The Göta älv is a river that drains lake Vänern into the Kattegat, at the city of Gothenburg, on the western coast of Sweden. It was formed at the end of the last glaciation, as an outflow channel from the Baltic Ice Lake to the Atlantic Ocean and nowadays it has the largest drainage basin in Scandinavia.

Vänern is the largest lake in Sweden, the largest lake in the European Union and the third-largest lake in Europe after Ladoga and Onega in Russia. It is located in the provinces of Västergötland, Dalsland, and Värmland in the southwest of the country. With its surface located at 44 metres (144 ft) with a maximum depth of 106 metres (348 ft), the lowest point of the Vänern basin is at 62 metres (203 ft) below sea level. The average depth is at a more modest 28 metres (92 ft), which means that the average point of the lake floor remains above sea level.

Forshaga Municipality is a municipality in Värmland County in west central Sweden. Its seat is located in the town of Forshaga.

Hammarö Municipality is a municipality in Värmland County in west central Sweden. Its seat is located in the town of Skoghall.

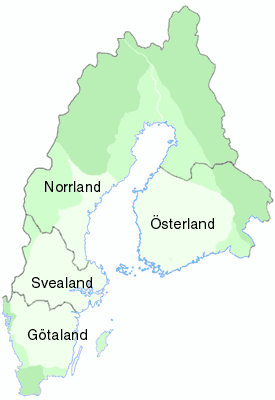

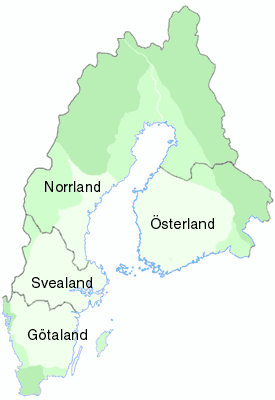

The Geats, sometimes called Goths, were a large North Germanic tribe who inhabited Götaland in modern southern Sweden from antiquity until the Late Middle Ages. They are one of the progenitor groups of modern Swedes, along with Swedes and Gutes. The name of the Geats also lives on in the Swedish provinces of Västergötland and Östergötland, the western and eastern lands of the Geats, and in many other toponyms.

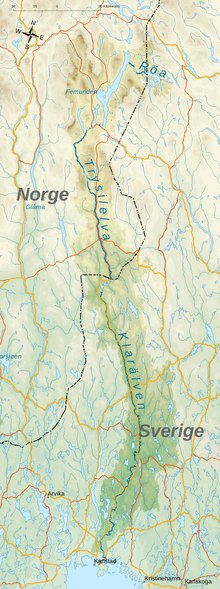

Dalsland is a Swedish traditional province, or landskap, situated in Götaland in southern Sweden. Lying to the west of Lake Vänern, it is bordered by Värmland to the north, Västergötland to the southeast, Bohuslän to the west, and Norway to the northwest.

Värmland is a landskap in west-central Sweden. It borders Västergötland, Dalsland, Dalarna, Västmanland, and Närke, and is bounded by Norway in the west.

Svealand, or Swealand, is the historical core region of Sweden. It is located in south central Sweden and is one of three historical lands of Sweden, bounded to the north by Norrland and to the south by Götaland. Deep forests, Tiveden, Tylöskog, and Kolmården, separated Svealand from Götaland. Historically, its inhabitants were called Svear, from which is derived the English 'Swedes'.

The Ume River is one of the main rivers in northern Sweden. It is around 460 km (290 mi) long, and flows in a south-eastern direction from its source, the lake Överuman by the Norwegian border within the Scandinavian mountain range. For large parts, the European route E12, also known as Blå Vägen, follows its path.

Söderåsen is a northwest–southwest elongated bedrock ridge in Scania in southern Sweden. On Söderåsen is Scania's highest point at 212 m (696 ft) above sea level. It is intersected by several fissure valleys. The ridge extends from Röstånga in the southeast to the Åstorp in northwest.

Eric Anundsson or Eymundsson was a semi-legendary Swedish king who supposedly ruled during the 9th century. The Norse sagas describe him as successful in extending his realm over the Baltic Sea, but unsuccessful in his attempts of westward expansion. There is no near-contemporary evidence for his existence, the sources for his reign dating from the 13th and 14th centuries. These sources, Icelandic sagas, are generally not considered reliable sources for the periods and events they describe.

Karlstad is the 20th-largest city in Sweden, the seat of Karlstad Municipality, the capital of Värmland County, and the largest city in the province Värmland in Sweden. The city proper had 67,122 inhabitants in 2020 with 97,233 inhabitants in the wider municipality in 2023, and is the 21st biggest municipality in Sweden. Karlstad has a university and a cathedral.

Trollhättan is the 23rd-largest city in Sweden, the seat of Trollhättan Municipality, Västra Götaland County. It is situated by Göta älv, near the lake Vänern, and has a population of approximately 50,000 in the city proper. It is located 75 km (46 mi) north of Sweden's second-largest city, Gothenburg.

Sommen is a lake in the South Swedish highlands lying across the border of the provinces of Östergötland and Småland. Situated about 147 metres above mean sea level, the lake has an area of 132 km2 (51 sq mi) and has a maximum depth of 60 metres. The lake is shared between the administrative kommunes of Ydre, Kinda, Boxholm and Tranås and the area around it is sparsely populated.

Ancylus Lake is a name given by geologists to a large freshwater lake that existed in northern Europe approximately from 9500 to 8000 years BC being in effect one of various predecessors to the modern Baltic Sea.

The Weichselian glaciation was the last glacial period and its associated glaciation in northern parts of Europe. In the Alpine region it corresponds to the Würm glaciation. It was characterized by a large ice sheet that spread out from the Scandinavian Mountains and extended as far as the east coast of Schleswig-Holstein, northern Poland and Northwest Russia. This glaciation is also known as the Weichselian ice age, Vistulian glaciation, Weichsel or, less commonly, the Weichsel glaciation, Weichselian cold period (Weichsel-Kaltzeit), Weichselian glacial (Weichsel-Glazial), Weichselian Stage or, rarely, the Weichselian complex (Weichsel-Komplex).

Vättern is the second largest lake by surface area in Sweden, after Vänern, and the sixth largest lake in Europe. It is a long, finger-shaped body of fresh water in south central Sweden, to the southeast of Vänern, pointing at the tip of Scandinavia. Being a deep lake at 128 metres (420 ft) below sea level at its deepest point, Vättern is about 1/3 the surface area of Vänern but in spite of this contains roughly 1/2 of its water.

A blockfield, felsenmeer, boulder field or stone field is a surface covered by boulder- or block-sized rocks usually associated with a history of volcanic activity, alpine and subpolar climates and periglaciation. Blockfields differ from screes and talus slope in that blockfields do not apparently originate from mass wastings. They are believed to be formed by frost weathering below the surface. An alternative theory that modern blockfields may have originated from chemical weathering that occurred in the Neogene when the climate was relatively warmer. Following this thought the blockfields would then have been reworked by periglacial action.

Höljes Hydroelectric Power Station is a hydroelectric power plant on the Klarälven in Torsby Municipality, Värmland County, Sweden.

Åke Sundborg was a Swedish geographer and geomorphologist known for his contributions to the hydrology and geomorphological dynamics of rivers. He was active at Uppsala University where he studied under the supervision of Filip Hjulström eventually succeeding him on the chair of physical geography. Besides his studies of rivers Sundborg made contributions on the climate of cities, the distribution of loess and the sedimentation of reservoirs and lakes. He studied rivers in Sweden as well as various large rivers in Africa and Asia.