|

|---|

Human rights in Spain are set out in the 1978 Spanish constitution. Sections 6 and 7 guarantees the right to create and operate political parties and trade unions so long as they respect the Constitution and the law. [1]

|

|---|

Human rights in Spain are set out in the 1978 Spanish constitution. Sections 6 and 7 guarantees the right to create and operate political parties and trade unions so long as they respect the Constitution and the law. [1]

Until 2012, universal healthcare was guaranteed to all universal immigrants regardless of the administrative status. There was an attempt to change this situation under a new health law introduced in September 2012, whereby immigrants or expatriates without proper residents permits were to be refused medical care. Illegal immigrants would only be entitled to free treatment within Spain's healthcare system in cases of emergency or a pregnancy or birth. [2] This law was rejected and not applied by a majority of regions of Spain, which have ensured universal coverage to illegal immigrants. [3]

This section should include a summary of, or be summarized in, another article.(June 2018) |

This article may lack focus or may be about more than one topic.(February 2020) |

Environmental racism has been documented in Spain, with North African and Romani ethnic communities being particularly affected, as well as migrant agricultural workers from throughout Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Southeast Europe. As of 2007, there were an estimated 750,000 Romani (primarily Gitano Romani) living in Spain. [4] : 3 According to the "Housing Map of the Roma Community in Spain, 2007", 12% of Romani live in substandard housing, while 4%, or 30,000 people, live in slums or shantytowns; furthermore, 12% resided in segregated settlements. [4] : 8 According to the Roma Inclusion Index 2015, the denial of environmental benefits has been documented in some communities, with 4% of Romani in Spain not having access to running water, and 9% not having access to electricity. [4] : 8

Efforts to relocate shantytowns (chabolas), which according to a 2009 report by the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights were disproportionately inhabited by Romani persons, [5] : 4 gained momentum in the late 1980s and 1990s. [6] : 315 These initiatives were ostensibly designed to improve Romani living conditions, yet also had the purpose of being employed to vacate plots of real estate for development. [6] : 315 In the words of a 2002 report on the situation of Romani in Spain, "thousands of Roma live in transitional housing, without any indication of when the transition period will end," a situation which has been attributed to the degradation of many transitional housing projects into ghettoes. [6] : 316 In the case of many such relocations, Romani people have been moved to the peripheries of urban centers, [6] : 315, 317 often in environmentally problematic areas. [6] : 316 In the case of Cañada Real Galiana, diverse ethnic groups including non-Romani Spaniards and Moroccans have been documented as experiencing issues of environmental injustice alongside Romani communities. [7] : 16 [8] : 13–15

In 2002, 16 Romani families in El Cascayu were relocated under a transitional housing scheme to what has been described by the organization SOS Racismo as a discriminatory, isolated, and environmentally marginalized housing location. [6] : 317 According to SOS Racismo,

... the last housing units built within [the] eradication of marginalization plan in El Cascayu, where 16 families will be re-housed, is a way of chasing these families out of the city. They will live in a place surrounded by a 'sewer river,' a railroad trail, an industrial park and a highway. So far away from education centres, shops, recreational places and without public transport, it will be physically difficult for them to get out of there. [6] : 317

On the outskirts of Madrid, 8,600 persons inhabit the informal settlement of Cañada Real Galiana, [7] : 16 also known as La Cañada Real Riojana or La Cañada Real de las merinas. [8] : 10 It constitutes the largest shantytown in Western Europe. [7] : 1 The settlement is located along 16 kilometres of a 75-metre-wide, 400 kilometre-long environmentally protected transhumance trail between Getafe and Coslada, [7] : 2–3 [8] : 10 part of a 125,000 kilometre network of transhumance routes throughout Spain. [8] : 10 Certain areas of the unplanned and unauthorized settlement are economically affluent, working-class, or middle-class [7] : 3 [8] : 12 and are viewed as desirable areas for many (particularly Moroccan immigrants who have faced discrimination in the broader Spanish rental market). [7] : 9 [8] : 12 However, much of the Cañada Real Galiana is subject to severe environmental racism, [7] : 8 particularly in the Valdemingómez district of the settlement. [8] : 13–16

Throughout southern Spain, migrant workers from Africa, Asia, Latin America, and South East Europe employed in the agricultural sector have experienced housing and labour conditions that could be defined as environmental racism, producing food for larger European society while facing extreme deprivations. [9] [10] [11]

In Murcia, lettuce pickers have complained of having to illegally work for salary by volume for employment agencies, instead of by the hour, meaning they are required to work more hours for less pay, while also experiencing unsafe exposure to pesticides. [10] Workers have alleged that they have been forced to work in fields while pesticide spraying is active, a practice which is illegal under Spanish work safety laws. [9] [10]

