| Viện nghiên cứu Hán Nôm 院研究漢喃 | |

| Formation | 1970 (foundation) 1979 (institute status) |

|---|---|

| Type | GO |

| Legal status | Active |

| Purpose | Language researching |

| Headquarters | Hanoi, Vietnam |

| Location |

|

| Coordinates | 21°00′52″N105°49′19″E / 21.014327352670257°N 105.82208121871022°E |

Official language | Vietnamese |

Director | Dr. Nguyễn Tuấn Cường (阮俊強) |

Staff | 66 |

| Website | www |

Formerly called | the Department of Hán and Nôm |

- 5 offices on scientific researching

- the Office of Philology

- the Office of Regional and Ethnic Documents

- the Office of Colophon

- the Office of Ancient Books

- the Office of Study and Application of Hán-Nôm

- 6 offices on scientific services

- the Office of Data Preservation

- the Office of Data Searching

- the Office of Information Application

- the Office of Library and Communicating Information

- the Office of Duplication

- the Office of Integrated Administration

In addition, the institute publishes four editions of Hán-Nôm Studies magazine every year to provide scholastic trends and research findings of Hán-Nôm.

Cultural exchanges

In 2005, a delegation led by Prof. Zhang Liwen (張立文) and Peng Yongjie (彭永捷) from the Confucius Institute of the Renmin University of China arrived at the Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies, both sides signed the Agreement on Cooperatively Compiling the Confucian Canon of Vietnam. In 2006, Doctor Phan of the Hán-Nôm Institute paid a return visit and discussed the book's compilation with the Renmin University of China. Like the Confucian Canon of Korea (韓國儒典), the Confucian Canon of Vietnam (越南儒典) is a part of the International Confucian Canon (國際儒典) – an important, East Asian Studies-oriented project of the Confucius Institute at the Renmin University of China. [9]

In 2010, three years after the joint compilation of the Hán-Nôm Institute and the Fudan University, Shanghai, the Collection of Vietnamese's Long Journey to the Yan in Classical Chinese (越南漢文燕行文獻集成, in which Yan means Yanjing, an ancient city located in modern Beijing) was published by Fudan University Press. On June 13, the two organizations held a new book launch, which was attended by Trịnh Khắc Mạnh, Ge Zhaoguang (葛兆光, the dean of the National Institute for Advanced Humanistic Studies of Fudan University), other leaders of the university and local officials. [10]

The Collection of Vietnamese's Long Journey to the Yan in Classical Chinese included the records of Vietnamese envoys' trip to China during the period of the Trần, Later Lê, Tây Sơn and Nguyễn dynasties of Vietnam. In their journeys, the envoys traveled from place to place, chanting poetry, painting pictures and even communicating with other envoys from Joseon and the Ryukyu Kingdom. These are regarded as proofs of early cultural exchanges between countries in East Asia and bases of the development of the Sinic world. [10]

Library

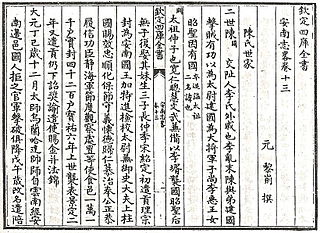

The Hán-Nôm Institute stores manuscripts dating from approximately 14th century to 1945. There are 20,000 ancient books among all the collections, most of them are in Nôm script (including the Nôm of Kinh, Nùng and Yao) and traditional Chinese characters. Besides, the institute also has 15,000 woodblocks and 40,000 rubbings from stele, bronze bells, chime stones and wooden plates, the history of which can be traced back to 10th to 20th century. [4] [11]

About 50% of the institute's collections are Vietnamese works of literature. The rest includes volumes related to geography, Buddhism and epigraphy, etc. The catalogue is available both in Chinese and French, so researchers who cannot understand Vietnamese are able to use and study the resources with no difficulty. [11]

Unfortunately, the library has only Vietnamese forms and, apart from a few senior personnel, many librarians speak neither Chinese nor English.

Before accessing the library, visitors are suggested to e-mail a senior librarian. One should submit two passport photos on arrival and pay 30,000 dong to maintain a 6-month readership. A graduate student will have to provide a letter of recommendation from one's supervisor. [11]

The opening hours of the library is 8:30 am – 11:45 am, 2:00 pm – 4:15 pm through Mondays to Thursdays and 8:30 am – 11:45 am on Fridays. The request of books has a maximum of ten per day and asking for permission is required if one wants to take away the photography of manuscripts, except those with maps which are not allowed to be photographed. Photocopying service, which also needs permission, is priced at 2000 Dong per page. [11]

Scriptures stored

In 2008, Takeuchi Fusaji (武内 房司), a professor of Chinese History at the Department of Literature of Gakushuin University, Japan, published a research paper entitled Transmission of the Chinese Sectarian Religion and its Vietnam Adaptation: an Introduction of the Scriptures of the Institute of Han-Nom Studies of Vietnam. It introduced some ancient, Chinese religious culture-related books collected by the Hán-Nôm Institute. The paper itself was translated into Chinese by the Qing History Journal of Renmin University of China in 2010.

The books mentioned by Takeuchi's paper include: [12]

- The Scripture of Eradicating Puzzles (破迷宗旨): resisting the lure of wealth and status, an old man called Rutong (儒童) engaged in benefactions and eventually became a nobleman in 'the Abode of Immortals' of supernatural beings.

- The Queen Mother's Repentance of Removing Ill Fortunes and Saving the World (瑤池王母消劫救世寶懺): the record of oracles during the Gods Worshipping Ceremony at Kaihua Fu, Yunnan of China in June 1860 was made into scriptures and was collected by the famous Ngọc Sơn Temple at Hanoi. The Temple was allegedly constructed in Lê dynasty.

- The Holy Scripture of Maitreya's Succouring the World (彌勒度世尊經) and the Narration of Maitreya's Real Scriptures (彌勒真經演音): Siddhārtha Gautama gained the chance to rule the world but caused disasters due to his incompetence, then Maitreya salvaged all living creatures. (Such stories are different from orthodox sutras)

See also

- The Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation, a similar organization in Cary, North Carolina, the United States.

Related Research Articles

The Nguyễn dynasty was the last Vietnamese dynasty, which was preceded by the Nguyễn lords and ruled the unified Vietnamese state independently from 1802 to 1883 before being a French protectorate. During its existence, the empire expanded into modern-day southern Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos through a continuation of the centuries-long Nam tiến and Siamese–Vietnamese wars. With the French conquest of Vietnam, the Nguyễn dynasty was forced to give up sovereignty over parts of southern Vietnam to France in 1862 and 1874, and after 1883 the Nguyễn dynasty only nominally ruled the French protectorates of Annam as well as Tonkin. They later cancelled treaties with France and were the Empire of Vietnam for a short time until 25 August 1945.

Spoken and written Vietnamese today uses the Latin script-based Vietnamese alphabet to represent native Vietnamese words, Vietnamese words which are of Chinese origin, and other foreign loanwords. Historically, Vietnamese literature was written by scholars using a combination of Chinese characters (Hán) and original Vietnamese characters (Nôm). From 111 BC up to the 20th century, Vietnamese literature was written in Văn ngôn using chữ Hán, and then also Nôm from the 13th century to 20th century.

Ma Yuan, courtesy name Wenyuan, also known by his official title Fubo Jiangjun, was a Chinese military general and politician of the Eastern Han dynasty. He played a prominent role in defeating the Trung sisters' rebellion.

Vietnamese literature is the literature, both oral and written, created largely by the Vietnamese. Early Vietnamese literature has been greatly influenced by Chinese literature. As Literary Chinese was the formal written language for government documents, a majority of literary works were composed in Hán văn or as văn ngôn. From the 10th century, a minority of literary works were composed in chữ Nôm, the former writing system for the Vietnamese language. The Nôm script better represented Vietnamese literature as it led to the creation of different poetic forms like Lục bát and Song thất lục bát. It also allowed for Vietnamese reduplication to be used in Vietnamese poetry.

Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary is a layer of about 3,000 monosyllabic morphemes of the Vietnamese language borrowed from Literary Chinese with consistent pronunciations based on Middle Chinese. Compounds using these morphemes are used extensively in cultural and technical vocabulary. Together with Sino-Korean and Sino-Japanese vocabularies, Sino-Vietnamese has been used in the reconstruction of the sound categories of Middle Chinese. Samuel Martin grouped the three together as "Sino-xenic". There is also an Old Sino-Vietnamese layer consisting of a few hundred words borrowed individually from Chinese in earlier periods. These words are treated by speakers as native words. More recent loans from southern Chinese languages, usually names of foodstuffs such as lạp xưởng 'Chinese sausage', are not treated as Sino-Vietnamese but more direct borrowings.

Vietnamese era names were titles adopted in historical Vietnam for the purpose of year identification and numbering.

Ngô Sĩ Liên (吳士連) was a Vietnamese historian of the Lê dynasty. He was the main compiler of the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, a chronicle of the history of Vietnam and a historical record of a Vietnamese dynasty. Ngô based information for his historical book from collections of myths and legends such as Trần Thế Pháp's Lĩnh Nam chích quái or Việt điện u linh tập.

