An extremophile is an organism that is able to live in extreme environments, i.e., environments with conditions approaching or stretching the limits of what known life can adapt to, such as extreme temperature, pressure, radiation, salinity, or pH level.

Bacterial growth is proliferation of bacterium into two daughter cells, in a process called binary fission. Providing no mutation event occurs, the resulting daughter cells are genetically identical to the original cell. Hence, bacterial growth occurs. Both daughter cells from the division do not necessarily survive. However, if the surviving number exceeds unity on average, the bacterial population undergoes exponential growth. The measurement of an exponential bacterial growth curve in batch culture was traditionally a part of the training of all microbiologists; the basic means requires bacterial enumeration by direct and individual, direct and bulk (biomass), indirect and individual, or indirect and bulk methods. Models reconcile theory with the measurements.

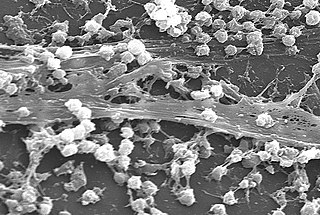

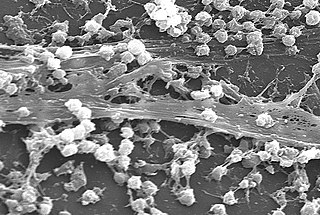

A biofilm is a syntrophic community of microorganisms in which cells stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy extracellular matrix that is composed of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs). The cells within the biofilm produce the EPS components, which are typically a polymeric combination of extracellular polysaccharides, proteins, lipids and DNA. Because they have a three-dimensional structure and represent a community lifestyle for microorganisms, they have been metaphorically described as "cities for microbes".

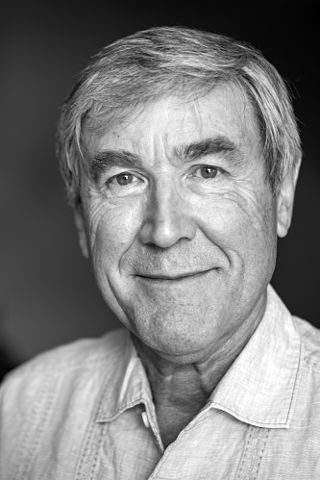

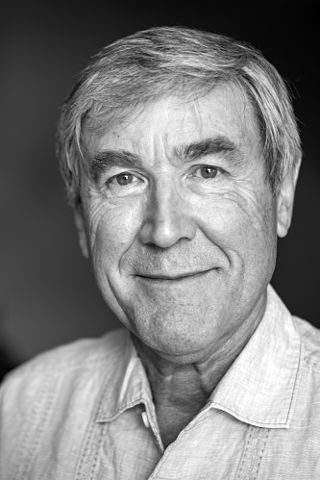

Paul Charles William Davies is an English physicist, writer and broadcaster, a professor in Arizona State University and director of BEYOND: Center for Fundamental Concepts in Science. He is affiliated with the Institute for Quantum Studies in Chapman University in California. He previously held academic appointments in the University of Cambridge, University College London, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, University of Adelaide and Macquarie University. His research interests are in the fields of cosmology, quantum field theory, and astrobiology.

Methylotrophs are a diverse group of microorganisms that can use reduced one-carbon compounds, such as methanol or methane, as the carbon source for their growth; and multi-carbon compounds that contain no carbon-carbon bonds, such as dimethyl ether and dimethylamine. This group of microorganisms also includes those capable of assimilating reduced one-carbon compounds by way of carbon dioxide using the ribulose bisphosphate pathway. These organisms should not be confused with methanogens which on the contrary produce methane as a by-product from various one-carbon compounds such as carbon dioxide. Some methylotrophs can degrade the greenhouse gas methane, and in this case they are called methanotrophs. The abundance, purity, and low price of methanol compared to commonly used sugars make methylotrophs competent organisms for production of amino acids, vitamins, recombinant proteins, single-cell proteins, co-enzymes and cytochromes.

