Related Research Articles

A disaster is an event that causes serious harm to people, buildings, economies, or the environment, and the affected community cannot handle it alone. Natural disasters like avalanches, floods, earthquakes, and wildfires are caused by natural hazards. Human-made disasters like oil spills, terrorist attacks and power outages are caused by people. Nowadays, it is hard to separate natural and human-made disasters because human actions can make natural disasters worse. Climate change also affects how often disasters due to extreme weather hazards happen.

A natural disaster is the very harmful impact on a society or community after a natural hazard event. Some examples of natural hazard events include avalanches, droughts, earthquakes, floods, heat waves, landslides, tropical cyclones, volcanic activity and wildfires. Additional natural hazards include blizzards, dust storms, firestorms, hails, ice storms, sinkholes, thunderstorms, tornadoes and tsunamis. A natural disaster can cause loss of life or damage property. It typically causes economic damage. How bad the damage is depends on how well people are prepared for disasters and how strong the buildings, roads, and other structures are. Scholars have been saying that the term natural disaster is unsuitable and should be abandoned. Instead, the simpler term disaster could be used. At the same time the type of hazard would be specified. A disaster happens when a natural or human-made hazard impacts a vulnerable community. It results from the combination of the hazard and the exposure of a vulnerable society.

The Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA) is an inter-regional supportive network of independent emergency units throughout the Caribbean region. Formed on September 1, 2005, as the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Response Agency (CDERA), it underwent a name change to CDEMA in September 2009.

A humanitarian crisis is defined as a singular event or a series of events that are threatening in terms of health, safety or well-being of a community or large group of people. It may be an internal or external conflict and usually occurs throughout a large land area. Local, national and international responses are necessary in such events.

The World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction is a series of United Nations conferences focusing on disaster and climate risk management in the context of sustainable development. The World Conference has been convened three times, with each edition to date having been hosted by Japan: in Yokohama in 1994, in Hyogo in 2005 and in Sendai in 2015. As requested by the UN General Assembly, the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) served as the coordinating body for the Second and Third UN World Conference on Disaster Reduction in 2005 and 2015.

Emergency management is a science and a system charged with creating the framework within which communities reduce vulnerability to hazards and cope with disasters. Emergency management, despite its name, does not actually focus on the management of emergencies; emergency management or disaster management can be understood as minor events with limited impacts and are managed through the day-to-day functions of a community. Instead, emergency management focuses on the management of disasters, which are events that produce more impacts than a community can handle on its own. The management of disasters tends to require some combination of activity from individuals and households, organizations, local, and/or higher levels of government. Although many different terminologies exist globally, the activities of emergency management can be generally categorized into preparedness, response, mitigation, and recovery, although other terms such as disaster risk reduction and prevention are also common. The outcome of emergency management is to prevent disasters and where this is not possible, to reduce their harmful impacts.

Brian E. Tucker is an American seismologist specializing in disaster prevention. He is also the founder of GeoHazards International (GHI), a non-profit dedicated to ending preventable death and suffering caused by natural disasters in the world’s most vulnerable communities.

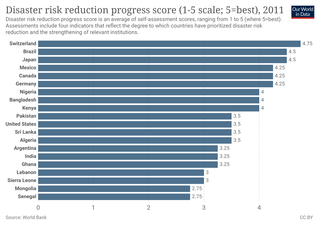

Disaster risk reduction aims to make disasters less likely to happen. The approach, also called DRR or disaster risk management, also aims to make disasters less damaging when they do occur. DRR aims to make communities stronger and better prepared to handle disasters. In technical terms, it aims to make them more resilient or less vulnerable. When DRR is successful, it makes communities less the vulnerable because it mitigates the effects of disasters. This means DRR can make risky events fewer and less severe. Climate change can increase climate hazards. So development efforts often consider DRR and climate change adaptation together.

The EUR-OPA Major Hazards Agreement is a Partial Agreement of the Council of Europe, set up in 1987 by Resolution (87) 2 of the Committee of Ministers. Its full name is "Co-operation Group for the Prevention of, Protection Against, and Organisation of Relief in Major Natural and Technological Disasters (EUR-OPA)".

The 1988 Nepal earthquake occurred near the Nepal–India border on 20 August 1988 at 23:09:09 UTC. The epicenter was located in Udayapur District. Measuring Mw 6.9, it was the largest earthquake recorded in the country since 1934.

The Emergency Capacity Building Project is a collaborative capacity-building project aimed at improving the speed, effectiveness and delivery of humanitarian response programs. The ECB Project is a partnership between seven non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and implements programs in one region and four countries known as consortia.

The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) was created in December 1999 to ensure the implementation of the International Strategy for Disaster Reduction.

