Transport in Chile is mostly by road. The far south of the country is not directly connected to central Chile by road without travelling through Argentina, and water transport also plays a part there. The railways were historically important in Chile, but now play a relatively small part in the country's transport system. Because of the country's geography and long distances between major cities, aviation is also important.

A mountain railway is a railway that operates in a mountainous region. It may operate through the mountains by following mountain valleys and tunneling beneath mountain passes, or it may climb a mountain to provide transport to and from the summit.

The Trans-Andean railways provide rail transport over the Andes. Several are either planned, built, defunct, or waiting to be restored. They are listed here in order from north to south.

Empresa de los Ferrocarriles del Estado is the national railway and the oldest state-run enterprise in Chile. It manages the infrastructure and operating rail services in the country.

Rail transport in Peru has a varied history. Peruvian rail transport has never formed a true network, primarily comprising separate lines running inland from the coast and built according to freight need rather than passenger need.

The Transandine Railway was a 1,000 mmmetre gauge combined rack and adhesion railway which operated from Mendoza in Argentina, across the Andes mountain range via the Uspallata Pass, to Santa Rosa de Los Andes in Chile, a distance of 248 km.

The Ferrocarril de Antofagasta a Bolivia is a private railway operating in the northern provinces of Chile. It is notable in that it was one of the earliest railways built to 2 ft 6 in narrow gauge, with a route that climbed from sea level to over 4,500 m (14,764 ft), while handling goods traffic totaling near 2 million tons per annum. It proved that a railway with such a narrow gauge could do the work of a standard gauge railway, and influenced the construction of other railways such as the Estrada de Ferro Oeste de Minas. It was later converted to 1,000 mmmetre gauge, and still operates today.

The Metropolitan Archdiocese of Santiago de Chile is one of the five Latin metropolitan sees of the Catholic Church in Chile.

Ferrocarriles Patagónicos was an Argentine State-owned railway company that built and operated several rail lines in Patagonia region. FP were part of the Argentine State Railway created in 1909 during the presidency of José Figueroa Alcorta.

The Bolivian rail network has had a peculiar development throughout its history.

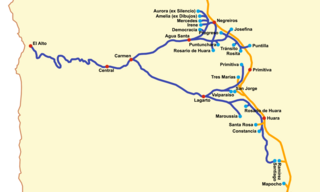

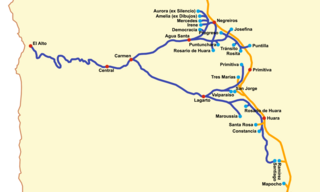

The Arica–La Paz railway or Ferrocarril de Arica–La Paz (FCALP) was built by the Chilean government under the Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1904 between Chile and Bolivia. The railway line was inaugurated on 13 May 1913 and is the shortest line from the Pacific Coast to Bolivia. It is 440 km (273 mi) long, of which 233 km (145 mi) is in Bolivian territory. The Railway is meter gauged. Until 1968, it was rack worked over a 43 km section, on the Chilean side, between Central and Puquios. The line reaches a height of 4257 meters above sea level at General Lagos. The Chile - Bolivia border is crossed between the stations of Visviri and Charaña. When the railway is in operation, it is used for the export of Bolivian minerals and some agricultural production as well as the import of merchandise into Bolivia.

This is an order of battle of the Chilean Army.

The most common track gauge in Chile is the Indian gauge 1,676 mm. In the north there is also some 1,000 mm, metre gauge, rail track.

The Salta–Antofagasta railway, also named Huaytiquina, is a non-electrified single track railway line that links Argentina and Chile passing through the Andes. It is a 1,000 mmmetre gauge railway with a total length of 941 km, connecting the city of Salta (Argentina) to the one of Antofagasta (Chile), on the Pacific Ocean, passing through the Puna de Atacama and Atacama Desert.

In Spain there is an extensive 1,250 km (780 mi) system of 1,000 mmmetre gauge railways. The majority of these railways was historically operated by FEVE,. Created in 1965 FEVE started absorbing numerous private-owned narrow-gauge railways. From 1978 onwards, with the introduction of regionalisation devolution under the new Spanish constitution, FEVE began transferring responsibility for a number of its operations to the new regional governments. On 31 December 2012 the company disappeared due to the merger of the narrow-gauge network FEVE and the broad-gauge network Renfe.

The history of rail transport in Bolivia began in the 1870s after almost three decades of failed efforts to build railroads to integrate the country, mining was the driving force for the construction of railways. The need to transport saltpeter to the coast triggered the first railway lines in Bolivia. It was the silver mining, however, that drove the construction of a railway from the Pacific coast to the high plateau during the nineteenth century. Later, at the beginning of the twentieth century, tin mining gave a new impetus to railway building, forming what is now known as the Andean or Western network. The eastern network, on the other hand, developed between the years 1940 and 1960 and is financed in exchange for oil through agreements with Argentina and Brazil. Bolivia being a landlocked country, the railways played a fundamental role and the history of its railroads is the history of the country's efforts to reach first ports on the Pacific coast and then the Atlantic.

The María-Elena - Tocopilla line was the last operating nitrate railway in Chile, and the last operating section of a railway system that moved caliche ore to processing plants and nitrate to the port of Tocopilla. It was a magnet for rail fans before closing in August 2015 after severe rainfall damaged the tracks to the extent that the owner decided it was beyond economic repair.

The Ferrocarril de Agua Santa was a railway line in the old province of Tarapacá in Chile between 1890 and 1931.