Iwi are the largest social units in New Zealand Māori society. In Māori, iwi roughly means 'people' or 'nation', and is often translated as "tribe," or "a confederation of tribes." The word is both singular and plural in the Māori language, and is typically pluralised as such in English.

The Musket Wars were a series of as many as 3,000 battles and raids fought throughout New Zealand among Māori between 1806 and 1845, after Māori first obtained muskets and then engaged in an intertribal arms race in order to gain territory or seek revenge for past defeats. The battles resulted in the deaths of between 20,000 and 40,000 people and the enslavement of tens of thousands of Māori and significantly altered the rohe, or tribal territorial boundaries, before the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. The Musket Wars reached their peak in the 1830s, with smaller conflicts between iwi continuing until the mid 1840s; some historians argue the New Zealand Wars were a continuation of the Musket Wars. The increased use of muskets in intertribal warfare led to changes in the design of pā fortifications, which later benefited Māori when engaged in battles with colonial forces during the New Zealand Wars.

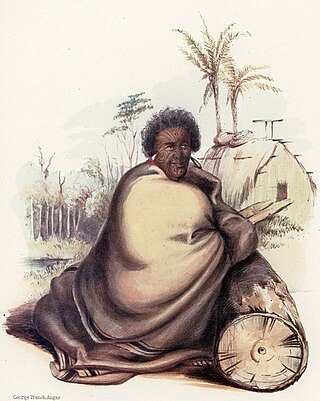

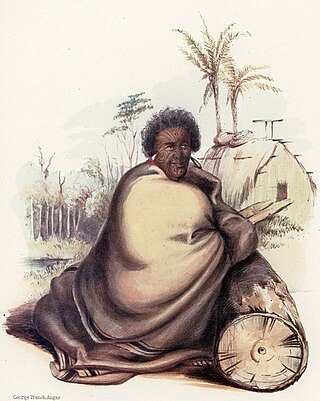

Pōtatau Te Wherowhero was a Māori warrior, leader of the Waikato iwi, the first Māori King and founder of the Te Wherowhero royal dynasty. He was first known just as Te Wherowhero and took the name Pōtatau after he became king in 1858. As disputes over land grew more severe Te Wherowhero found himself increasingly at odds with the Government and its policies.

Arawa was one of the great ocean-going, voyaging canoes in Māori traditions that was used in the migrations that settled New Zealand.

The Human Rights Commission is the national human rights institution (NHRI) for New Zealand. It operates as an independent Crown entity, and is independent from direction by the Cabinet.

Ngāti Ruanui is a Māori iwi traditionally based in the Taranaki region of New Zealand. In the 2006 census, 7,035 people claimed affiliation to the iwi. However, most members now live outside the traditional areas of the iwi.

Ngā Rauru is a Māori iwi in the South Taranaki region of New Zealand. In the 2006 census, 4,047 Māori claimed affiliation to Ngā Rauru, representing 12 hapū.

Ngāti Hauā is a Māori iwi of the eastern Waikato of New Zealand. It is part of the Tainui confederation. Its traditional area includes Matamata, Cambridge, Maungakawa, the Horotiu district along the Waikato River and the Maungatautari district, and its eastern boundary is the Kaimai Range. Leaders of the tribe have included Te Waharoa, his son Wiremu Tamihana and Tamihana's son Tupu Taingakawa. The tribe has played a prominent role in the Māori King Movement, with Tamihana and descendants being known as the "Kingmakers".

The New Zealand Māori Arts and Crafts Institute (NZMACI) is an indigenous traditional art school located in Rotorua New Zealand. It operates the national schools of three major Māori art forms.

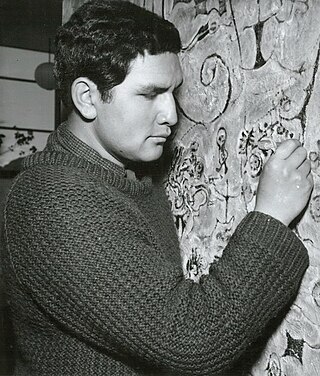

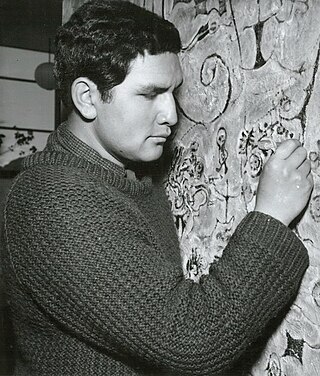

Toi whakairo or just whakairo (carving) is a Māori traditional art of carving in wood, stone or bone.

Diggeress Rangituatahi Te Kanawa was a New Zealand Māori tohunga raranga of Ngāti Maniapoto and Ngāti Kinohaku descent. At the time of her death she was regarded as New Zealand's most renowned weaver.

Sir Charles Moihi Te Arawaka Bennett was a New Zealand broadcaster, military leader, public servant, and high commissioner to the Federation of Malaya (1959–1963). Of Māori descent, he identified with the Ngati Pikiao and Ngati Whakaue iwi.

Te Whakaruruhau o Ngā Reo Irirangi Māori is a New Zealand radio network consisting of radio stations that serve the country's indigenous Māori population. Most stations receive contestable government funding from Te Māngai Pāho, the Māori Broadcast Funding Agency, to operate on behalf of affiliated iwi (tribes) or hapū (sub-tribes). Under their funding agreement, the stations must produce programmes in the Māori language, and must actively promote Māori culture.

Karl Rangikawhiti Leonard is a New Zealand carver and weaver of Te Arawa, Ngāti Awa and Ngāti Raukawa descent. He was the first man elected to the committee of the national Māori weavers' collective, Te Roopu Raranga Whatu o Aotearoa.

Anne Anituatua Delamere was a New Zealand public servant.

Sir Noble Thomson "Toby" Curtis was a New Zealand educator and Māori leader.

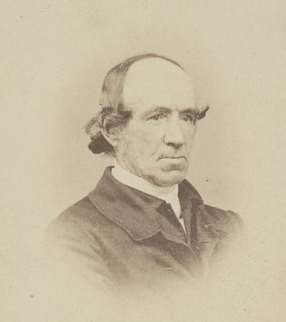

John Whiteley was a missionary for the Wesleyan Missionary Society (WMS) in New Zealand, active from his arrival in the country in 1833 up until his death.

Selwyn Frederick Muru, also known as Herewini Murupaenga, was a New Zealand artist. Of Māori descent, his life's work included painting, sculpture, journalism, broadcasting, directing, acting, set design, theatre, poetry, and whaikōrero. Muru was awarded the Te Tohu Aroha mō Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu | Exemplary/Supreme Award in 1990 at the Creative New Zealand Te Waka Awards.

Ross Calman is a New Zealand Māori writer, editor, historian, and translator of the Māori language.