Beginning in the 2000s in the El Ejido region of Andalusia, African (including large numbers of Moroccan) immigrant greenhouse workers have been documented as being faced with severe social marginalization and racism while simultaneously being exposed to extremely difficult working conditions with significant exposure to toxic pesticides. [10] [11] The El Ejido region has been described by environmentalists as a "sea of plastic" due to the expansive swaths of land covered by greenhouses, and has also been labeled "Europe's dirty little secret" due to the documented abuses of workers who help produce large quantities of Europe's food supply. [11]

In these greenhouses, workers are allegedly required to work under "slave-like" conditions in temperatures as high as 50 degrees Celsius with nonexistent ventilation, while being denied basic rest facilities and earning extremely low wages, among other workplace abuses. [9] [10] As of 2015, out of 120,000 immigrant workers employed in the greenhouses, 80,000 are undocumented and not protected by Spanish labour legislation, according to Spitou Mendy of the Spanish Field Workers Syndicate (SOC). [9] Workers have complained of ill health effects as a result of exposure to pesticides without proper protective equipment. [9] [10]

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another articletitled Racism in Spain . (Discuss) (February 2020) |

Following the killing of two Spanish farmers and a Spanish woman in two separate incidents involving Moroccan citizens in February 2000, an outbreak of xenophobic violence took place in and around El Ejido, injuring 40 and displacing large numbers of immigrants. [12] [13] According to Angel Lluch

For three days on end, from 5 to 7 February, racist violence swept the town with immigrants as its target. For 72 hours hordes of farmers wielding iron bars, joined by youths from the high schools, beat up their victims, chased them through the streets and pursued them out among the greenhouses. Roads were blocked, barricaded and set aflame. [13]

In the strawberry industry in the province of Huelva, around 2018–2019, some incidents of rape, forced prostitution of migrant workers and poor housing conditions and sanitation have been claimed. [14]

This article may lack focus or may be about more than one topic.(February 2020) |

In February 2014, a Spanish court ordered the arrest of China's former Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin and former Premier Li Peng for the alleged genocide and torture of the people of Tibet. [15] The Chinese government expressed anger at the actions of the Spanish court, with foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying stating "China is strongly dissatisfied and firmly opposed to the erroneous acts taken by the Spanish agencies in disregard of China's position." [16] In May 2014, in response to the diplomatic situation, the Spanish government repealed the universal jurisdiction law. [17]

Former judge Baltasar Garzón has criticized the government's reform. Commenting on the judges ability to prosecute foreign crimes against humanity, genocides, and war crimes; he said, "The conditions that they're imposing are so exorbitant that it would be almost impossible to prosecute these crimes. [18]

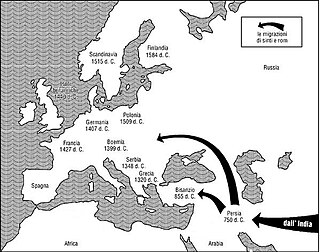

The Romani people, also known as the Roma, are an ethnic group of Indo-Aryan origin who traditionally lived a nomadic, itinerant lifestyle. Linguistic and genetic evidence suggests that the Roma originated in the Indian subcontinent, in particular the region of Rajasthan. Their first wave of westward migration is believed to have occurred sometime between the 5th and 11th centuries. They are thought to have arrived in Europe around the 13th to 14th century. Although they are widely dispersed, their most concentrated populations are believed to be in Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, Serbia and Slovakia.

In 2008 there were about 500-700 Romani people in Mitrovica refugee camps. These three camps were created by the UN in Kosovo. The camps are based around disused heavy metals mines which have fallen out of use since the end of the Kosovo War of 1999. There have been complaints that the residents are suffering severe lead poisoning. According to a 2010 Human Rights Watch, Romani displaced from the Romani quarter in Mitrovica, due to its destruction in 2000, continued to be inmates of camps in north Mitrovica, where they were exposed to environmental lead poisoning.

The Romani in Spain, generally known by the endonym Calé, or the exonym gitanos, belong to the Iberian Romani subgroup known as Calé, with smaller populations in Portugal and in Southern France. Their sense of identity and cohesion stems from their shared value system, expressed among gitanos as las leyes gitanas.

El Ejido is a municipality of Almería province, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. It is located 32 km from Almería with a surface area of 227 km2, and as reported in 2014 had 84,144 inhabitants. El Ejido is the centre of production for fruit and vegetables in the "Comarca de El Poniente". The work opportunities the city provides attract many foreign farmhands, who look for jobs mainly in the greenhouses there. Some greenhouses have begun using computer-controlled hydroponics systems, thus saving on labour, improving efficiency and the local economy.

Anti-Romani sentiment is an ideology which consists of hostility, prejudice, discrimination, racism and xenophobia which is specifically directed at Romani people. Non-Romani itinerant groups in Europe such as the Yenish, Irish and Highland Travellers are frequently given the name "gypsy" and as a result, they are frequently confused with the Romani people. As a result, sentiments which were originally directed at the Romani people are also directed at other traveler groups and they are frequently referred to as "antigypsy" sentiments.

