Discrimination is the process of making unfair or prejudicial distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong, such as race, gender, age, religion, physical attractiveness or sexual orientation. Discrimination typically leads to groups being unfairly treated on the basis of perceived statuses based on ethnic, racial, gender or religious categories. It involves depriving members of one group of opportunities or privileges that are available to members of another group.

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may include the freedom of conscience, freedom of press, freedom of religion, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, the right to security and liberty, freedom of speech, the right to privacy, the right to equal treatment under the law and due process, the right to a fair trial, and the right to life. Other civil liberties include the right to own property, the right to defend oneself, and the right to bodily integrity. Within the distinctions between civil liberties and other types of liberty, distinctions exist between positive liberty/positive rights and negative liberty/negative rights.

Anti-discrimination law or non-discrimination law refers to legislation designed to prevent discrimination against particular groups of people; these groups are often referred to as protected groups or protected classes. Anti-discrimination laws vary by jurisdiction with regard to the types of discrimination that are prohibited, and also the groups that are protected by that legislation. Commonly, these types of legislation are designed to prevent discrimination in employment, housing, education, and other areas of social life, such as public accommodations. Anti-discrimination law may include protections for groups based on sex, age, race, ethnicity, nationality, disability, mental illness or ability, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity/expression, sex characteristics, religion, creed, or individual political opinions.

Economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR) are socio-economic human rights, such as the right to education, right to housing, right to an adequate standard of living, right to health, victims' rights and the right to science and culture. Economic, social and cultural rights are recognised and protected in international and regional human rights instruments. Member states have a legal obligation to respect, protect and fulfil economic, social and cultural rights and are expected to take "progressive action" towards their fulfilment.

Human rights are largely respected in Switzerland, one of Europe's oldest democracies. Switzerland is often at or near the top in international rankings of civil liberties and political rights observance. Switzerland places human rights at the core of the nation's value system, as represented in its Federal Constitution. As described in its FDFA's Foreign Policy Strategy 2016-2019, the promotion of peace, mutual respect, equality and non-discrimination are central to the country's foreign relations.

The right to education has been recognized as a human right in a number of international conventions, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights which recognizes a right to free, primary education for all, an obligation to develop secondary education accessible to all with the progressive introduction of free secondary education, as well as an obligation to develop equitable access to higher education, ideally by the progressive introduction of free higher education. In 2021, 171 states were parties to the Covenant.

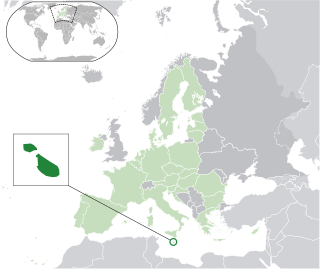

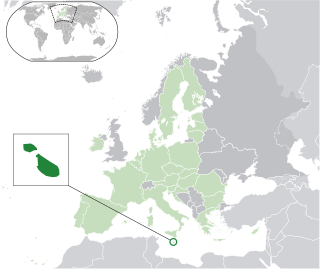

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Malta rank among the highest in the world. Throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the rights of the LGBT community received more awareness and same-sex sexual activity was legalized on 29 January 1973. The prohibition was already dormant by the 1890s.

In law, sex characteristic refers to an attribute defined for the purposes of protecting individuals from discrimination due to their sexual features. The attribute of sex characteristics was first defined in national law in Malta in 2015. The legal term has since been adopted by United Nations, European, and Asia-Pacific institutions, and in a 2017 update to the Yogyakarta Principles on the application of international human rights law in relation to sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and sex characteristics.

Human rights in Poland are enumerated in the second chapter of its Constitution, ratified in 1997. Poland is a party to several international agreements relevant to human rights, including the European Convention on Human Rights, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Helsinki Accords, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is an international human rights treaty of the United Nations intended to protect the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities. Parties to the convention are required to promote, protect, and ensure the full enjoyment of human rights by persons with disabilities and ensure that persons with disabilities enjoy full equality under the law. The Convention serves as a major catalyst in the global disability rights movement enabling a shift from viewing persons with disabilities as objects of charity, medical treatment and social protection towards viewing them as full and equal members of society, with human rights. The convention was the first U.N. human rights treaty of the twenty-first century.

Liechtenstein, a multiparty constitutional monarchy with a unicameral parliament and a government chosen by the reigning prince at its direction, is a prosperous and free country that is generally considered to have an excellent human-rights record.

Human rights in Canada have come under increasing public attention and legal protection since World War II. Prior to that time, there were few legal protections for human rights. The protections which did exist focused on specific issues, rather than taking a general approach to human rights.

Iceland is generally considered to be one of the leading countries in the world in regard to the human rights enjoyed by its citizens. Human rights are guaranteed by Sections VI and VII of Iceland's Constitution. Since 1989, a post of Ombudsman exists. Elections are free and fair, security forces report to civilian authorities, there is no state violence, and human rights groups are allowed to operate without restriction. Religious freedom is guaranteed, and discrimination based on sexual orientation is illegal.

Human rights in New Zealand are addressed in the various documents which make up the constitution of the country. Specifically, the two main laws which protect human rights are the New Zealand Human Rights Act 1993 and the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990. In addition, New Zealand has also ratified numerous international United Nations treaties. The 2009 Human Rights Report by the United States Department of State noted that the government generally respected the rights of individuals, but voiced concerns regarding the social status of the indigenous population.

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa, has a population of approximately 188,000 people. Samoa gained independence from New Zealand in 1962 and has a Westminster model of Parliamentary democracy which incorporates aspects of traditional practices. In 2016, Samoa ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities CRPD and the three optional protocols to the CRC

Tuvalu is a small island nation in the South Pacific, located North of Fiji and North West of Samoa. The population at the 2012 census was 10,837. Tuvalu has a written constitution which includes a statement of rights influenced by the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights. While most human rights in Tuvalu are respected, areas of concern include women’s rights and freedom of belief, as well as diminishing access to human rights in the face of global warming. The latter has played a major role in the implementation of human rights actions in Tuvalu given its geographical vulnerability and scarce resources.

Helena Dalli is a Maltese politician serving as European Commissioner for Equality since 1 December 2019. She is a member of the Labour Party.

The Marshall Islands is a country in the Pacific spread over 29 coral atolls, with 1,156 islands and islets. It has an estimated population of 68,480 and is one of the sixteen member states of the Pacific Islands Forum. Since 1979, the Marshall Islands has been self-governing.

Human rights in Namibia are currently recognised and protected by the Namibian constitution formed in 1990 by a 72-seat assembly. The assembly consisted of differing political parties. After a draft, the constitution was agreed upon by all members of the seven political parties involved. 21 March 1990 marks the first day Namibia operated under the Constitution and also marks the recognition of Namibia as an independent nation. Chapter 3 of the constitution entitled Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms, also referred to as the Bill of Rights, outlines the human rights of all Namibian citizens.