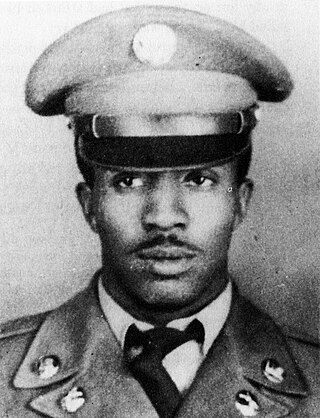

Drafted

During World War II, Daugherty had a job working for the U.S. government in Washington, D.C. for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, and believed that because of this he would not be drafted into the military. However, in December 1943 he received a draft letter ordering him to report for duty; Daugherty was 19 years old at the time. He had very mixed feelings about serving in the military, due to the reality of living under Jim Crow laws that deprived him and other African Americans of many of their civil rights and liberties. He felt that it was difficult for him to justify going to another country to fight for someone else's freedom under the flag of a country that denied him his own. Daugherty, recalling his feelings about being drafted as a second-class citizen, describes thinking: "How dare they draft me and force me to go into a war when I was living in D.C. and had to go to segregated schools... I was fighting for two evils, the Nazis in Germany and my own country that was doing the same kind of things."

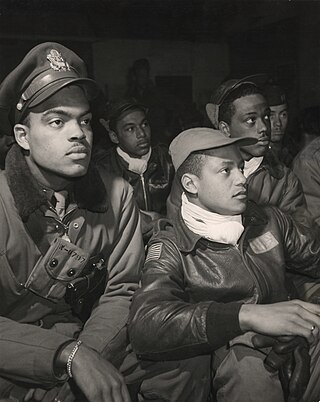

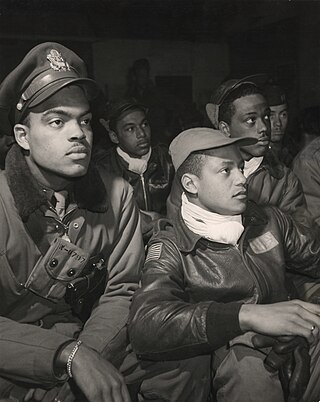

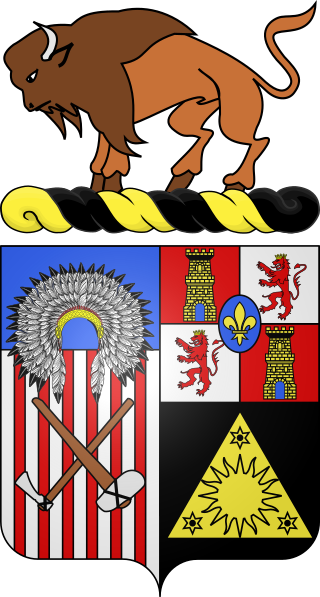

Still, he reported for duty, and was assigned to the all-black 92nd Infantry Division, known from its World War I nickname as the Buffalo Soldiers, a term given to African-American troops by Native Americans during the late 19th century. Although the 92nd had significant casualties, Daugherty recounts how the military did not send replacement troops to keep their numbers up. As units within his division were cut down through attrition, they were forced to continue on without reinforcements. Daugherty recalls asking another soldier why the officers couldn't just call up replacements, and he replied: "Look, bud, they don’t train colored soldiers to fight…they train them to load ships, and you don’t expect them to put white boys in a Negro outfit, do you? What do you think this is, a democracy or something?"

He saw combat action in Italian Campaign during late 1943 and early 1944, including operations in the area between Bologna and Florence. Daugherty expressed the opinion that the 92nd was meant to keep German troops occupied in Italy, preventing them from being deployed to fight against the Soviet Army in eastern Europe, or against the Allied forces moving against the German frontier along the Rhine. This was perceived as a policy of using African-American soldiers in a secondary role, instead of including them in the main thrust in the north.

Daugherty narrowly escaped death after surviving a mortar attack. He describes the surprise that other soldiers had at seeing him walking around afterwards with a bright shard of steel shrapnel, which he had received during the barrage, sticking out of his helmet, and which came within 1/4 of an inch (0.6 cm) from penetrating his skull. [1]

Back home

After the war ended, Daugherty returned to his home in Maryland, and ended up working in the same job at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing that he had held before being drafted. He used money from the G.I. Bill to put himself through college at Howard University, and eventually became the first African American to serve on the local Montgomery County School Board, one of the largest school districts in the U.S. He also had a distinguished career working for the United States Public Health Service in administrative capacities, as well as serving for many years in a governor-appointed position with the Maryland School for the Deaf.

