Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segregated schools are otherwise equal in quality. Handed down on May 17, 1954, the Court's unanimous (9–0) decision stated that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal", and therefore violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. However, the decision's 14 pages did not spell out any sort of method for ending racial segregation in schools, and the Court's second decision in Brown II only ordered states to desegregate "with all deliberate speed".

Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000), was a decision of the United States Supreme Court on December 12, 2000, that settled a recount dispute in Florida's 2000 presidential election between George W. Bush and Al Gore.

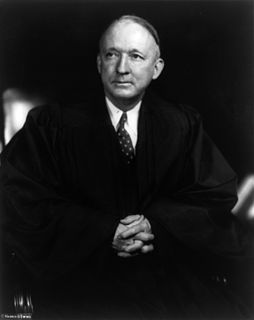

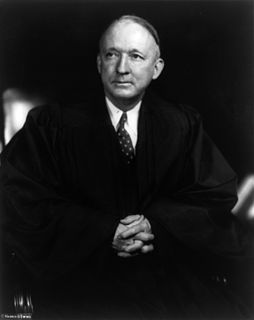

Hugo Lafayette Black was an American lawyer, politician, and jurist who served as a U.S. Senator from 1927 to 1937 and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1937 to 1971. A member of the Democratic Party and a devoted New Dealer, Black endorsed Franklin D. Roosevelt in both the 1932 and 1936 presidential elections. Having gained a reputation in the Senate as a reformer, Black was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Roosevelt and confirmed by the Senate by a vote of 63 to 16. He was the first of nine Roosevelt appointees to the Court, and he outlasted all except for William O. Douglas.

Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971), was a case argued before the Supreme Court of the United States. The court ruled in an 8–1 decision that Pennsylvania's Nonpublic Elementary and Secondary Education Act from 1968 was unconstitutional, violating the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. The act allowed the Superintendent of Public Schools to reimburse private schools for the salaries of teachers who taught in these private elementary schools from public textbooks and with public instructional materials.

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a landmark civil rights decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that laws banning interracial marriage violate the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Beginning in 2013, it was cited as precedent in U.S. federal court decisions holding restrictions on same-sex marriage in the United States unconstitutional, including in the 2015 Supreme Court decision Obergefell v. Hodges.

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954), is a landmark United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that the Constitution prohibits segregated public schools in the District of Columbia. Originally argued on December 10–11, 1952, a year before Brown v. Board of Education, Bolling was reargued on December 8–9, 1953, and was unanimously decided on May 17, 1954, the same day as Brown. The Bolling decision was supplemented in 1955 with the second Brown opinion, which ordered desegregation "with all deliberate speed". In Bolling, the Court did not address school desegregation in the context of the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause, which applies only to the states, but rather held that school segregation was unconstitutional under the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Court observed that the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution lacked an Equal Protection Clause, as in the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Court held, however, that the concepts of Equal Protection and Due Process are not mutually exclusive, establishing the reverse incorporation doctrine.

John Marshall Harlan was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. Harlan is usually called John Marshall Harlan II to distinguish him from his grandfather John Marshall Harlan, who served on the Supreme Court from 1877 to 1911.

The Equal Protection Clause is part of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The clause, which took effect in 1868, provides "nor shall any State ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws". It mandates that individuals in similar situations be treated equally by the law.

Golan v. Holder, 565 U.S. 302 (2012), was a Supreme Court case that dealt with copyright and the public domain. It held that the "limited time" language of the United States Constitution's Copyright Clause does not preclude the extension of copyright protections to works previously in the public domain.

Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (1956), was a case heard before a three-judge panel of the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama on Montgomery and Alabama state bus segregation laws. The panel consisted of Middle District of Alabama Judge Frank Minis Johnson, Northern District of Alabama Judge Seybourn Harris Lynne, and Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Richard Rives. The main plaintiffs in the case were Aurelia Browder, Claudette Colvin, Susie McDonald, and Mary Louise Smith. Jeanetta Reese had originally been a plaintiff in the case, but intimidation by segregationists caused her to withdraw in February. She falsely claimed she had not agreed to the lawsuit, which led to an unsuccessful attempt to disbar Fred Gray for supposedly improperly representing her.

Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253 (1967), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, which ruled that citizens of the United States may not be deprived of their citizenship involuntarily. The U.S. government had attempted to revoke the citizenship of Beys Afroyim, a man born in Poland, because he had cast a vote in an Israeli election after becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen. The Supreme Court decided that Afroyim's right to retain his citizenship was guaranteed by the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. In so doing, the Court struck down a federal law mandating loss of U.S. citizenship for voting in a foreign election—thereby overruling one of its own precedents, Perez v. Brownell (1958), in which it had upheld loss of citizenship under similar circumstances less than a decade earlier.

Braunfeld v. Brown, 366 U.S. 599 (1961), was a case decided by the United States Supreme Court. In a 6-3 decision, the Court held that a Pennsylvania law forbidding the sale of various retail products on Sunday was not an unconstitutional interference with religion as described in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry, 548 U.S. 399 (2006), is a Supreme Court of the United States case in which the Court ruled that only District 23 of the 2003 Texas redistricting violated the Voting Rights Act. The Court refused to throw out the entire plan, ruling that the plaintiffs failed to state a sufficient claim of partisan gerrymandering.

In United States law, a federal enclave is a parcel of federal property within a state that is under the "Special Maritime and Territorial Jurisdiction of the United States". In 1960, the year of the latest comprehensive inquiry, 7% of federal property had enclave status. Of the land with federal enclave status, 57% was under "concurrent" state jurisdiction. The remaining 43%, on which some state laws do not apply, was scattered almost at random throughout the United States. In 1960, there were about 5,000 enclaves, with about one million people living on them. While a comprehensive inquiry has not been performed since 1960, these statistics are likely much lower today, since many federal enclaves were military bases that have been closed and transferred out of federal ownership.

William Hubbs Rehnquist was an American lawyer and jurist who served on the Supreme Court of the United States for 33 years, as an associate justice from 1972 to 1986 and as Chief Justice from 1986 until his death in 2005. Considered a conservative, Rehnquist favored a conception of federalism that emphasized the Tenth Amendment's reservation of powers to the states. Under this view of federalism, the court, for the first time since the 1930s, struck down an act of Congress as exceeding its power under the Commerce Clause.

Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23 (1968), was a case before the United States Supreme Court.

Citizens for Equal Protection v. Bruning, 455 F.3d 859, was a federal lawsuit filed in the United States District Court for the District of Nebraska and decided on appeal by the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. It challenged the federal constitutionality of Nebraska Initiative Measure 416, a 2000 ballot initiative that amended the Nebraska Constitution to prohibit the recognition of same-sex marriages, civil unions, and other same-sex relationships.

Board of Trustees of Scarsdale v. McCreary, 471 U.S. 83 (1985), was a United States Supreme Court case in which an evenly split Court upheld per curiam a lower court's decision that the display of a privately sponsored nativity scene on public property does not violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer, 582 U.S. ___ (2017), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that a Missouri program that denied a grant to a religious school for playground resurfacing, while providing grants to similarly situated non-religious groups, violated the freedom of religion guaranteed by the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Califano v. Goldfarb, 430 U.S. 199 (1977), was a decision by the United States Supreme Court, which held that the different treatment of men and women mandated by 42 U.S.C. § 402(f)(1)(D) constituted invidious discrimination against female wage earners by affording them less protection for their surviving spouses than is provided to male employees, and therefore violated the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The case was brought by a widower who was denied survivor benefits on the grounds that he had not been receiving at least one-half support from his wife when she died. Justice Brennan delivered the opinion of the court, ruling unconstitutional the provision of the Social Security Act which set forth a gender-based distinction between widows and widowers, whereby Social Security Act survivors benefits were payable to a widower only if he was receiving at least half of his support from his late wife, while such benefits based on the earnings of a deceased husband were payable to his widow regardless of dependency. The Court found that this distinction deprived female wage earners of the same protection that a similarly situated male worker would have received, violating due process and equal protection.