The arsenate is an ion with the chemical formula AsO3−4. Bonding in arsenate consists of a central arsenic atom, with oxidation state +5, double bonded to one oxygen atom and single bonded to a further three oxygen atoms. The four oxygen atoms orient around the arsenic atom in a tetrahedral geometry. Resonance disperses the ion's −3 charge across all four oxygen atoms.

In microbiology, the phyllosphere is the total above-ground surface of a plant when viewed as a habitat for microorganisms. The phyllosphere can be further subdivided into the caulosphere (stems), phylloplane (leaves), anthosphere (flowers), and carposphere (fruits). The below-ground microbial habitats are referred to as the rhizosphere and laimosphere. Most plants host diverse communities of microorganisms including bacteria, fungi, archaea, and protists. Some are beneficial to the plant, while others function as plant pathogens and may damage the host plant or even kill it.

The Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology is a research institute for terrestrial microbiology in Marburg, Germany. It was founded in 1991 by Rudolf K. Thauer and is one of 80 institutes in the Max Planck Society (Max-Planck-Gesellschaft). Its sister institute is the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, which was founded a year later in 1992 in Bremen.

Bacteria are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among the first life forms to appear on Earth, and are present in most of its habitats. Bacteria inhabit the air, soil, water, acidic hot springs, radioactive waste, and the deep biosphere of Earth's crust. Bacteria play a vital role in many stages of the nutrient cycle by recycling nutrients and the fixation of nitrogen from the atmosphere. The nutrient cycle includes the decomposition of dead bodies; bacteria are responsible for the putrefaction stage in this process. In the biological communities surrounding hydrothermal vents and cold seeps, extremophile bacteria provide the nutrients needed to sustain life by converting dissolved compounds, such as hydrogen sulphide and methane, to energy. Bacteria also live in mutualistic, commensal and parasitic relationships with plants and animals. Most bacteria have not been characterised and there are many species that cannot be grown in the laboratory. The study of bacteria is known as bacteriology, a branch of microbiology.

Felisa Wolfe-Simon is an American microbial geobiologist and biogeochemist. In 2010, Wolfe-Simon led a team that discovered GFAJ-1, an extremophile bacterium that they claimed was capable of substituting arsenic for a small percentage of its phosphorus to sustain its growth, thus advancing the remarkable possibility of non-RNA/DNA-based genetics. However, these conclusions were immediately debated and criticized in correspondence to the original journal of publication, and were widely disbelieved by scientists. In 2012, two reports refuting the most significant aspects of the original results were published in the same journal in which the original findings had been previously published.

Arsenic biochemistry refers to biochemical processes that can use arsenic or its compounds, such as arsenate. Arsenic is a moderately abundant element in Earth's crust, and although many arsenic compounds are often considered highly toxic to most life, a wide variety of organoarsenic compounds are produced biologically and various organic and inorganic arsenic compounds are metabolized by numerous organisms. This pattern is general for other related elements, including selenium, which can exhibit both beneficial and deleterious effects. Arsenic biochemistry has become topical since many toxic arsenic compounds are found in some aquifers, potentially affecting many millions of people via biochemical processes.

GFAJ-1 is a strain of rod-shaped bacteria in the family Halomonadaceae. It is an extremophile that was isolated from the hypersaline and alkaline Mono Lake in eastern California by geobiologist Felisa Wolfe-Simon, a NASA research fellow in residence at the US Geological Survey. In a 2010 Science journal publication, the authors claimed that the microbe, when starved of phosphorus, is capable of substituting arsenic for a small percentage of its phosphorus to sustain its growth. Immediately after publication, other microbiologists and biochemists expressed doubt about this claim, which was robustly criticized in the scientific community. Subsequent independent studies published in 2012 found no detectable arsenate in the DNA of GFAJ-1, refuted the claim, and demonstrated that GFAJ-1 is simply an arsenate-resistant, phosphate-dependent organism.