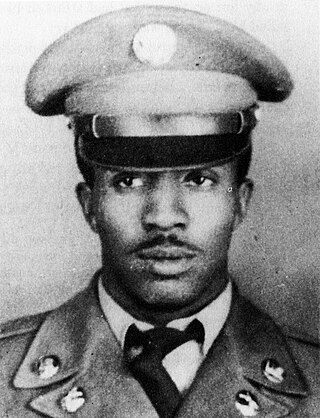

Daugherty describes that he received no hero's welcome after coming home from World War II. Instead, he and the other African Americans who had fought in the war came home to face the same situation that they had left, including legally-sanctioned racial discrimination and segregation. The African American soldiers who served in World War II were overlooked when it came time to hand out medals, [2] and it was not until many years later, and after significant changes in American life and law, that medals began to be awarded to some of the members of the 92nd Infantry Division, some of them posthumously. In 1997 two soldiers from the 92nd finally received the Congressional Medal of Honor from President Bill Clinton. [2] Daugherty himself received the Bronze Star Medal for heroic achievement, and a Combat Infantryman Badge for outstanding performance of duty in action against the enemy.

In his book, Daugherty describes how he chose to face the racism in his country after returning home. He writes: "We are home now though our flame flickers low. Will you fan it with the winds of freedom, or will you smother it with the sands of humiliation? Will it be that we fought for the lesser of two evils? Or is there this freedom and happiness for all men?" Dedicating his life to working in public health to help all people regardless of race or background was how Daugherty chose to respond to this challenge.

Writing his memoirs

As part of his determination to grapple with the struggle of returning home from the war to a Jim Crow America, Daugherty wrote the original manuscript of his autobiography in 1947, two years after the end of World War II. He wrote it down by hand, and his wife Dorothy then typed out numerous copies. She relates how emotional it was for her to do this: "It's like I fought that war, all of the emotions that I experienced—crying, laughing—it was so much a part of me, having done it so many times." [3]

Finally, after years of having the manuscript lying sealed away, in 2009 Daugherty published his autobiography through self-publishing service Xlibris promoted it, including being interviewed on the National Public Radio program All Things Considered . [1] Daugherty expressed in this interview that although he is pleased to see the current situation in the U.S. military where African Americans are not segregated, and can aspire to hold even the highest positions of power and influence within the system, that he still is reluctant to endorse using the military to gain civil rights for people. He firmly stated that: "War is never the answer."

After his book was published, his home town of Silver Spring, Maryland, officially declared July 28 as "Buffalo Soldier James Daugherty Day". [4]

A soldier is a person who is a member of an army. A soldier can be a conscripted or volunteer enlisted person, a non-commissioned officer, a warrant officer, or an officer.

Buffalo Soldiers were United States Army regiments that primarily comprised African Americans, formed during the 19th century to serve on the American frontier. On September 21, 1866, the 10th Cavalry Regiment was formed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The nickname "Buffalo Soldiers" was purportedly given to the regiment by Native Americans who fought against them in the American Indian Wars, and the term eventually became synonymous with all of the African American U.S. Army regiments established in 1866, including the 9th Cavalry Regiment, 10th Cavalry Regiment, 24th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Regiment and 38th Infantry Regiment.

The Combat Infantryman Badge (CIB) is a United States Army military decoration. The badge is awarded to infantrymen and Special Forces soldiers in the rank of colonel and below, who fought in active ground combat while assigned as members of either an Infantry or Special Forces unit of brigade size or smaller at any time after 6 December 1941. For those soldiers who are not members of an infantry, or Special Forces unit, the Combat Action Badge (CAB) is awarded instead. For soldiers with an MOS in the medical field they would, with the exception of a Special Forces Medical Sergeant (18D), receive the Combat Medical Badge. 18D Special Forces Medics would receive the Combat Infantryman badge instead.

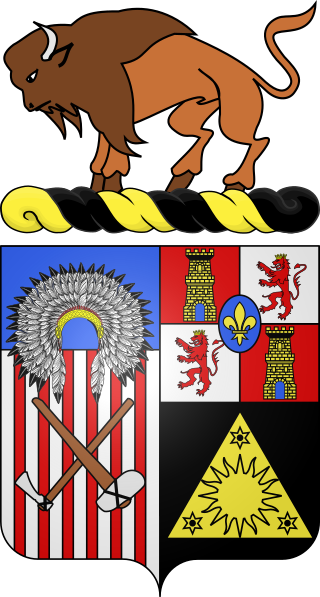

The 92nd Infantry Division was an African-American, later mixed, infantry division of the United States Army that served in World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. The military was racially segregated during the World Wars. The division was organized in October 1917, after the U.S. entry into World War I, at Camp Funston, Kansas, with African-American soldiers from all states. In 1918, before leaving for France, the American buffalo was selected as the divisional insignia due to the "Buffalo Soldiers" nickname, given to African-American cavalrymen in the 19th century. The divisional nickname, "Buffalo Soldiers Division", was inherited from the 366th Infantry, one of the first units organized in the division.

