what purpose and to request the deletion in case the purpose is not given anymore.

Privacy law is a set of regulations that govern the collection, storage, and utilization of personal information from healthcare, governments, companies, public or private entities, or individuals.

Security breach notification laws or data breach notification laws are laws that require individuals or entities affected by a data breach, unauthorized access to data, to notify their customers and other parties about the breach, as well as take specific steps to remedy the situation based on state legislature. Data breach notification laws have two main goals. The first goal is to allow individuals a chance to mitigate risks against data breaches. The second goal is to promote company incentive to strengthen data security.Together, these goals work to minimize consumer harm from data breaches, including impersonation, fraud, and identity theft.

Privacy by design is an approach to systems engineering initially developed by Ann Cavoukian and formalized in a joint report on privacy-enhancing technologies by a joint team of the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario (Canada), the Dutch Data Protection Authority, and the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research in 1995. The privacy by design framework was published in 2009 and adopted by the International Assembly of Privacy Commissioners and Data Protection Authorities in 2010. Privacy by design calls for privacy to be taken into account throughout the whole engineering process. The concept is an example of value sensitive design, i.e., taking human values into account in a well-defined manner throughout the process.

Do Not Track legislation protects Internet users' right to choose whether or not they want to be tracked by third-party websites. It has been called the online version of "Do Not Call". This type of legislation is supported by privacy advocates and opposed by advertisers and services that use tracking information to personalize web content. Do Not Track (DNT) is a formerly official HTTP header field, designed to allow internet users to opt-out of tracking by websites—which includes the collection of data regarding a user's activity across multiple distinct contexts, and the retention, use, or sharing of that data outside its context. Efforts to standardize Do Not Track by the World Wide Web Consortium did not reach their goal and ended in September 2018 due to insufficient deployment and support.

The General Data Protection Regulation, abbreviated GDPR, or French RGPD is a European Union regulation on information privacy in the European Union (EU) and the European Economic Area (EEA). The GDPR is an important component of EU privacy law and human rights law, in particular Article 8(1) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. It also governs the transfer of personal data outside the EU and EEA. The GDPR's goals are to enhance individuals' control and rights over their personal information and to simplify the regulations for international business. It supersedes the Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC and, among other things, simplifies the terminology.

Chris Jay Hoofnagle is an American professor at the University of California, Berkeley who teaches information privacy law, computer crime law, regulation of online privacy, internet law, and seminars on new technology. Hoofnagle has contributed to the privacy literature by writing privacy law legal reviews and conducting research on the privacy preferences of Americans. Notably, his research demonstrates that most Americans prefer not to be targeted online for advertising and despite claims to the contrary, young people care about privacy and take actions to protect it. Hoofnagle has written scholarly articles regarding identity theft, consumer privacy, U.S. and European privacy laws, and privacy policy suggestions.

Privacy engineering is an emerging field of engineering which aims to provide methodologies, tools, and techniques to ensure systems provide acceptable levels of privacy. Its focus lies in organizing and assessing methods to identify and tackle privacy concerns within the engineering of information systems.

Data re-identification or de-anonymization is the practice of matching anonymous data with publicly available information, or auxiliary data, in order to discover the person to whom the data belongs. This is a concern because companies with privacy policies, health care providers, and financial institutions may release the data they collect after the data has gone through the de-identification process.

The right of access, also referred to as right to access and (data) subject access, is one of the most fundamental rights in data protection laws around the world. For instance, the United States, Singapore, Brazil, and countries in Europe have all developed laws that regulate access to personal data as privacy protection. The European Union states that: "The right of access occupies a central role in EU data protection law's arsenal of data subject empowerment measures." This right is often implemented as a Subject Access Request (SAR) or Data Subject Access Request (DSAR).

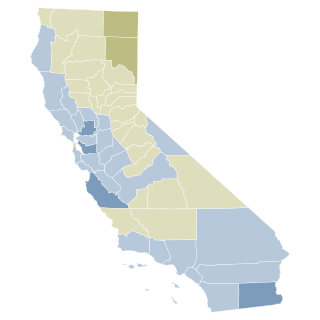

The California Privacy Rights Act of 2020 (CPRA), also known as Proposition 24, is a California ballot proposition that was approved by a majority of voters after appearing on the ballot for the general election on November 3, 2020. This proposition expands California's consumer privacy law and builds upon the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) of 2018, which established a foundation for consumer privacy regulations.

