Related Research Articles

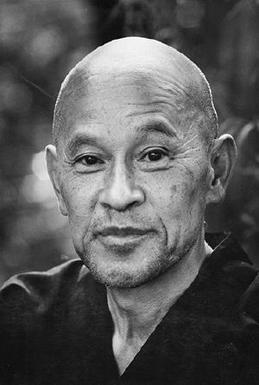

Shunryu Suzuki was a Sōtō Zen monk and teacher who helped popularize Zen Buddhism in the United States, and is renowned for founding the first Zen Buddhist monastery outside Asia. Suzuki founded San Francisco Zen Center which, along with its affiliate temples, comprises one of the most influential Zen organizations in the United States. A book of his teachings, Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind, is one of the most popular books on Zen and Buddhism in the West.

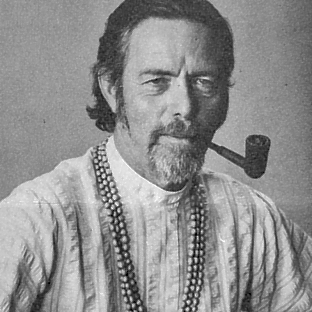

Alan Wilson Watts was a British and American writer, speaker, and self-styled "philosophical entertainer", known for interpreting and popularising Buddhist, Taoist, and Hindu philosophy for a Western audience.

Buddhism in the West broadly encompasses the knowledge and practice of Buddhism outside of Asia, in the Western world. Occasional intersections between Western civilization and the Buddhist world have been occurring for thousands of years. Greek colonies existed in India during the Buddha's life, as early as the 6th century. The first Westerners to become Buddhists were Greeks who settled in Bactria and India during the Hellenistic period. They became influential figures during the reigns of the Indo-Greek kings, whose patronage of Buddhism led to the emergence of Greco-Buddhism and Greco-Buddhist art.

Kenshō is an East Asian Buddhist term from the Chan / Zen tradition which means "seeing" or "perceiving" "nature" or "essence", or 'true face'. It is usually translated as "seeing one's [true] nature," with "nature" referring to buddha-nature, ultimate reality, the Dharmadhatu. The term appears in one of the classic slogans which define Chan Buddhism: to see oneʼs own nature and accomplish Buddhahood (見性成佛).

Geshe Kelsang Gyatso was a Buddhist monk, meditation teacher, scholar, and author. He was the founder and spiritual director of the New Kadampa Tradition-International Kadampa Buddhist Union (Function), a registered non-profit, modern Buddhist organization that came out of the Gelugpa school/lineage. They have 1,300 centres around the world, including temples, city temples and retreat centres that offer an accessible approach to ancient wisdom.

Hōun Jiyu-Kennett, born Peggy Teresa Nancy Kennett, was a British roshi most famous for having been the first female to be sanctioned by the Sōtō School of Japan to teach in the West.

JikaiDainin Katagiri, was a Sōtō Zen priest and teacher, and the founding abbot of Minnesota Zen Meditation Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where he served from 1972 until his death from cancer in 1990. He is also the founder of Hokyoji Zen Practice Community in Eitzen, Minnesota. Before becoming first abbot of the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center, Katagiri had worked at the Zenshuji Soto Zen Mission in Los Angeles and had also been of great service to Shunryu Suzuki at the San Francisco Zen Center, particularly from 1969 until Suzuki's death in 1971. Katagiri was important in helping bring Zen Buddhism from Japan to the United States during its formative years. He is also the credited author of several books compiled from his talks.

The term American Buddhism can be used to describe all Buddhist groups within the United States, including Asian-American Buddhists born into the faith, who comprise the largest percentage of Buddhists in the country.

Zen at War is a book written by Brian Daizen Victoria, first published in 1997. The second edition appeared in 2006.

Dennis Merzel is an American Zen and spirituality teacher, also known as Genpo Roshi.

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen Buddhism, an originally Chinese Mahāyāna school of Buddhism that strongly emphasizes dhyā

Shōhaku Okumura is a Japanese Sōtō Zen priest and the founder and abbot of the Sanshin Zen Community located in Bloomington, Indiana, where he and his family currently live. From 1997 until 2010, Okumura also served as director of the Sōtō Zen Buddhism International Center in San Francisco, California, which is an administrative office of the Sōtō school of Japan.

