Related Research Articles

Conjunctivitis, also known as pink eye, is inflammation of the outermost layer of the white part of the eye and the inner surface of the eyelid. It makes the eye appear pink or reddish. Pain, burning, scratchiness, or itchiness may occur. The affected eye may have increased tears or be "stuck shut" in the morning. Swelling of the white part of the eye may also occur. Itching is more common in cases due to allergies. Conjunctivitis can affect one or both eyes.

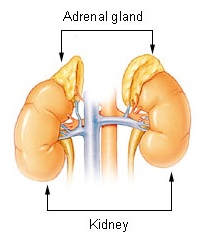

Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome (WFS) is defined as adrenal gland failure due to bleeding into the adrenal glands, commonly caused by severe bacterial infection. Typically, it is caused by Neisseria meningitidis.

Pharyngitis is inflammation of the back of the throat, known as the pharynx. It typically results in a sore throat and fever. Other symptoms may include a runny nose, cough, headache, difficulty swallowing, swollen lymph nodes, and a hoarse voice. Symptoms usually last 3–5 days, but can be longer depending on cause. Complications can include sinusitis and acute otitis media. Pharyngitis is a type of upper respiratory tract infection.

Sputum is mucus that is coughed up from the lower airways. In medicine, sputum samples are usually used for a naked eye examination, microbiological investigation of respiratory infections and cytological investigations of respiratory systems. It is crucial that the specimen does not include any mucoid material from the nose or oral cavity.

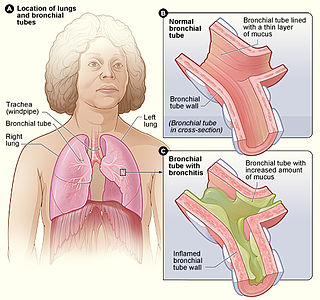

Acute bronchitis, also known as a chest cold, is short-term bronchitis – inflammation of the bronchi of the lungs. The most common symptom is a cough. Other symptoms include coughing up mucus, wheezing, shortness of breath, fever, and chest discomfort. The infection may last from a few to ten days. The cough may persist for several weeks afterward with the total duration of symptoms usually around three weeks. Some have symptoms for up to six weeks.

The HACEK organisms are a group of fastidious Gram-negative bacteria that are an unusual cause of infective endocarditis, which is an inflammation of the heart due to bacterial infection. HACEK is an abbreviation of the initials of the genera of this group of bacteria: Haemophilus, Aggregatibacter, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, Kingella. The HACEK organisms are a normal part of the human microbiota, living in the oral-pharyngeal region.

An upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) is an illness caused by an acute infection, which involves the upper respiratory tract, including the nose, sinuses, pharynx, larynx or trachea. This commonly includes nasal obstruction, sore throat, tonsillitis, pharyngitis, laryngitis, sinusitis, otitis media, and the common cold. Most infections are viral in nature, and in other instances, the cause is bacterial. URTIs can also be fungal or helminthic in origin, but these are less common.

Haemophilus influenzae is a Gram-negative, non-motile, coccobacillary, facultatively anaerobic, capnophilic pathogenic bacterium of the family Pasteurellaceae. The bacteria are mesophilic and grow best at temperatures between 35 and 37 °C.

Lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) is a term often used as a synonym for pneumonia but can also be applied to other types of infection including lung abscess and acute bronchitis. Symptoms include shortness of breath, weakness, fever, coughing and fatigue. A routine chest X-ray is not always necessary for people who have symptoms of a lower respiratory tract infection.

Bacterial pneumonia is a type of pneumonia caused by bacterial infection.

Epiglottitis is the inflammation of the epiglottis—the flap at the base of the tongue that prevents food entering the trachea (windpipe). Symptoms are usually rapid in onset and include trouble swallowing which can result in drooling, changes to the voice, fever, and an increased breathing rate. As the epiglottis is in the upper airway, swelling can interfere with breathing. People may lean forward in an effort to open the airway. As the condition worsens, stridor and bluish skin may occur.

Mastoiditis is the result of an infection that extends to the air cells of the skull behind the ear. Specifically, it is an inflammation of the mucosal lining of the mastoid antrum and mastoid air cell system inside the mastoid process. The mastoid process is the portion of the temporal bone of the skull that is behind the ear. The mastoid process contains open, air-containing spaces. Mastoiditis is usually caused by untreated acute otitis media and used to be a leading cause of child mortality. With the development of antibiotics, however, mastoiditis has become quite rare in developed countries where surgical treatment is now much less frequent and more conservative, unlike former times.

