History

Origins

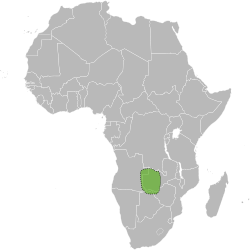

The Kololo are said to have been displaced by the Zulu expansion under Shaka in the early 19th century during a chain of events known as the Mfecane. In 1823, the Kololo started a migration north through Botswana to Barotseland. [4] In what is now southern Botswana, they defeated a number of societies before suffering a catastrophic defeat to the Bangwaketse at Dithubaruba in 1826. [5] After losing all their cattle they moved north east and raided again, but subsequent defeats led them north to Okavango Delta where they again suffered major losses but were able to defeat the Batawana people in 1835. This victory enabled them to replenish their population and cattle holdings, although they moved north after several years. [6]

Sebetwane dynasty in Barotseland

At some point in the late 1820s or in the 1830s, a group of Makololo led Sebetwane, which had migrated in a series of steps from their home area close to Basutoland, crossed the Zambezi River at Kazungula. After plundering the Batoka plateau, Sebetwane's group was driven west by the Matabele from the south and the Mashukulumbe or Ila people from the north. In the Bulozi floodplain, they encountered Lozi people from the Kingdom of Barotseland, who at the time had been seriously weakened by a war of succession following the death of king Mulambwa Santulu between his sons Silumelume and Mubukwanu. By 1845, Sebetwane had conquered Barotseland and became king. He died in 1851 shortly after meeting David Livingstone, and was succeeded, first, by his daughter Mamochisane, who soon abdicated in favour of her younger half-brother Sekeletu. [10]

After about 20 years, the Makololo dynasty of Sebetwane in Barotseland came to an end in 1864. This was the result of the Makololo war of succession (1863–1864), which broke out after the death of morêna Sekeletu of Barotseland, between Mamili/Mamile (Sekeletu's confidant and close associate) and Mbololo/Mpololo (Sekeletu's uncle, Sebetwane's brother). The war ended when the northern Lukwakwa faction led by Njekwa captured the Makololo faction's strongholds in the south, allegedly putting to death all potential 'pure Makololo' claimants to the throne, and inviting Sipopa Lutangu (Mubukwanu's son, Mulambwa's grandson) to become the new king. Conventional historiography regards the 1864 accession of Sipopa Lutangu as "the 'Restoration' of the Lozi monarchy and the start of the 'Second Kingdom'", but Flint (2005) argued that the Lozi and Makololo peoples were ethnolinguistically close and had 'effectively merged' in the decades following the accession of Sebetwane, demonstrated by the fact that both groups spoke the 'Sikololo' or 'Silozi' language by 1864. Sipopa was 'on good terms with the Makololo hierarchy' and married Sebetwane's daughter Mamochisane upon his accession. There are claims that all Makololo men were killed and only Makololo women and children survived, [17] but there is evidence of Makololo men living in Barotseland after 1864, so Flint (2005) concluded that this assertion is a 'lie'. Moreover, after decades of intermarriage and cultural blending between two groups who were already very closely related, it would have been virtually impossible 'to weed out who was Makololo and who was not'.

Visit of David Livingstone

Sekeletu provided British explorer David Livingstone with many porters for his transcontinental journey from Luanda on the Atlantic to Quelimane on the Indian Ocean, made between 1854 and 1856. Around 100 of these men were left at Tete in 1856 when Livingstone made his way to Quelimane and then to Britain. [18] Livingstone returned to Africa to start his second Zambezi expedition in 1858. On reaching Tete, he was reunited with the porters he left there in 1856 and attempted to repatriate them all to Barotseland. However, by this time Sekeletu was facing increasing opposition from the Lozi majority, and around 16 of them decided to remain on the middle Zambezi. [19]

Those Makololo remaining were used from 1859 onward, by Livingstone and by missionaries of the Universities' Mission to Central Africa (UMCA), as porters and armed guards to support their activities in the Shire valley and Shire Highlands including the freeing of slaves, and were paid in guns, ammunition and cloth. The Makololo decided to remain in the Shire valley when the missionaries left in January 1864. [20]

After the 1864 departure of the UMCA mission, which left behind supplies of arms and ammunition, the Makololo maintained themselves by hunting elephants for ivory and attracted dependents seeking protection, many of whom were freed slaves. They and their armed dependents established chieftaincies in the present-day Chikwawa District. Originally, ten Makololo became chiefs or headmen and five Makololo chiefs still exist today. [21]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.