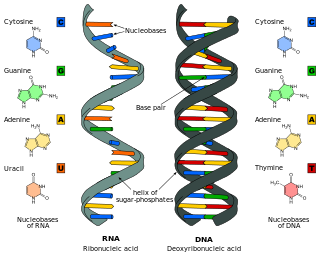

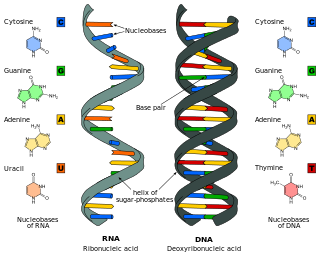

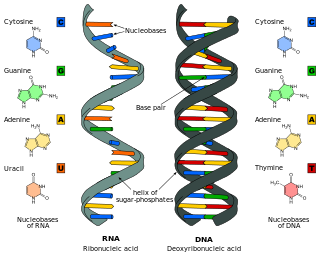

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nucleic acids are deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA). If the sugar is ribose, the polymer is RNA; if the sugar is the ribose derivative deoxyribose, the polymer is DNA.

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules within all life-forms on Earth. Nucleotides are obtained in the diet and are also synthesized from common nutrients by the liver.

Pyrimidine is an aromatic, heterocyclic, organic compound similar to pyridine. One of the three diazines, it has nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 3 in the ring. The other diazines are pyrazine and pyridazine.

Adenine is a nucleobase. It is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The three others are guanine, cytosine and thymine. Its derivatives have a variety of roles in biochemistry including cellular respiration, in the form of both the energy-rich adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and the cofactors nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) and Coenzyme A. It also has functions in protein synthesis and as a chemical component of DNA and RNA. The shape of adenine is complementary to either thymine in DNA or uracil in RNA.

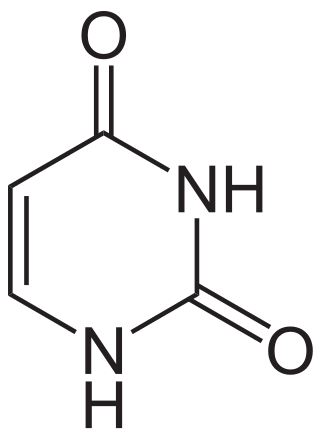

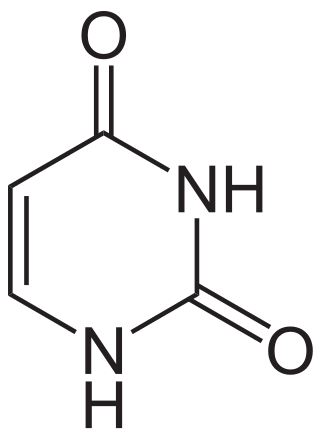

Uracil is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid RNA. The others are adenine (A), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). In RNA, uracil binds to adenine via two hydrogen bonds. In DNA, the uracil nucleobase is replaced by thymine (T). Uracil is a demethylated form of thymine.

In organic chemistry, a dicarbonyl is a molecule containing two carbonyl groups. Although this term could refer to any organic compound containing two carbonyl groups, it is used more specifically to describe molecules in which both carbonyls are in close enough proximity that their reactivity is changed, such as 1,2-, 1,3-, and 1,4-dicarbonyls. Their properties often differ from those of monocarbonyls, and so they are usually considered functional groups of their own. These compounds can have symmetrical or unsymmetrical substituents on each carbonyl, and may also be functionally symmetrical or unsymmetrical.