Zenkei Blanche Hartman was a Soto Zen teacher practicing in the lineage of Shunryu Suzuki. From 1996 to 2002 she served two terms as co-abbess of the San Francisco Zen Center. She was the first woman to assume such a leadership position at the center. A member of the American Zen Teachers Association, Blanche was especially known for her expertise in the ancient ritual of sewing a kesa. Hartman became known for her attention to issues faced by women; she and her late husband Lou Hartman had four children, eight grandchildren, and a number of great-grandchildren.

Bonnie Myotai Treace is a Zen teacher and priest, the founder of Hermitage Heart, and formerly the abbot of the Zen Center of New York City (ZCNYC). She teaches currently in Black Mountain and Asheville, North Carolina. Myotai Sensei is the first Dharma successor of John Daido Loori, Roshi, in the Mountains and Rivers Order (MRO), having received shiho, dharma transmission, from him in 1996. Serving and training for over two decades in the MRO, she was the establishing teacher and first abbess of the ZCNYC. At the Monastery she was the Vice Abbot, the first director of Dharma Communications, editor of Mountain Record, and coordinator of the affiliates of the MRO. Treace, ordained as a Zen monastic, now lives as a lay teacher, working primarily with her long-term students.

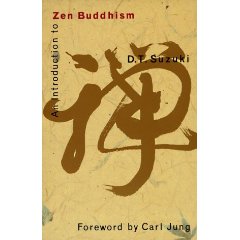

An Introduction to Zen Buddhism is a 1934 book about Zen Buddhism by Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki. First published in Kyoto by the Eastern Buddhist Society, it was soon published in other nations and languages, with an added preface by Carl Jung. The book has come to be regarded as "one of the most influential books on Zen in the West".

Zen was introduced in the United States at the end of the 19th century by Japanese teachers who went to America to serve groups of Japanese immigrants and become acquainted with the American culture. After World War II, interest from non-Asian Americans grew rapidly. This resulted in the commencement of an indigenous American Zen tradition which also influences the larger western (Zen) world.

Shundo Aoyama Rōshi is a Japanese Buddhist nun and abbess. She is the first nun to be appointed to the rank of Daikyoshi in the Soto Zen school.

The Zen boom was a rise in interest in Zen practices in North America, Europe, and elsewhere around the world beginning in the 1950s and continuing into the 1970s. Zen was seen as an alluring philosophical practice that acted as a tranquilizing agent against the memory of World War II, active Cold War conflicts, nuclear anxieties, and other social injustices. The surge in interest is thought to have been heavily influenced by lectures on Zen given by D.T. Suzuki at Columbia University from 1950 to 1958, as well as his many books on the subject. Authors like Ruth Fuller Sasaki and Gary Snyder also traveled to Japan to formally study Zen Buddhism. Snyder would influence fellow Beat poets from Allen Ginsberg, and Jack Kerouac, to Philip Whalen, to also follow his interest in Zen. Alan Watts also published his classic book The Way of Zen as a guide to Zen intended for western audiences.

References

- ↑ "Lecture on Nothing by KAY LARSON, art critic, columnist and author (New York)". Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ratliff, Ben (July 22, 2012). "Listening to the Void, Vital and Profound". The New York Times . Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Popova, Maria (July 5, 2012). "Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists". Brain Pickings. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ↑ Spencer, Cleo (March 15, 2013). "Art Critic Alum Praises Subjectivity in Art Writing". The Student Life . Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ↑ "Kay Larson | HuffPost". www.huffpost.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ↑ Where the Heart Beats. Kirkus Reviews. April 21, 2012.

- ↑ Dorrity, Marx. "Book Review: Where the Heart Beats". Chronogram Magazine. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ↑ Swed, Mark (July 22, 2012). "Review: Kay Larson's inspirational 'Where the Heart Beats'". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ↑ "Where the Heart Beats by Kay Larson: 9780143123477 | PenguinRandomHouse.com: Books". PenguinRandomhouse.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ↑ "Staff Picks: Our Favorite Music Books Of 2012". NPR.org. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ↑ Duersten, Matthew (December 19, 2012). "Top 10 Music Books of 2012 Los Angeles Magazine". Los Angeles Magazine . Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ↑ "The New York Times - Search". www.nytimes.com. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Kay Larson". kaylarson.com. March 28, 2022.

- ↑ Kowinski, William Severini (March 10, 2005). "Kowincidence: AWAKE: Art, Buddhism and the Dimensions of Consciousness". Kowincidence. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ↑ Buddha mind in contemporary art. Jacquelynn Baas, Mary Jane Jacob. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2004. ISBN 0-520-24346-3. OCLC 55738266.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)