A farmworker, farmhand or agricultural worker is someone employed for labor in agriculture. In labor law, the term "farmworker" is sometimes used more narrowly, applying only to a hired worker involved in agricultural production, including harvesting, but not to a worker in other on-farm jobs, such as picking fruit.

The Romani diaspora refers to the presence and dispersion of Romani people across various parts of the world. Their migration out of the Indian subcontinent occurred in waves, with the first estimated to have taken place between the 1st and 2nd century AD. They are believed to have first arrived in Europe in the early 12th century, via the Balkans. They settled in the areas of present-day Turkey, Greece, Serbia, Romania, Croatia, Moldova, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Hungary, Albania, Kosovo, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Czech Republic, Slovenia and Slovakia, by order of volume, and Spain. From the Balkans, they migrated throughout Europe and, in the 19th and later centuries, to the Americas. The Roma population in the United States is estimated at more than one million.

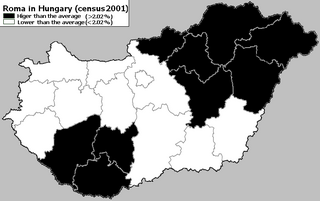

Romani people in Hungary are Hungarian citizens of Romani descent. According to the 2011 census, they comprise 3.18% of the total population, which alone makes them the largest minority in the country, although various estimations have put the number of Romani people as high as 8.8% of the total population. They are sometimes referred as Hungarian Gypsies, but that is sometimes considered to be a racial slur.

The Romani people of Greece, or Romá, are called Tsinganoi, Athinganoi (Αθίγγανοι), or the more derogatory term Gyftoi. On 8 April 2019, the Greek government stated that the number of Greek Roma citizens in Greece is around 110,000. Other estimates have placed the number of Romani people resident in Greece as high as 350,000.

Racism has been a recurring part of the history of Europe.

Racism in Italy refers to the existence of antagonistic relationships between Italians and other populations of different ethnicities which has existed throughout the country's history.

Racism in Spain can be traced back to any historical era, during which social, economic and political conflicts have efficiently been justified by racial differences, be it in the form of racism as an ideology or in the form of racism as simple attitudes or behaviors towards those who are perceived as being different. More common than racism per se are the attitudes linked to xenophobia and nationalism, as well as religious and/or linguistic-cultural hatred.

El Ejido, la loi du profit is a Belgian 2006 documentary film.

Cañada Real is a shanty town in the Madrid Region of Spain, a linear succession of informal housing following a 14.4-kilometre-long stretch of the drovers' road connecting La Rioja and Ciudad Real. The largest illegal settlement in a European city, it extends through the municipalities of Coslada, Rivas-Vaciamadrid and Madrid.

The Romani people in Poland are an ethnic minority group of Indo-Aryan origins in Poland. The Council of Europe regards the endonym "Roma" as more appropriate when referencing the people, and "Romani" when referencing cultural characteristics. The term Cyganie is considered an exonym in Poland.

Environmental injustice is the exposure of poor and marginalised communities to a disproportionate share of environmental harms such as hazardous waste, when they do not receive benefits from the land uses that create these hazards. Environmental racism is environmental injustice in a racialised context. These issues may lead to infringement of environmentally related human rights. Environmental justice is a social movement to address these issues.

The intensive agriculture of the province of Almeria, Spain, is a model of the utilization of highly technical means to achieve maximum economic yield based on the rational use of water, use of plastic greenhouses, highly technical training and high levels of employment of inputs, applied to the special characteristics of a particular environment. The greenhouses (invernaderos) are located between Motril and Almeria. The area of El Ejido is well known to be agriculturally productive.

From 5 to 7 February 2000, the Spanish town of El Ejido in the province of Almería experienced race riots against its Moroccan agricultural workers. The rioting was triggered by the recent murders of two Spanish men and a Spanish woman by two separate Moroccan individuals. The rioting was described at the time as the worst instances of racial violence in modern Spanish history.

Environmental racism is a form of institutional racism leading to landfills, incinerators, and hazardous waste disposal being disproportionally placed in communities of colour. This includes the lack of minority and indigenous representation in environmental decision-making and inequality in resource development. Internationally, it is also associated with extractivism, which places the environmental burdens of mining, oil extraction, and industrial agriculture upon Indigenous peoples and poorer nations largely inhabited by people of colour.

Environmental racism in Central and Eastern Europe is well documented. In Central and Eastern Europe, socialist governments have generally prioritized industrial development over environmental protection, in spite of growing public and governmental environmental awareness in the 1960s and 1970s. Even though public concern over the environmental effects of industrial expansion such as mine and dam construction grew in the late 1980s and early 1990s, policy makers continued to focus on privatization and economic development. Following the market transition, environmental issues have persisted, despite some improvements during the early stages of transition. Throughout this time, significant social restructuring took place alongside environmental changes.