The president of the Council of Ministers of the Italian Republic, commonly referred to in Italy as Presidente del Consiglio or informally as Premier, and known in English as the prime minister of Italy, is the head of government of the Italian Republic. The office of Prime Minister is established by Articles 92 through 96 of the Constitution of Italy. The prime minister is appointed by the president of the Republic and must have the confidence of the Italian Parliament to stay in office.

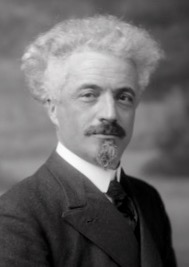

Gaetano Salvemini was an Italian Socialist and antifascist politician, historian and writer. Born in a family of modest means, he became an acclaimed historian both in Italy and abroad, particularly in the United States, after he was forced into exile by Mussolini's fascist regime.

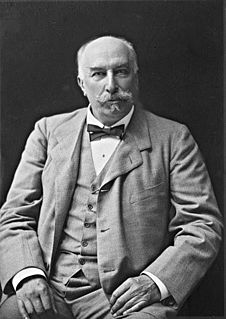

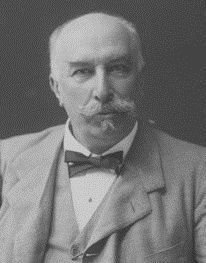

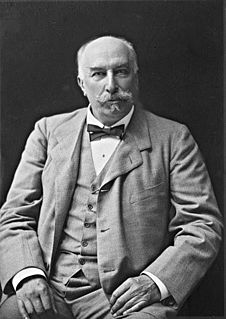

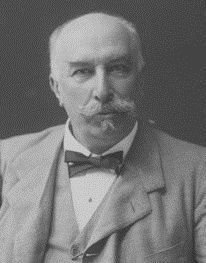

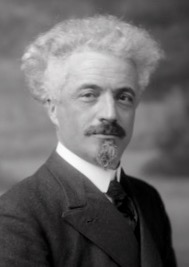

Giovanni Giolitti was an Italian statesman. He was the Prime Minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. After Benito Mussolini, he is the second-longest serving Prime Minister in Italian history. A prominent leader of the Historical Left and the Liberal Union, he is widely considered one of the most powerful and important politicians in Italian history; due to his dominant position in Italian politics, Giolitti was accused by critics of being an authoritarian leader and a parliamentary dictator.

Clerical fascism is an ideology that combines the political and economic doctrines of fascism with clericalism. The term has been used to describe organizations and movements that combine religious elements with fascism, receive support from religious organizations which espouse sympathy for fascism, or fascist regimes in which clergy play a leading role.

The March on Rome was an organized mass demonstration and a coup d'état in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 1922, Fascist Party leaders planned an insurrection, to take place on 28 October. When fascist demonstrators and Blackshirt paramilitaries entered Rome, Prime Minister Luigi Facta wished to declare a state of siege, but this was overruled by King Victor Emmanuel III. On the following day, 29 October 1922, the King appointed Mussolini as Prime Minister, thereby transferring political power to the fascists without armed conflict.

Liberalism and radicalism have played a role in the political history of Italy since the country's unification, started in 1861 and largely completed in 1871, and currently influence several leading political parties.

This articles covers the history of Italy as a monarchy and in the World Wars.

The Azione Cattolica Italiana, or Azione Cattolica for short, is a widespread Roman Catholic lay association in Italy.

The Kingdom of Italy was a state that existed from 1861—when King Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy—until 1946, when civil discontent led an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and form the modern Italian Republic. The state was founded as a result of the Risorgimento under the influence of the Savoy-led Kingdom of Sardinia, which can be considered its legal predecessor state.

General elections were held in Italy on 26 October 1913, with a second round of voting on 2 November. The Liberals narrowly retained an absolute majority in the Chamber of Deputies, while the Radical Party emerged as the largest opposition bloc. Both groupings did particularly well in Southern Italy, while the Italian Socialist Party gained eight seats and was the largest party in Emilia-Romagna. However, the election marked the beginning of the decline of Liberal establishment.

Count Vincenzo Ottorino Gentiloni was an Italian politician, one of the early leaders of the Italian Catholic Azione Cattolica movement. He was born near Ancona, was active in Catholic politics from the 1890s, and served as president of the Catholic Electoral Union from 1909 to 1916.

The Italian Catholic Electoral Union was a political organization designed to coordinate the participation of Catholic voices in Italian electoral contests. Its founder and leader was the Count Vincenzo Ottorino Gentiloni.

The Right group, later called Historical Right by historians to distinguish it from the right-wing groups of the 20th century, was an Italian conservative parliamentary group during the second half of the 19th century. After 1876, the Historical Right constituted the Constitutional opposition toward the left governments. It originated in the convergence of the most liberal faction of the moderate right and the moderate wing of the democratic left. The party included men from heterogeneous cultural, class, and ideological backgrounds, ranging from Anglo-Saxon individualist liberalism to Neo-Hegelian liberalism as well as liberal-conservatives, from strict secularists to more religiously-oriented reformists. Few prime ministers after 1852 were party men; instead they accepted support where they could find it, and even the governments of the Historical Right during the 1860s included leftists in some capacity.

The Left group, later called Historical Left by historians to distinguish it from the left-wing groups of the 20th century, was a liberal and reformist parliamentary group in Italy during the second half of the 19th century. The members of the Left were also known as Democrats or Ministerials. The Left was the dominant political group in the Kingdom of Italy from the 1870s until its dissolution in the early 1910s.

The Liberal Union, simply and collectively called Liberals, was a political alliance formed in the first years of the 20th century by the Italian Prime Minister and leader of the Historical Left Giovanni Giolitti. The alliance was formed when the Left and the Right merged in a single centrist and liberal coalition which largely dominated the Italian Parliament.

Events from the year 1903 in Italy.

Events from the year 1913 in Italy.

Events from the year 1921 in Italy.

Marcello Soleri was an Italian politician and an officer of the prestigious Alpini infantry corps. He is widely viewed as one of the leading exponents of political liberalism in twentieth century Italy. Soleri was a Member of Parliament between 1913 and 1929. During 1921/22 he served successively as Italian Minister of Finance and as Italian Minister of War. After the fall of Mussolini he returned to government in 1944 as Italian Minister of Treasury under Prime Minister Bonomi.

Tancredi Galimberti was an Italian politician during the first part of the twentieth century. He served as Minister for Postal and Telegraphic communications in the Zanardelli government between 1901 and 1903. In 1929, despite being openly equivocal about the leader's post-democratic approach to politics, he was appointed to the senate.