Bacterial morphological plasticity refers to changes in the shape and size that bacterial cells undergo when they encounter stressful environments. Although bacteria have evolved complex molecular strategies to maintain their shape, many are able to alter their shape as a survival strategy in response to protist predators, antibiotics, the immune response, and other threats.

Arsenate-reducing bacteria are bacteria which reduce arsenates. Arsenate-reducing bacteria are ubiquitous in arsenic-contaminated groundwater (aqueous environment). Arsenates are salts or esters of arsenic acid (H3AsO4), consisting of the ion AsO43−. They are moderate oxidizers that can be reduced to arsenites and to arsine. Arsenate can serve as a respiratory electron acceptor for oxidation of organic substrates and H2S or H2. Arsenates occur naturally in minerals such as adamite, alarsite, legrandite, and erythrite, and as hydrated or anhydrous arsenates. Arsenates are similar to phosphates since arsenic (As) and phosphorus (P) occur in group 15 (or VA) of the periodic table. Unlike phosphates, arsenates are not readily lost from minerals due to weathering. They are the predominant form of inorganic arsenic in aqueous aerobic environments. On the other hand, arsenite is more common in anaerobic environments, more mobile, and more toxic than arsenate. Arsenite is 25–60 times more toxic and more mobile than arsenate under most environmental conditions. Arsenate can lead to poisoning, since it can replace inorganic phosphate in the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate --> 1,3-biphosphoglycerate step of glycolysis, producing 1-arseno-3-phosphoglycerate instead. Although glycolysis continues, 1 ATP molecule is lost. Thus, arsenate is toxic due to its ability to uncouple glycolysis. Arsenate can also inhibit pyruvate conversion into acetyl-CoA, thereby blocking the TCA cycle, resulting in additional loss of ATP.

Rosemary Jeanne Redfield is a microbiologist associated with the University of British Columbia where she worked as a faculty member in the Department of Zoology from 1993 until retiring in 2021.

Mary E. Lidstrom is a Professor of Microbiology at the University of Washington. She also holds the Frank Jungers Chair of Engineering, in the Department of Chemical Engineering. She currently is a fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology, a member of the National Academy of Sciences and serves on the editorial boards of the Journal of Bacteriology and FEMS Microbial Ecology.

Abigail A. Salyers was a microbiologist who pioneered the field of human microbiome research. Her work on the bacterial phylum Bacteroidetes and its ecology led to a better understanding of antibiotic resistance and mobile genetic elements. At a time where the prevailing paradigm was focused on E. coli as a model organism, Salyers emphasized the importance of investigating the breadth of microbial diversity. She was one of the first to conceptualize the human body as a microbial ecosystem. Over the course of her 40-year career, she was presented with numerous awards for teaching and research and an honorary degree from ETH Zurich, and served as president of the American Society for Microbiology.

The plant microbiome, also known as the phytomicrobiome, plays roles in plant health and productivity and has received significant attention in recent years. The microbiome has been defined as "a characteristic microbial community occupying a reasonably well-defined habitat which has distinct physio-chemical properties. The term thus not only refers to the microorganisms involved but also encompasses their theatre of activity".

Some microorganisms, such as endophytes, penetrate and occupy the plant internal tissues, forming the endospheric microbiome. The arbuscular mycorrhizal and other endophytic fungi are the dominant colonizers of the endosphere. Bacteria, and to some degree archaea, are important members of endosphere communities. Some of these endophytic microbes interact with their host and provide obvious benefits to plants. Unlike the rhizosphere and the rhizoplane, the endospheres harbor highly specific microbial communities. The root endophytic community can be very distinct from that of the adjacent soil community. In general, diversity of the endophytic community is lower than the diversity of the microbial community outside the plant. The identity and diversity of the endophytic microbiome of above-and below-ground tissues may also differ within the plant.

Shimshon Belkin is an environmental microbiologist, a Professor Emeritus at the Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences at the Alexander Silberman Institute of Life Sciences of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel.