The Cambodian–Vietnamese War was an armed conflict between Democratic Kampuchea, controlled by Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge, and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. The war began with repeated attacks by the Kampuchea Revolutionary Army on the southwestern border of Vietnam, particularly the Ba Chúc massacre which resulted in the deaths of over 3,000 Vietnamese civilians. On 23 December 1978, 10 out of 19 of the Khmer Rouge's military divisions opened fire along the border with Vietnam with the goal of invading the Vietnamese provinces of Đồng Tháp, An Giang and Kiên Giang. On 25 December 1978, Vietnam launched a full-scale invasion of Kampuchea, occupying the country in two weeks and removing the government of the Communist Party of Kampuchea from power. In doing so, Vietnam put an ultimate stop to the Cambodian genocide, which had most likely killed between 1.2 million and 2.8 million people — or between 13 and 30 percent of the country’s population. On 7 January 1979, the Vietnamese captured Phnom Penh, which forced Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge to retreat back into the jungle near the border with Thailand.

The Khmer People's National Liberation Front was a political front organized in 1979 in opposition to the Vietnamese-installed People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) regime in Cambodia. The 200,000 Vietnamese troops supporting the PRK, as well as Khmer Rouge defectors, had ousted the Democratic Kampuchea regime of Pol Pot, and were initially welcomed by the majority of Cambodians as liberators. Some Khmer, though, recalled the two countries' historical rivalry and feared that the Vietnamese would attempt to subjugate the country, and began to oppose their military presence. Members of the KPNLF supported this view.

The Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea, renamed in 1990 to the National Government of Cambodia, was a coalition government in exile composed of three Cambodian political factions, namely Prince Norodom Sihanouk's FUNCINPEC party, the Party of Democratic Kampuchea and the Khmer People's National Liberation Front (KPNLF) formed in 1982, broadening the de facto deposed Democratic Kampuchea regime. For most of its existence, it was the internationally recognized government of Cambodia.

The MOULINAKA was a pro-Sihanouk military organization formed in August 1979 by an armed group on the Thai-Cambodian border.

Son Sann was a Cambodian politician and anti-communist resistance leader who served as the 22nd Prime Minister of Cambodia (1967–68) and later as President of the National Assembly (1993). A devout Buddhist, he was married and fathered seven children. His full honorary title is "Samdech Borvor Setha Thipadei Son Sann".

The Khmer Serei were an anti-communist and anti-monarchist guerrilla force founded by Cambodian nationalist Son Ngoc Thanh. In 1959, he published 'The Manifesto of the Khmer Serei' claiming that Sihanouk was supporting the 'communization' of Kampuchea. In the 1960s, the Khmer Serei were growing in numbers, hoping to become a major political and fighting force.

FCU – UNTAC, the Force Communications Unit UNTAC, was the Australian component of the UNTAC mission in Cambodia.

The National Army of Democratic Kampuchea (NADK) was a Cambodian guerrilla force. NADK were the armed forces of the Party of Democratic Kampuchea also known as "Khmer Rouge", operating between 1979 and the late 1990s.

The People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) was a partially recognised state in Southeast Asia which existed from 1979 to 1989. It was a satellite state of Vietnam, founded in Cambodia by the Vietnamese-backed Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation, a group of Cambodian communists who were dissatisfied with the Khmer Rouge due to its oppressive rule and defected from it after the overthrow of Democratic Kampuchea, Pol Pot's government. Brought about by an invasion from Vietnam, which routed the Khmer Rouge armies, it had Vietnam and the Soviet Union as its main allies.

After the 1978 Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia and subsequent collapse of Democratic Kampuchea in 1979, the Khmer Rouge fled to the border regions of Thailand, and, with assistance from China, Pol Pot's troops managed to regroup and reorganize in forested and mountainous zones on the Thai-Cambodian border. During the 1980s and early 1990s Khmer Rouge forces operated from inside refugee camps in Thailand, in an attempt to de-stabilize the pro-Hanoi People's Republic of Kampuchea's government, which Thailand refused to recognise. Thailand and Vietnam faced off across the Thai-Cambodian border with frequent Vietnamese incursions and shellings into Thai territory throughout the 1980s in pursuit of Cambodian guerrillas who kept attacking Vietnamese occupation forces.