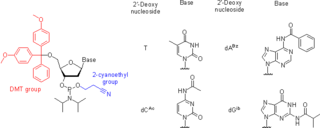

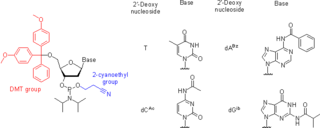

Nucleoside phosphoramidites are derivatives of natural or synthetic nucleosides. They are used to synthesize oligonucleotides, relatively short fragments of nucleic acid and their analogs. Nucleoside phosphoramidites were first introduced in 1981 by Beaucage and Caruthers. To avoid undesired side reactions, reactive hydroxy and exocyclic amino groups present in natural or synthetic nucleosides are appropriately protected. As long as a nucleoside analog contains at least one hydroxy group, the use of the appropriate protecting strategy allows one to convert that to the respective phosphoramidite and to incorporate the latter into synthetic nucleic acids. To be incorporated in the middle of an oligonucleotide chain using phosphoramidite strategy, the nucleoside analog must possess two hydroxy groups or, less often, a hydroxy group and another nucleophilic group (amino or mercapto). Examples include, but are not limited to, alternative nucleotides, LNA, morpholino, nucleosides modified at the 2'-position (OMe, protected NH2, F), nucleosides containing non-canonical bases (hypoxanthine and xanthine contained in natural nucleosides inosine and xanthosine, respectively, tricyclic bases such as G-clamp, etc.) or bases derivatized with a fluorescent group or a linker arm.

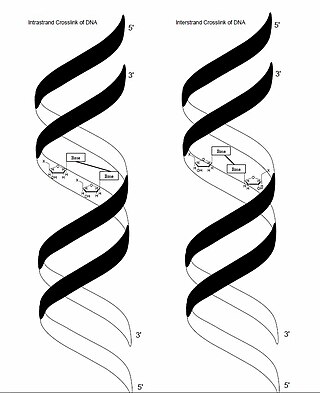

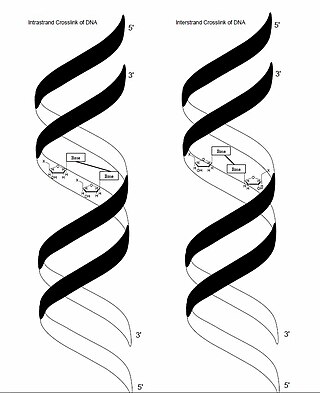

In genetics, crosslinking of DNA occurs when various exogenous or endogenous agents react with two nucleotides of DNA, forming a covalent linkage between them. This crosslink can occur within the same strand (intrastrand) or between opposite strands of double-stranded DNA (interstrand). These adducts interfere with cellular metabolism, such as DNA replication and transcription, triggering cell death. These crosslinks can, however, be repaired through excision or recombination pathways.

The hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozyme is a non-coding RNA found in the hepatitis delta virus that is necessary for viral replication and is the only known human virus that utilizes ribozyme activity to infect its host. The ribozyme acts to process the RNA transcripts to unit lengths in a self-cleavage reaction during replication of the hepatitis delta virus, which is thought to propagate by a double rolling circle mechanism. The ribozyme is active in vivo in the absence of any protein factors and was the fastest known naturally occurring self-cleaving RNA at the time of its discovery.

In enzymology, a tRNA (guanine-N2-)-methyltransferase (EC 2.1.1.32) is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction

Nucleic acid analogues are compounds which are analogous to naturally occurring RNA and DNA, used in medicine and in molecular biology research. Nucleic acids are chains of nucleotides, which are composed of three parts: a phosphate backbone, a pentose sugar, either ribose or deoxyribose, and one of four nucleobases. An analogue may have any of these altered. Typically the analogue nucleobases confer, among other things, different base pairing and base stacking properties. Examples include universal bases, which can pair with all four canonical bases, and phosphate-sugar backbone analogues such as PNA, which affect the properties of the chain . Nucleic acid analogues are also called Xeno Nucleic Acid and represent one of the main pillars of xenobiology, the design of new-to-nature forms of life based on alternative biochemistries.

Ribonuclease pancreatic is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the RNASE1 gene.

Experimental approaches of determining the structure of nucleic acids, such as RNA and DNA, can be largely classified into biophysical and biochemical methods. Biophysical methods use the fundamental physical properties of molecules for structure determination, including X-ray crystallography, NMR and cryo-EM. Biochemical methods exploit the chemical properties of nucleic acids using specific reagents and conditions to assay the structure of nucleic acids. Such methods may involve chemical probing with specific reagents, or rely on native or analogue chemistry. Different experimental approaches have unique merits and are suitable for different experimental purposes.

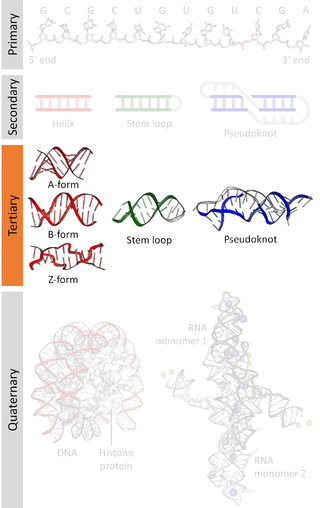

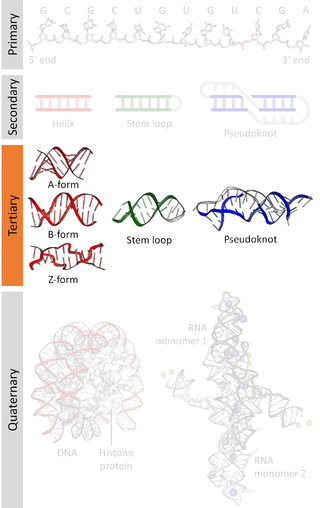

Nucleic acid tertiary structure is the three-dimensional shape of a nucleic acid polymer. RNA and DNA molecules are capable of diverse functions ranging from molecular recognition to catalysis. Such functions require a precise three-dimensional structure. While such structures are diverse and seemingly complex, they are composed of recurring, easily recognizable tertiary structural motifs that serve as molecular building blocks. Some of the most common motifs for RNA and DNA tertiary structure are described below, but this information is based on a limited number of solved structures. Many more tertiary structural motifs will be revealed as new RNA and DNA molecules are structurally characterized.

Nucleic acid structure refers to the structure of nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA. Chemically speaking, DNA and RNA are very similar. Nucleic acid structure is often divided into four different levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary.

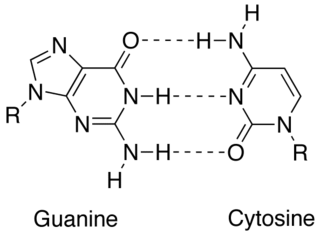

Nucleic acid secondary structure is the basepairing interactions within a single nucleic acid polymer or between two polymers. It can be represented as a list of bases which are paired in a nucleic acid molecule. The secondary structures of biological DNAs and RNAs tend to be different: biological DNA mostly exists as fully base paired double helices, while biological RNA is single stranded and often forms complex and intricate base-pairing interactions due to its increased ability to form hydrogen bonds stemming from the extra hydroxyl group in the ribose sugar.

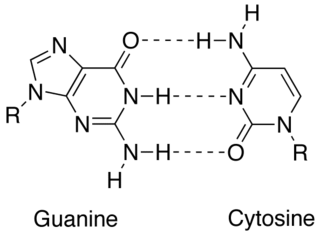

In molecular biology, complementarity describes a relationship between two structures each following the lock-and-key principle. In nature complementarity is the base principle of DNA replication and transcription as it is a property shared between two DNA or RNA sequences, such that when they are aligned antiparallel to each other, the nucleotide bases at each position in the sequences will be complementary, much like looking in the mirror and seeing the reverse of things. This complementary base pairing allows cells to copy information from one generation to another and even find and repair damage to the information stored in the sequences.

Nucleic acid NMR is the use of nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to obtain information about the structure and dynamics of nucleic acid molecules, such as DNA or RNA. It is useful for molecules of up to 100 nucleotides, and as of 2003, nearly half of all known RNA structures had been determined by NMR spectroscopy.

rRNA endonuclease is an enzyme that catalyses the hydrolysis of the phosphodiester linkage between guanosine and adenosine residues at one specific position in the 28S rRNA of rat ribosomes. This enzyme also acts on bacterial rRNA.

i-motif DNA, short for intercalated-motif DNA, are cytosine-rich four-stranded quadruplex DNA structures, similar to the G-quadruplex structures that are formed in guanine-rich regions of DNA.