Richard Allen was a minister, educator, writer, and one of the United States' most active and influential black leaders. In 1794, he founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), the first independent Black denomination in the United States. He opened his first AME church in 1794 in Philadelphia.

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a Methodist denomination based in the United States. It adheres to Wesleyan–Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. It cooperates with other Methodist bodies through the World Methodist Council and Wesleyan Holiness Connection.

Henry Highland Garnet was an American abolitionist, minister, educator, orator, and diplomat. Having escaped as a child from slavery in Maryland with his family, he grew up in New York City. He was educated at the African Free School and other institutions, and became an advocate of militant abolitionism. He became a minister and based his drive for abolitionism in religion.

Absalom Jones was an African-American abolitionist and clergyman who became prominent in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Disappointed at the racial discrimination he experienced in a local Methodist church, he founded the Free African Society with Richard Allen in 1787, a mutual aid society for African Americans in the city. The Free African Society included many people newly freed from slavery after the American Revolutionary War.

Benjamin William Arnett was an American educator, minister, bishop and member of the Ohio House of Representatives.

The black church is the faith and body of Christian denominations and congregations in the United States that predominantly minister to, and are also led by African Americans, as well as these churches' collective traditions and members. The term "black church" may also refer to individual congregations, including in traditionally white-led denominations.

William J. Simmons was an American Baptist pastor, educator, author, and activist. He was a former enslaved person who became the second president of Simmons College of Kentucky (1880–1890), for whom the school was later named.

Jehu Jones Jr. (1786–1852) was a Lutheran minister who founded one of the first African-American Lutheran congregations in the United States, as well as actively involved in improving the social welfare of blacks.

Daniel Coker (1780–1846), born Isaac Wright, was an African American of mixed race from Baltimore, Maryland. Born a slave, after he gained his freedom, he became a Methodist minister in 1802. He wrote one of the few pamphlets published in the South that protested against slavery and supported abolition. In 1816, he helped found the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent black denomination in the United States, at its first national convention in Philadelphia.

Henry McNeal Turner was an American minister, politician, and the 12th elected and consecrated bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). After the American Civil War, he worked to establish new A.M.E. congregations among African Americans in Georgia. Born free in South Carolina, Turner learned to read and write and became a Methodist preacher. He joined the AME Church in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1858, where he became a minister. Founded by free blacks in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the early 19th century, the A.M.E. Church was the first independent black denomination in the United States. Later Turner had pastorates in Baltimore, Maryland, and Washington, DC.

William Douglass (1804–1862) was an abolitionist and Episcopal priest. He preached for peace, racial equality, and education in the religious community.

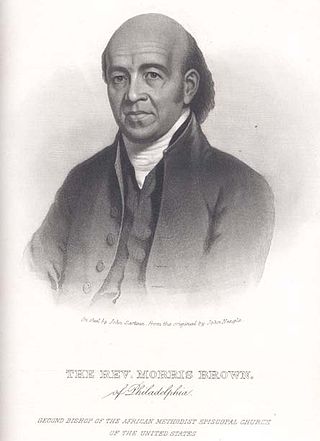

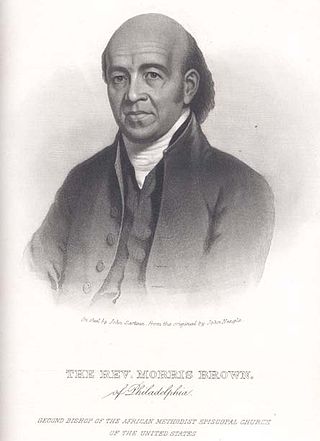

Morris Brown was one of the founders of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and its second presiding bishop. He founded Emanuel AME Church in his native Charleston, South Carolina. It was implicated in the slave uprising planned by Denmark Vesey, also of this church, and after that was suppressed, Brown was imprisoned for nearly a year. He was never convicted of a crime.

James Walker Hood was an African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church bishop in North Carolina from 1872 to 1916. Born and raised in Pennsylvania, he moved to New York and became active in the AME Zion church. Well before the Emancipation Proclamation, he was an active abolitionist.

Edmund Kelly was the first African-American Baptist minister ordained in Tennessee. He escaped slavery in the 1840s to New England and returned after the US Civil War. He worked as a preacher and teacher in Columbia, Tennessee and was a frequent participant in national Baptist Conventions.

John W. Stevenson was an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church minister. He was the financier and builder of the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, DC, which was the largest black church in the country at the time of its building. He was a talented fundraiser and built a number of other churches and was pastor of many churches in Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York, and New England. He was an important figure in the church and eventually held the position of presiding Elder of the New York district.

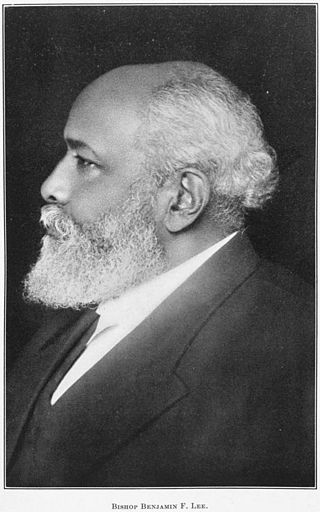

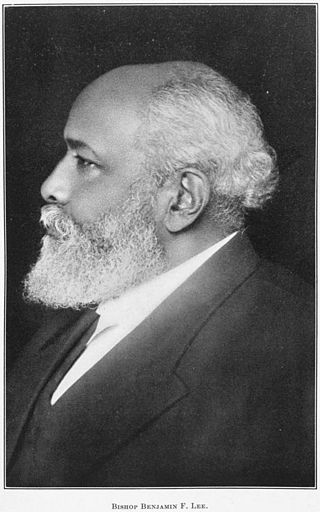

Benjamin Franklin Lee was a religious leader and educator in the United States. He was the president of Wilberforce University from 1876 to 1884. He was editor of the Christian Recorder from 1884 to 1892. He was then elected a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church, serving from 1892 until his resignation in 1921, becoming senior bishop in the church in 1915.

The history of African Americans or Black Philadelphians in the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania has been documented in various sources. People of African descent are currently the largest ethnic group in Philadelphia. Estimates in 2010 by the U.S. Census Bureau documented the total number of people living in Philadelphia who identified as Black or African American at 644,287, or 42.2% of the city's total population.

Rev. Thomas Marcus Decatur Ward was an American preacher, missionary, bishop, and abolitionist who aided African-Americans escaping slavery. Ward is considered to have been a central leader of African American religious activity in the 19th-century and has been referred to as “the original trailblazer of African Methodism” in the United States. In 1854, Ward took over leadership of St. Cyprian's African Methodist Episcopal Church in San Francisco. He was an early representative of the A.M.E. church on the Pacific Coast, and he also served as the 10th Bishop of the A.M.E. Church starting in 1868. Ward often went by the name T. M. D. Ward, but was also known as Thomas Mayers Decatur Ward.

Bishop Singleton T. Jones was a religious leader in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. Although he had little education, Jones taught himself to be an articulate orator and was awarded the position of bishop within the church. Besides being a pastor to churches, he also edited AME Zion publications, the Zion's Standard and Weekly Review and the Discipline.

Harriet Ann Baker was an American evangelist and one of the first African American women to serve as a preacher, in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1914, her mission in Allentown, Pennsylvania, became the home of the St. James AME Zion Church, built in 1936.