Bình Ngô đại cáo was an announcement written by Nguyễn Trãi in 1428, at Lê Lợi's behest and on Lê Lợi's behalf, to proclaim the Lam Sơn's victory over the Ming imperialists and affirm the independence of Đại Việt to its people.

The Đại Việt sử lược or Việt sử lược is an historical text that was compiled during the Trần dynasty. The three-book work was finished around 1377 and covers the history of Vietnam from the reign of Triệu Đà to the collapse of the Lý dynasty. During the Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam, the book, together with almost all official records of the Trần dynasty, was taken away to China and subsequently collected in the Siku Quanshu. The Đại Việt sử lược is considered the earliest chronicle about the history of Vietnam that remains today.

The An Nam chí lược is a historical text that was compiled by the Vietnamese historian Lê Tắc during his exile in Yuan China in early 14th century. Published for the first time in 1335 in the Yuan dynasty, An Nam chí lược became one of the few historical books about Đại Việt that survive from the 14th and 15th centuries, and it is considered the oldest historical work by a Vietnamese that has been preserved.

Đường luật is the Vietnamese variant of Chinese Tang poetry. Đường also means Tang dynasty, but in Vietnam the original Chinese Tang poems are distinguished from Vietnam's own native thơ Đường luật as China's "Thơ Đường" or "Đường thi".

The Confucian court examination system in Vietnam was a system for entry into the civil service, which was modelled after the Imperial examination in China, based on knowledge of the classics and literary style from 1075 to 1919.

Chữ Nôm is a logographic writing system formerly used to write the Vietnamese language. It uses Chinese characters to represent Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary and some native Vietnamese words, with other words represented by new characters created using a variety of methods, including phono-semantic compounds. This composite script was therefore highly complex and was accessible to less than five percent of the Vietnamese population who had mastered written Chinese.

Literary Chinese was the medium of all formal writing in Vietnam for almost all of the country's history until the early 20th century, when it was replaced by vernacular writing in Vietnamese using the Latin-based Vietnamese alphabet. The language was the same as that used in China, as well as in Korea and Japan, and used the same standard Chinese characters. It was used for official business, historical annals, fiction, verse, scholarship, and even for declarations of Vietnamese determination to resist Chinese invaders.

Vietnamese calligraphy relates to the calligraphic traditions of Vietnam. It includes calligraphic works using a variety of scripts, including historical chữ Hán, chữ Nôm, and the Latin-based Vietnamese alphabet. Historically, calligraphers used the former two scripts. However, due to the adoption of the Latin-based chữ Vietnamese alphabet, modern Vietnamese calligraphy also uses Latin script alongside chữ Hán Nôm.

The Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation, shortened as the Nôm Foundation and abbreviated as VNPF, was an American nonprofit agency for language preservation headquartered in Cary, North Carolina, with an office in Hanoi, Vietnam. Established in 1999, it was engaged in the preservation of Chữ Nôm script remained in manuscripts, inscriptions and woodblocks. In 2018, the Foundation declared its initial goal achieved and dissolved itself.

Chữ Hán are the Chinese characters that were used to write Literary Chinese and Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary in Vietnam. They were officially used in Vietnam after the Red River Delta region was incorporated into the Han dynasty and continued to be used until the early 20th century where usage of Literary Chinese was abolished alongside the Confucian court examinations causing chữ Hán to be no longer used in favour of the Vietnamese alphabet.

During the Nguyễn dynasty period (1802–1945) of Vietnamese history its Ministry of Education was reformed a number of times, in its first iteration it was called the Học Bộ which was established during the reign of the Duy Tân Emperor (1907–1916) and took over a number of functions of the Lễ Bộ, one of the Lục Bộ. The Governor-General of French Indochina wished to introduce more education reforms, the Nguyễn court in Huế sent Cao Xuân Dục and Huỳnh Côn, the Thượng thư of the Hộ Bộ, to French Cochinchina to discuss these reforms with the French authorities. After their return the Học Bộ was established in the year Duy Tân 1 (1907) with Cao Xuân Dục being appointed to be its first Thượng thư (minister). Despite nominally being a Nguyễn dynasty institution, actual control over the ministry fell in the hands of the French Council for the Improvement of Indigenous Education in Annam.

The Mechanics and Crafts of the People of Annam is a multi-volume colonial manuscript created by Henri Joseph Oger (1885-1936), a colonial official who commissioned artists to record the culture of the Annamese (Vietnamese) in Hanoi and the area around it during the French colonial administration of Tonkin. The manuscript was published by Henri Joseph Oger in 1908 – 1909.