The 93rd Infantry Division was a "colored" segregated unit of the United States Army in World War I and World War II. However, in World War I only its four infantry regiments, two brigade headquarters, and a provisional division headquarters were organized, and the divisional and brigade headquarters were demobilized in May 1918. Its regiments fought primarily under French command in that war. During tough combat in France, they soon acquired from the French the nickname Blue Helmets, as these units were issued horizon blue French Adrian helmets. This referred to the service of several of its units with the French Army during the Second Battle of the Marne. Consequently, its shoulder patch became a blue French helmet, to commemorate its service with the French Army during the German spring offensive.

Joseph Medicine Crow was a Native American writer, historian and war chief of the Crow Tribe. His writings on Native American history and reservation culture are considered seminal works, but he is best known for his writings and lectures concerning the Battle of the Little Bighorn of 1876.

Freddie Stowers was an African-American corporal in the United States Army who was killed in action during World War I while serving in an American unit under French command. Over 70 years later, he posthumously received the Medal of Honor and Purple Heart for his actions.

The 366th Infantry Regiment was an all African American (segregated) unit of the United States Army that served in both World War I and World War II. In the latter war, the unit was exceptional for having all black officers as well as troops. The U.S. military did not desegregate until after World War II. During the war, for most of the segregated units, all field grade and most of the company grade officers were white.

The military history of African Americans spans from the arrival of the first enslaved Africans during the colonial history of the United States to the present day. African Americans have participated in every war fought by or within the United States, including the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the Civil War, the Spanish–American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, the War in Afghanistan, and the Iraq War.

John Robert Fox was a United States Army first lieutenant who was killed in action after calling in artillery fire on the enemy during World War II. In 1997, he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, the nation's highest military decoration for valor, for his actions on December 26, 1944, in the vicinity of Sommocolonia, Italy. It is believed that he called in his own coordinates because he was in an area overrun with German soldiers.

The 10th Cavalry Regiment is a unit of the United States Army. Formed as a segregated African-American unit, the 10th Cavalry was one of the original "Buffalo Soldier" regiments in the post–Civil War Regular Army. It served in combat during the Indian Wars in the western United States, the Spanish–American War in Cuba, Philippine–American War and Mexican Revolution. The regiment was trained as a combat unit but later relegated to non-combat duty and served in that capacity in World War II until its deactivation in 1944.

William Henry Thompson was a United States Army soldier and a posthumous recipient of the United States military's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions in the Korean War.

A Distant Shore: African Americans of D-Day is a television documentary program that was produced for The History Channel by Flight 33 Productions in 2007. Executive Producers were Douglas Cohen, Louis Tarantino and Dolores Gavin. The program was written by Douglas Cohen and produced by Samuel K. Dolan.

World War II in HD is a History Channel television series that chronicles the hardships of World War II, using rare films shot in color never seen on television before. The episodes premiered on five consecutive days in mid-November 2009, with two episodes per day. The series is narrated by Gary Sinise and was produced by Lou Reda Productions in Easton, Pennsylvania.

The 370th Infantry Regiment was the designation for one of the infantry regiments of the 93rd (Provisional) Infantry Division in World War I. Known as the "Black Devils", for their fierce fighting during the First World War and a segregated unit, it was the only United States Army combat unit with African-American officers. In World War II, a regiment known as the 370th Infantry Regiment was part of the segregated 92nd Infantry Division, but did not perpetuate the lineage of the 8th Illinois or World War I 370th, only sharing its numerical designation.

A series of policies were formerly issued by the U.S. military which entailed the separation of white and non-white American soldiers, prohibitions on the recruitment of people of color and restrictions of ethnic minorities to supporting roles. Since the American Revolutionary War, each branch of the United States Armed Forces implemented differing policies surrounding racial segregation. Racial discrimination in the U.S. military was officially opposed by Harry S. Truman's Executive Order 9981 in 1948. The goal was equality of treatment and opportunity. Jon Taylor says, "The wording of the Executive Order was vague because it neither mentioned segregation or integration." Racial segregation was ended in the mid-1950s.

Sommocolonia is a hilltop village in Barga, Lucca, Italy. As of 2022, it had a population of 21. The village was heavily damaged during World War II, where it was the site of a battle between the Wehrmacht and the African American 92nd Infantry Division. The village's population has gradually decreased since the 1930s, as most residents left in search of work.

Royal Lee Bolling was a Massachusetts politician and head of a prominent African-American political family. While serving in the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1965, he sponsored the state's Racial Imbalance Act, which led to the desegregation of Boston's public schools.

Roscoe Conklin "Rock" Cartwright was the United States' second-ever African American U.S. Army brigadier general, third-ever African American U.S. general officer, and the first black field artilleryman promoted to brigadier general.