Brazilian purpuric fever (BPF) is an illness of children caused by the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius which is ultimately fatal due to sepsis. BPF was first recognized in the São Paulo state of Brazil in 1984. At this time, young children between the ages of 3 months and 10 years were contracting a strange illness which was characterized by high fever and purpuric lesions on the body. These cases were all fatal, and originally thought to be due to meningitis. It was not until the autopsies were conducted that the cause of these deaths was confirmed to be infection by H. influenzae aegyptius. Although BPF was thought to be confined to Brazil, other cases occurred in Australia and the United States during 1984–1990.

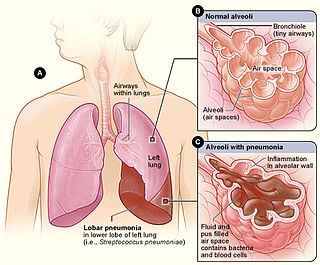

Lobar pneumonia is a form of pneumonia characterized by inflammatory exudate within the intra-alveolar space resulting in consolidation that affects a large and continuous area of the lobe of a lung.

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) or nosocomial pneumonia refers to any pneumonia contracted by a patient in a hospital at least 48–72 hours after being admitted. It is thus distinguished from community-acquired pneumonia. It is usually caused by a bacterial infection, rather than a virus.

Adenoiditis is the inflammation of the adenoid tissue usually caused by an infection. Adenoiditis is treated using medication or surgical intervention.

Haemophilus meningitis is a form of bacterial meningitis caused by the Haemophilus influenzae bacteria. It is usually associated with Haemophilus influenzae type b. Meningitis involves the inflammation of the protective membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord. Haemophilus meningitis is characterized by symptoms including fever, nausea, sensitivity to light, headaches, stiff neck, anorexia, and seizures. Haemophilus meningitis can be deadly, but antibiotics are effective in treating the infection, especially when cases are caught early enough that the inflammation has not done a great deal of damage. Before the introduction of the Hib vaccine in 1985, Haemophilus meningitis was the leading cause of bacterial meningitis in children under the age of five. However, since the creation of the Hib vaccine, only two in every 100,000 children contract this type of meningitis. Five to ten percent of cases can be fatal, although the average mortality rate in developing nations is seventeen percent, mostly due to lack of access to vaccination as well as lack of access to medical care needed to combat the meningitis.

An acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis (AECB), is a sudden worsening of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) symptoms including shortness of breath, quantity and color of phlegm that typically lasts for several days.

Haemophilus haemolyticus is a species of gram-negative bacteria that is related to Haemophilus influenzae. H. haemolyticus is generally nonpathogenic, however there have been two cases of H.haemolyticus causing endocarditis.

Janet Gilsdorf is an American pediatric infectious diseases physician, scientist, and writer at the University of Michigan. Her research has focused on the pathogenic, molecular, and epidemiologic features of the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae. She served as the Director of the Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases in the University of Michigan Health System from 1989 to 2012 and Co-Director of the Center for Molecular and Clinical Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases at the School of Public Health at the University of Michigan from 2000 – 2015. In addition to her scientific publications, she is also the author of two novels, one memoir, one non-fiction book, and a number of medically-oriented essays.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Harrison, Lee H. et al. “Epidemiology and Clinical Spectrum of Brazilian Purpuric Fever,” Journal of Clinical Microbiology 27, no. 4 (1989): 599–604.

- ↑ Weeks, J.E. “The bacillus of acute conjunctival catarrh, or ‘pink eye’.” Archive Ophthalmology 15 (1886): 441–51.

- ↑ Pittman, Margaret and Dorland J. Davis. “Identification of the Koch-Weeks bacillus (hemophilus aegyptius),” Journal of Bacteriology 3, no. 59 (1949): 413–426.

- ↑ Brenner, Don J. et al. “Biochemical, Genetic and Epidemiologic Characterization of Haemophilus influenzae Biogroup Aegyptius (Haemophilus aegyptius) Strains Associated with Brazilian Purpuric Fever,” Journal of Clinical Microbiology 8, no. 26 (1988): 1524–1534.

- ↑ Casin, I, et al. “Deoxyribonucleic acid relatedness between Haemophilus aegyptius and Haemophilus influenzae,” Elsevier, 137B (1986): 155–163.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “International Notes Brazilian Purpuric Fever: Haemophilus aegyptius Bacteremia Complicating Purulent Conjunctivitis.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 35, no. 35 (1986): 553–4.

- ↑ Brazilian Purpuric Fever Study Group. “Brazilian purpuric fever: epidemic purpura fulminans associated with antecedent purulent conjunctivitis.” Lancet ii (1987): 757–61.

- ↑ Brazilian Purpuric Fever Study Group. “Haemophilus aegyptius bacteremia in Brazilian purpuric fever.” Lancet ii (1987): 761–3.