The earliest traces of armed conflict in the territory that constitutes modern Cambodia date to the Iron Age settlement of Phum Snay in north-western Cambodia.

General Sak Sutsakhan was a Cambodian politician and soldier who had a long career in the country's politics. He was the last Head of State of the Khmer Republic, the regime overthrown by the Khmer Rouge in 1975. Sak Sutsakhan formed a pro-US force known as the Khmer Sâ. As a businessman, Sak Sutsakhan notably owned a Dairy Queen franchise in Anaheim, California.

General Dien Del was a prominent Cambodian military officer and later, politician. He directed combat operations in Cambodia, first as a general in the Army of the Khmer Republic (1970–1975) and then as a leader of Khmer People's National Liberation Front (KPNLF) guerrilla forces fighting against the Vietnamese occupation (1979–1992). Following Vietnam's withdrawal from Cambodia in 1990, he presided over the demobilization of the KPNLF's armed forces in February 1992. In 1998 he was elected to the National Legislative Assembly as a member of FUNCINPEC. He spent the last fifteen years of his career as advisor to the Cambodian government.

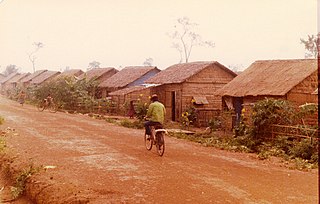

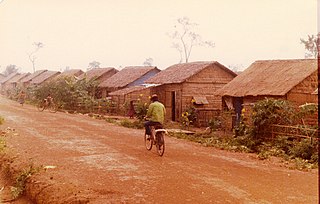

Site Two Refugee Camp was the largest refugee camp on the Thai-Cambodian border and, for several years, the largest refugee camp in Southeast Asia. The camp was established in January 1985 during the 1984-1985 Vietnamese dry-season offensive against guerrilla forces opposing Vietnam's occupation of Cambodia.

Nong Samet Refugee Camp, in Nong Samet Village, Khok Sung District, Sa Kaeo Province, Thailand, was a refugee camp on the Thai-Cambodian border and served as a power base for the Khmer People's National Liberation Front (KPNLF) until its destruction by the Vietnamese military in late 1984.

Nong Chan Refugee Camp, in Nong Chan Village, Khok Sung District, Sa Kaeo Province, Thailand, was one of the earliest organized refugee camps on the Thai-Cambodian border, where thousands of Khmer refugees sought food and health care after fleeing the Cambodian-Vietnamese War. It was destroyed by the Vietnamese military in late 1984, after which its population was transferred to Site Two Refugee Camp.

The K5 Plan, K5 Belt or K5 Project, also known as the Bamboo Curtain, was an attempt between 1985 and 1989 by the government of the People's Republic of Kampuchea to seal Khmer Rouge guerrilla infiltration routes into Cambodia by means of trenches, wire fences, and minefields along virtually the entire Cambodia–Thailand border.

The Cambodian humanitarian crisis from 1969 to 1993 consisted of a series of related events which resulted in the death, displacement, or resettlement abroad of millions of Cambodians.

The Dangrek genocide, also known as the Preah Vihear pushback, is a border incident which took place along the Dangrek Mountain Range on the Thai-Cambodian border which resulted in the death of many mostly Sino-Khmer refugees who were refused asylum by the Kingdom of Thailand in June 1979.

The Cambodian conflict, also known as the Khmer Rouge insurgency, was an armed conflict that began in 1979 when the Khmer Rouge government of Democratic Kampuchea was deposed during the Cambodian-Vietnamese War. The war concluded in 1999 when remaining Khmer Rouge forces surrendered. Between 1979 and the 1991 Paris Peace Agreements, it was fought between the Vietnam-supported People's Republic of Kampuchea and an opposing coalition. After 1991, the unrecognized Khmer Rouge government and insurgent forces continued to fight against the new government of Cambodia from remote areas until their defeat in 1999.