Benin City serves as the capital and largest metropolitan centre of Edo State, situated in southern Nigeria. Notably, it ranks as the fourth-most populous city in Nigeria, according to the 2006 national census, preceded only by Lagos, Kano, and Ibadan.

The Benin Expedition of 1897 was a punitive expedition by a British force of 1,200 men under Sir Harry Rawson. It came in response to the ambush and slaughter of a 250 strong party led by British Acting Consul General James Phillips of the Niger Coast Protectorate. Rawson's troops captured Benin City and the Kingdom of Benin was eventually absorbed into colonial Nigeria. The expedition freed about 100 Africans enslaved by the Oba.

The Oba of Benin is the traditional ruler and the custodian of the culture of the Edo people and all Edoid people. The then Kingdom of Benin has continued to be mostly populated by the Edo.

The city of Warri is an oil hub within South-South Nigeria and houses an annex of the Delta State Government House. Warri City is one of the major hubs of the petroleum industry in Nigeria. Warri, Udu, Okpe and Uvwie are the commercial capital of Delta State with a population of over 311,970 people in 2006. The city is the indigenous territory of Itsekiri, Urhobo and Ijaw people.

The Benin Bronzes are a group of several thousand metal plaques and sculptures that decorated the royal palace of the Kingdom of Benin, in what is now Edo State, Nigeria. The metal plaques were produced by the Guild of Benin Bronze Casters, now located in Igun Street, also known as Igun-Eronmwon Quarters. Collectively, the objects form the best examples of Benin art and were created from the fourteenth century by artists of the Edo people. The plaques, which in the Edo language are called Ama, depict scenes or represent themes in the history of the kingdom. Apart from the plaques, other sculptures in brass or bronze include portrait heads, jewellery, and smaller pieces.

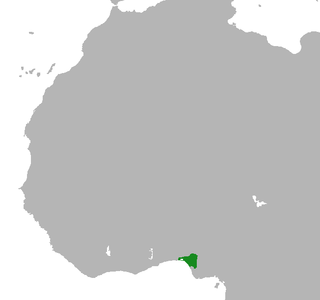

Southern Nigeria was a British protectorate in the coastal areas of modern-day Nigeria formed in 1900 from the union of the Niger Coast Protectorate with territories chartered by the Royal Niger Company below Lokoja on the Niger River.

Lieutenant Colonel Sir Henry Lionel Galway, was a British Army officer and the Governor of South Australia from 18 April 1914 until 30 April 1920. His name was Henry Lionel Gallwey until 1911.

Oba Ovonramwen Nogbaisi, also called Overami, was the thirty-fifth Ọba of the Kingdom of Benin reigning from c. 1888 – c. 1897, up until the British punitive expedition.

Sapele is a primary town and one of the Local Government Areas of Delta State, Nigeria.

Chief Festus Okotie-Eboh was a Nigerian politician who was the finance minister of Nigeria from 1957 to 1966 during the administration of Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa.

Nana Olomu (1852–1916) was an Itsekiri chief and palm oil merchant from the Niger Delta region of southern Nigeria. He was the fourth Itsekiri chief to hold the position of Governor of Benin River.

The Tribal Eye is a seven-part BBC documentary series on the subject of tribal art, written and presented by David Attenborough. It was first transmitted in 1975.

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish a political entity or any group of people outside the borders of the punishing state or union. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong behavior by miscreants, as revenge or corrective action, or to apply strong diplomatic pressure without a formal declaration of war. In the 19th century, punitive expeditions were used more commonly as pretexts for colonial adventures that resulted in annexations, regime changes or changes in policies of the affected state to favour one or more colonial powers.

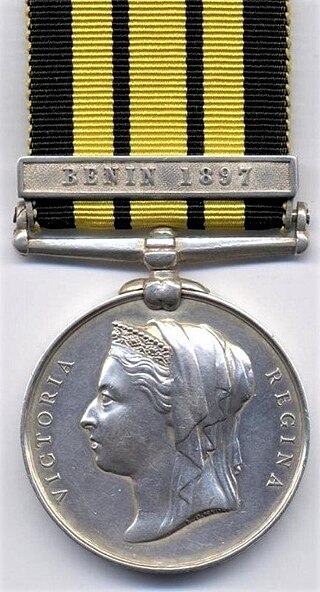

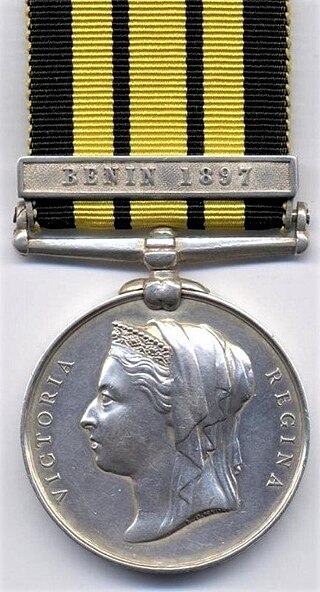

The East and West Africa Medal, established in 1892, was a campaign medal awarded for minor campaigns that took place in East and West Africa between 1887 and 1900. A total of twenty one clasps were issued.

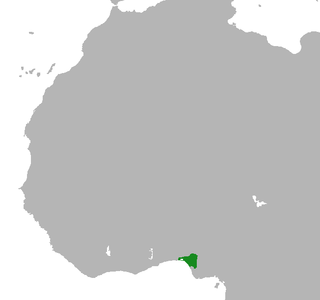

The Kingdom of Benin, also known as Great Benin or Benin Kingdom is a kingdom within what is now considered southern Nigeria. It has no historical relation to the modern republic of Benin, which was known as Dahomey from the 17th century until 1975. The Kingdom of Benin's capital was Edo, now known as Benin City in Edo State, Nigeria. The Benin Kingdom was one of the oldest and most developed states in the coastal hinterland of West Africa. It grew out of the previous Edo Kingdom of Igodomigodo around the 11th century AD, it was annexed by the British Empire in 1897.

An unidentified West African flag was brought to Britain after the Benin Expedition of 1897 against the Kingdom of Benin. Debate exists over the origin of the flag, including which West African people created it. The flag has been considered to be possibly of Itsekiri origin.

Sir Ralph Denham Rayment Moor, was the first high commissioner of the British Southern Nigeria Protectorate.

Lagos Colony was a British colonial possession centred on the port of Lagos in what is now southern Nigeria. Lagos was annexed on 6 August 1861 under the threat of force by Commander Beddingfield of HMS Prometheus who was accompanied by the Acting British Consul, William McCoskry. Oba Dosunmu of Lagos resisted the cession for 11 days while facing the threat of violence on Lagos and its people, but capitulated and signed the Lagos Treaty of Cession. Lagos was declared a colony on 5 March 1862. By 1872, Lagos was a cosmopolitan trading centre with a population over 60,000. In the aftermath of prolonged wars between the mainland Yoruba states, the colony established a protectorate over most of Yorubaland between 1890 and 1897. The protectorate was incorporated into the new Southern Nigeria Protectorate in February 1906, and Lagos became the capital of the Protectorate of Nigeria in January 1914. Since then, Lagos has grown to become the largest city in West Africa, with an estimated metropolitan population of over 9,000,000 as of 2011.

Alan Maxwell Boisragon was a British Army officer, and author, and was Captain Superintendent of the Shanghai Municipal Police from 1901 to 1906.

General Ologbosere, also known as Chief Irabor, resisted the conquest of Benin Empire before he was captured and killed.