The Iranian Green Movement or Green Wave of Iran, also referred to as the Persian Awakening or Persian Spring by the western media, refers to a political movement that arose after the June 12, 2009 Iranian presidential election and lasted until early 2010, in which protesters demanded the removal of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad from office. Green was initially used as the symbol of Mir Hossein Mousavi's campaign, but after the election it became the symbol of unity and hope for those asking for annulment of what they regarded as a fraudulent election. Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi are recognized as political leaders of the Green Movement. Grand Ayatollah Hossein-Ali Montazeri was also mentioned as spiritual leader of the movement.

Internet activism, hacktivism, or hactivism, is the use of computer-based techniques such as hacking as a form of civil disobedience to promote a political agenda or social change. With roots in hacker culture and hacker ethics, its ends are often related to free speech, human rights, or freedom of information movements.

An Internet bot, web robot, robot or simply bot, is a software application that runs automated tasks (scripts) on the Internet, usually with the intent to imitate human activity, such as messaging, on a large scale. An Internet bot plays the client role in a client–server model whereas the server role is usually played by web servers. Internet bots are able to perform simple and repetitive tasks much faster than a person could ever do. The most extensive use of bots is for web crawling, in which an automated script fetches, analyzes and files information from web servers. More than half of all web traffic is generated by bots.

Controversies of the former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad included criticism after his election victory on June 29, 2005. These include charges that he participated in the 1979-1981 Iran Hostage Crisis, assassinations of Kurdish politicians in Austria, torture, interrogation and executions of political prisoners in the Evin prison in Tehran. Ahmadinejad and his political supporters have denied these allegations.

In Iran, censorship was ranked among the world's most extreme in 2024. Reporters Without Borders ranked Iran 176 out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index, which ranks countries from 1 to 180 based on the level of freedom of the press. Reporters Without Borders described Iran as “one of the world’s five biggest prisons for media personnel" in the 40 years since the revolution. In the Freedom House Index, Iran scored low on political rights and civil liberties and has been classified as 'not free.'

The Internet has a long history of turbulent relations, major maliciously designed disruptions, and other conflicts. This is a list of known and documented Internet, Usenet, virtual community and World Wide Web related conflicts, and of conflicts that touch on both offline and online worlds with possibly wider reaching implications.

Microblogging is a form of blogging using short posts without titles known as microposts. Microblogs "allow users to exchange small elements of content such as short sentences, individual images, or video links", which may be the major reason for their popularity. Some popular social networks such as X (Twitter), Threads, Tumblr, Mastodon and Instagram can be viewed as collections of microblogs.

Anonymous is a decentralized international activist and hacktivist collective and movement primarily known for its various cyberattacks against several governments, government institutions and government agencies, corporations and the Church of Scientology.

After incumbent president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad declared victory in the 2009 Iranian presidential election, protests broke out in major cities across Iran in support of opposition candidates Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi. The protests continued until 2010, and were titled the Iranian Green Movement by their proponents, reflecting Mousavi's campaign theme, and Persian Awakening, Persian Spring or Green Revolution.

Twitter Revolution is a term used to refer to different revolutions and protests, most of which featured the use of the social networking site X, formerly and colloquially known as Twitter, by protesters and demonstrators in order to communicate.

Following the 2009 Iranian presidential election, protests against alleged electoral fraud and in support of opposition candidates Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi occurred in Tehran and other major cities in Iran and around the world starting after the disputed presidential election on 2009 June 12 and continued even after the inauguration of Mahmoud Ahmedinejad as President of Iran on 5 August 2009. This is a timeline of the events which occurred during those protests.

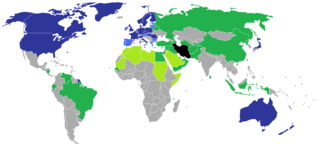

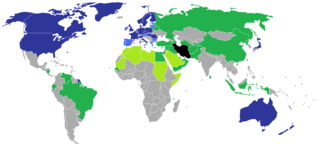

Reactions to the 2009 Iranian presidential election varied across the world. Most Western countries expressed concern, while most countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa that expressed any opinion congratulated Mahmoud Ahmadinejad for his victory. The UN and EU also expressed concern about the aftermath.

Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei is an Iranian conservative politician and former intelligence officer. As a senior Cabinet member in the administration of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, he served as Chief of Staff from 2009 to 2013, and served as the fourth first vice president of Iran for one week in 2009 until his resignation was ordered by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Haystack was a never-completed program intended for network traffic obfuscation and encryption. It was promoted as a tool to circumvent internet censorship in Iran. Shortly after the release of the first test version, reviewers concluded the software did not live up to promises made about its functionality and security, and would leave its users' computers more vulnerable.

Operation Payback was a coordinated, decentralized group of attacks on high-profile opponents of Internet piracy by Internet activists using the "Anonymous" moniker. Operation Payback started as retaliation to distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks on torrent sites; piracy proponents then decided to launch DDoS attacks on piracy opponents. The initial reaction snowballed into a wave of attacks on major pro-copyright and anti-piracy organizations, law firms, and individuals. The Motion Picture Association of America, the Pirate Party UK and United States Pirate Party criticised the attacks.

Censorship of Twitter refers to Internet censorship by governments that block access to Twitter. Twitter censorship also includes governmental notice and take down requests to Twitter, which it enforces in accordance with its Terms of Service when a government or authority submits a valid removal request to Twitter indicating that specific content published on the platform is illegal in their jurisdiction.

Anonymous is a decentralised virtual community. They are commonly referred to as an internet-based collective of hacktivists whose goals, like its organization, are decentralized. Anonymous seeks mass awareness and revolution against what the organization perceives as corrupt entities, while attempting to maintain anonymity. Anonymous has had a hacktivist impact. This is a timeline of activities reported to be carried out by the group.

Hotspot Shield is a public VPN service operated by AnchorFree, Inc. Hotspot Shield was used to bypass government censorship during the Arab Spring protests in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya.

High Orbit Ion Cannon (HOIC) is an open-source network stress testing and denial-of-service attack application designed to attack as many as 256 URLs at the same time. It was designed to replace the Low Orbit Ion Cannon which was developed by Praetox Technologies and later released into the public domain. The security advisory for HOIC was released by Prolexic Technologies in February 2012.

BlueLeaks, sometimes referred to by the Twitter hashtag #BlueLeaks, refers to 269.21 gibibytes of internal U.S. law enforcement data obtained by the hacker collective Anonymous and released on June 19, 2020, by the activist group Distributed Denial of Secrets, which called it the "largest published hack of American law enforcement agencies".