The Personal Information Protection Law of the People's Republic of China referred to as the Personal Information Protection Law or ("PIPL") protecting personal information rights and interests, standardize personal information handling activities, and promote the rational use of personal information. It also addresses the transfer of personal data outside of China.

References

- ↑ Li, Xiao Bai; Motiwalla, Luvai F. (2016). "Unveiling consumers' privacy paradox behavior in an economic exchange". International Journal of Business Information Systems. 23 (3): 307–329. doi:10.1504/IJBIS.2016.10000351. PMC 5046831 . PMID 27708687.

- ↑ "Cybersecurity Incidents". U.S. Office of Personnel Management.

- ↑ Milne, George R.; Pettinico, George; Hajjat, Fatima M.; Markos, Ereni (March 2017). "Information Sensitivity Typology: Mapping the Degree and Type of Risk Consumers Perceive in Personal Data Sharing". Journal of Consumer Affairs. 51 (1): 133–161. doi:10.1111/joca.12111. hdl: 10.1111/joca.12111 .

- ↑ Cappello, Lawrence (December 15, 2016). "Big Iron and the Small Government: On the History of Data Collection and Privacy in the United States". Journal of Policy History. 29 (1): 177–196. doi:10.1017/S0898030616000397.

- ↑ Li, Xiao Bai; Motiwalla, Luvai F. (2016). "Unveiling consumers' privacy paradox behavior in an economic exchange". International Journal of Business Information Systems. 23 (3): 307–329. doi:10.1504/IJBIS.2016.10000351. PMC 5046831 . PMID 27708687.

- ↑ Cappello, Lawrence (December 15, 2016). "Big Iron and the Small Government: On the History of Data Collection and Privacy in the United States". Journal of Policy History. 29 (1): 177–196. doi:10.1017/S0898030616000397.

- ↑ Taylor, Isaac (2017). "Data collection, counterterrorism and the right to privacy". Politics, Philosophy & Economics. 16 (3): 326–346. doi:10.1177/1470594x17715249.

- ↑ ZENG, JINGHAN (November 2016). "China's date with big data: will it strengthen or threaten authoritarian rule?". International Affairs. 92 (6): 1443–1462. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12750.

- ↑ ZENG, JINGHAN (November 2016). "China's date with big data: will it strengthen or threaten authoritarian rule?". International Affairs. 92 (6): 1443–1462. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12750.

- ↑ Mikkonen, Tomi (April 1, 2014). "Perceptions of controllers on EU data protection reform: A Finnish perspective". Computer Law & Security Review. 30 (2): 190–195. doi:10.1016/j.clsr.2014.01.011. ISSN 0267-3649.

- ↑ Mikkonen, Tomi (April 1, 2014). "Perceptions of controllers on EU data protection reform: A Finnish perspective". Computer Law & Security Review. 30 (2): 190–195. doi:10.1016/j.clsr.2014.01.011. ISSN 0267-3649.

- ↑ "Privacy considerations of online behavioral tracking". European Union Agency for Network and Information Security.

- ↑ Solon, Olivia (April 4, 2018). "Facebook says Cambridge Analytica may have gained 37m more users' data". the Guardian.

- ↑ "A Comparison Between US and EU Data Protection Legislation for Law Enforcement Purposes - Think Tank". www.europarl.europa.eu.

- ↑ ZENG, JINGHAN (November 2016). "China's date with big data: will it strengthen or threaten authoritarian rule?". International Affairs. 92 (6): 1443–1462. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12750.

- ↑ "Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons about the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) (Text with EEA relevance)". May 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Privacy & Data Security Update (2016)". Federal Trade Commission. January 18, 2017.

- ↑ "LifeLock to Pay $100 Million to Consumers to Settle FTC Charges it Violated 2010 Order". Federal Trade Commission. December 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Online Behavioral Advertising: Moving the Discussion Forward to Possible Self-Regulatory Principles: Statement of the Bureau of Consumer Protection Proposing Governing Principles For Online Behavioral Advertising and Requesting Comment". Federal Trade Commission. January 16, 2014. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Facebook Users' Privacy Concerns Up Since 2011". Gallup.

- ↑ "The Spotlight's on Facebook, but Google Is Also in the Privacy Hot Seat". NDTV Gadgets360.com.

- ↑ Milne, George R.; Pettinico, George; Hajjat, Fatima M.; Markos, Ereni (March 2017). "Information Sensitivity Typology: Mapping the Degree and Type of Risk Consumers Perceive in Personal Data Sharing". Journal of Consumer Affairs. 51 (1): 133–161. doi:10.1111/joca.12111. hdl: 10.1111/joca.12111 .