The National Society for Earthquake Technology – Nepal (NSET) is a Nepali non-governmental organization working on reducing earthquake risk and increasing earthquake preparedness in Nepal as well as other earthquake-prone countries.

Disaster preparedness in museums, galleries, libraries, archives and private collections, involves any actions taken to plan for, prevent, respond or recover from natural disasters and other events that can cause damage or loss to cultural property. 'Disasters' in this context may include large-scale natural events such as earthquakes, flooding or bushfire, as well as human-caused events such as theft and vandalism. Increasingly, anthropogenic climate change is a factor in cultural heritage disaster planning, due to rising sea levels, changes in rainfall patterns, warming average temperatures, and more frequent extreme weather events.

The Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) was an organizational unit within the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) charged by the President of the United States with directing and coordinating international United States government disaster assistance. USAID merged the former offices of OFDA and Food for Peace (FFP) in 2020 to form the Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (BHA).

School Safety Preparedness Drill (SSPD) is an annual earthquake preparedness drill being organised in schools of North and North Eastern states of India commemorating 4 April 1905 Kangra earthquake.

The 2016 Imphal earthquake occurred on 4 January 2016 at 4:35 a.m. local time in Manipur, and had a magnitude of 6.7 Mw. The seismic wave radius travelled over 200 km and shaking was felt in numerous cities, including Imphal, Silchar and Guwahati. 13 people in India and Bangladesh were killed, and many buildings in the city of Imphal and surrounding areas were damaged.

A safety drill is a drill that is practised to prepare people for an emergency.

Common Operational Datasets or CODs, are authoritative reference datasets needed to support operations and decision-making for all actors in a humanitarian response. CODs are 'best available' datasets that ensure consistency and simplify the discovery and exchange of key data. The data is typically geo-spatially linked using a coordinate system and has unique geographic identification codes (P-codes).

The Asian Disaster Preparedness Center (ADPC) is an autonomous, regional organization established to strengthen disaster risk reduction (DRR) and climate resilience in Asia and the Pacific. Founded in 1986 and headquartered in Bangkok, Thailand, ADPC provides technical assistance, capacity building, research, and policy support to governments, international organizations, and communities.

References

- ↑ "Our Mission". GeoHazards International. Archived from the original on 4 August 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Our Approach". GeoHazards International. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Our Projects". GeoHazards International. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ Peterson, Greg (4 October 2002). "Seismologist wins 'Genius Grant'". GeoTimes. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "The People We Serve". GeoHazards International. Archived from the original on 30 August 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ Showstack, Randy (7 May 2015). "Reducing Earthquake Risk in Nepal". Eos: Earth & Space Science News. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Our Approach". GeoHazards International. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "GeoHazards Society India". GeoHazards Society India. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "NSET History/Archives". NSET-Nepal. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ Showstack, Randy (7 May 2015). "Reducing Earthquake Risk in Nepal". Eos: Earth & Space Science News. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Earthquake Safety Day". NSET-Nepal. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Event Highlights". NSET-Nepal. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "School Safety". GeoHazards Society. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "School Safety Initiatives completed by GeoHazards Society" (PDF). GeoHazards Society. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Framed Infill Network". GeoHazards International. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Thornton Tomasetti Foundation Announces GeoHazards International Grant". Thornton Tomasetti Foundation. 25 June 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Developing Guidance on Protective Actions to Take During Earthquakes". GeoHazards International. June 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Our Funding Partners". GeoHazards International. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Natural and Technological Risks: Geological Hazards Update: Highlights of Fiscal Year (FY) 2014 Activities" (PDF). USAID. October 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Project Completion Report of the Kathmandu Valley Earthquake Risk Management Project" (PDF). USAID. September 2000. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Saving more than 100,000 lives through a simple, innovative solution: Tsunami Evacuation Raised Earth Park". Swiss Re. 30 September 2010. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Improving hospital earthquake safety in India". Swiss Re. March 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Prevention and adaptation measures: Natural disaster prevention project in India". Munich Re. Archived from the original on 18 July 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ Showstack, Randy (5 May 2015). "What Can We Learn About Disaster Preparedness from Nepal's Quake?". Eos: Earth & Space Science News. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ Rai, Bhrikuti (28 April 2015). "Scientists warned of ageing risk maps before Nepal quake". PreventionWeb. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ Borenstein, Seth (25 April 2015). "Nepal Earthquake Was Disaster Experts Knew Was Coming". HuffingtonPost.com, Inc. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Post-earthquake Reconstruction in Nepal". GeoHazards International. 6 May 2015. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Nepal devastation a 'wake-up call' for vulnerable region". The Japan Times. 6 May 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.