Đào Thái Hanh, courtesy name Gia Hội (嘉會), art name Sa Giang (沙江) and Mộng Châu (夢珠), was a Vietnamese mandarin of the Nguyễn dynasty. As one of the earliest collaborators of Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Hué since its establishment in 1914, his articles for the magazine have left many valuable studies on the history and culture of Huế.

References

- ↑ Nhung Tuyet Tran, Anthony Reid Việt Nam: Borderless Histories 2006 – Page 141 "The version of the Lê Code used in this essay can be found at the Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies."

- ↑ Nong Van Dan, Churchill, Eden and Indo-China, 1951–1955 2011 Page xix "the Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies"

- ↑ National Center for Social Sciences and Humanities of Vietnam (NCSSH).2000 – Page 32 "The former organization of the Institute of Han-Nom Studies was the department of Han-Nom, established in 1970. In 1979, the department became the Institute of Han-Nom Studies and this was reconfirmed on May 22, 1993."

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 漢喃研究院 [the Institute of Han-Nom Studies] (in Chinese). National Chung Cheng University, Taiwan. n.d. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ↑ Thư mục thác bản văn khắc Hán Nôm Việt Nam Khá̆c Mạnh Trịnh, Lan Anh Vũ, Viện nghiên cứu Hán Nôm (Vietnam) – 2007- Volume 1 – Page 28 "For this reason, in 1970–1975, the Hán-Nôm Committee, an agency of the Vietnamese Committee of Social Sciences, got down to ... After the collection was transferred from the Central Library to the Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies, in 1984–1986, this institute ... Finally, in 1988–1990, the Specialists of the Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies launched the first programme for the treatment of the rubbings, which resulted in the production of the Catalogue of Rubbings of Vietnamese Inscription (Danh mục thác"

- ↑ Asian research trends: a humanities and social science review – No 8 to 10 – Page 140 Yunesuko Higashi Ajia Bunka Kenkyū Sentā (Tokyo, Japan) – 1998 "Most of the source materials from premodern Vietnam are written in Chinese, obviously using Chinese characters; however, a portion of the literary genre is written in Vietnamese, using chu nom. Therefore, han nom is the term designating the whole body of premodern written materials.."

- ↑ Liam C. Kelley Beyond the bronze pillars: envoy poetry and the Sino-Vietnamese ... - 2005 Page 215 "For more on these texts, see Tran Van Giap, Tim hieu kho sack Han Norn, Tap I [Investigating the treasury of books in Han and Nom] (Hanoi: Thu vien Quoc gia, 1970), 196-198, and Tran Van Giap, Tim hieu kho sack Han Nom, Tap II, 229-230, "

- ↑ Viet Nam social sciences Ủy ban khoa học xã hội Việt Nam – 2008 – No 1-3 – Page 2 "As you may know, the Institute of Han-Nom Studies performs multiple functions of preserving, researching and bringing into full play the values of Han-Nom heritage."

- ↑ Zhu Lu (朱璐) (5 March 2006). 越南汉喃研究院范文深博士访问我院 [Doctor Phan from the Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies of Vietnam visited our Institute] (in Chinese). Confucius Online, the Renmin University of China. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- 1 2 中越合作《越南汉文燕行文献集成》出版 [The Collection of Vietnamese's Long Journey to the Yan in Traditional Chinese Published under Sino-Vietnamese Cooperation] (in Chinese). the National Institute for Advanced Humanistic Studies, Fudan University. 17 June 2010. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Mok Mei Feng (8 August 2008). "Researching History: Libraries in Hanoi, Vietnam". Citizen Historian. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ↑ Takeuchi Fusaji (武内 房司) (February 2010). 中国民众宗教的传播及其在越南的本土化——汉喃研究院所藏诸经卷简介 [Transmission of the Chinese Sectarian Religion and its Vietnam Adaptation: an Introduction of the Scriptures of the Institute of Han-Nom Studies of Vietnam] (in Chinese). the Qing History Journal, Renmin University of China. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

External links

- Official website Archived 2013-02-23 at the Wayback Machine (in Vietnamese)

- NGỤC TRUNG NHẬT KÝ (Hồ Chủ Tịch) Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine Diaries written in Prison (Chairman Ho) – Ho Chi Minh's diaries on the institute's website (in Chinese)

| Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies | |

|---|---|

| Vietnamese name | |

| Vietnamese | Viện nghiên cứu Hán Nôm |

| Hán-Nôm | 院 研 究 漢 喃 |

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |