Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in Ghana face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Sexual acts between males have been illegal as "unnatural carnal knowledge" in Ghana since the colonial era. The majority of Ghana's population hold anti-LGBT sentiments. Physical and violent homophobic attacks against LGBT people occur, and are often encouraged by the media and religious and political leaders. At times, government officials, such as police, engage in such acts of violence. Young gay people are known to be disowned by their families and communities and evicted from their homes. Families often seek conversion therapy from religious groups when same-sex orientation or non-conforming gender identity is disclosed; such "therapy" is reported to be commonly administered in abusive and inhumane settings.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Afghan members of the LGBT community are forced to keep their gender identity and sexual orientation secret, in fear of violence and the death penalty. The religious nature of the country has limited any opportunity for public discussion, with any mention of homosexuality and related terms deemed taboo.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Egypt face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. There are reports of widespread discrimination and violence towards openly LGBT people within Egypt, with police frequently prosecuting gay and transgender individuals.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people in the United Arab Emirates face discrimination and legal challenges. Homosexuality is illegal in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and under the federal criminal provisions, consensual same-sex sexual activity is punishable by imprisonment; extra-marital sexual activity between persons of different sexes is also illegal. In both cases, prosecution will only be brought if a husband or male guardian of one of the participants makes a criminal complaint. The penalty is a minimum of six months imprisonment; no maximum penalty is prescribed, and the court has full discretion to impose any sentence in accordance with the country's constitution.

Joël Gustave Nana Ngongang (1982–2015), frequently known as Joel Nana, was a leading African LGBT human rights advocate and HIV/AIDS activist. Nana's career as a human rights advocate spanned numerous African countries, including Nigeria, Senegal and South Africa, in addition to his native Cameroon. He was the Chief Executive Officer of Partners for Rights and Development (Paridev) a boutique consulting firm on human rights, development and health in Africa at the time of his death. Prior to that position, he was the founding Executive Director of the African Men for Sexual Health and Rights (AMSHeR) an African thought and led coalition of LGBT/MSM organizations working to address the vulnerability of MSM to HIV. Mr Nana worked in various national and international organizations, including the Africa Research and Policy Associate at the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (IGLHRC), as a Fellow at Behind the Mask, a Johannesburg-based non-profit media organisation publishing a news website concerning gay and lesbian affairs in Africa, he wrote on numerous topics in the area of African LGBT and HIV/AIDS issues and was a frequent media commentator. Nana died on October 15, 2015, after a brief illness.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Ethiopia face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female types of same-sex sexual activity are illegal in the country, with reports of high levels of discrimination and abuses against LGBT people. Ethiopia has a long history of social conservatism and same-sex sexual activity is considered a cultural taboo.

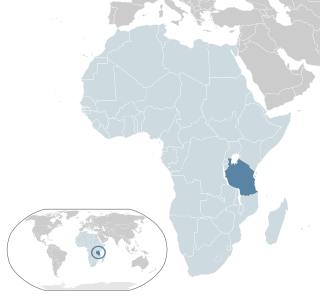

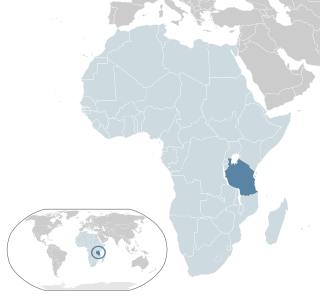

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Tanzania face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Homosexuality in Tanzania is a socially taboo topic, and same-sex sexual acts are criminal offences, punishable with life imprisonment. The law also criminalises heterosexuals who engage in oral sex and anal intercourse.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Botswana face legal issues not experienced by non-LGBTQ citizens. Both female and male same-sex sexual acts have been legal in Botswana since 11 June 2019 after a unanimous ruling by the High Court of Botswana. Despite an appeal by the government, the ruling was upheld by the Botswana Court of Appeal on 29 November 2021.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Burundi face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ citizens. While never criminalized before 2009, Burundi has since criminalized same-sex sexual activity by both men and women with a penalty up to two years in prison and a fine. LGBT persons are regularly prosecuted and persecuted by the government and additionally face stigmatisation among the broader population.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Sudan face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity in Sudan is illegal for both men and women, while homophobic attitudes remain ingrained throughout the nation.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Papua New Guinea face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Male same-sex sexual activity is illegal, punishable by up to 14 years' imprisonment. The law is rarely enforced, but arrests still do happen, having occurred in 2015 and 2022. There are no legal restrictions against lesbian sex in the country.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Uganda face severe legal and social challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is illegal for both men and women in Uganda. It was originally criminalised by British colonial laws introduced when Uganda became a British protectorate, and these laws have been retained since the country gained its independence.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Senegal experience legal persecution. Senegal specifically outlaws same-sex sexual acts and, in the past, has prosecuted men accused of homosexuality. Members of the LGBT community face routine discrimination in Senegalese society.

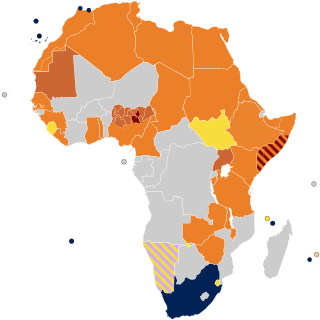

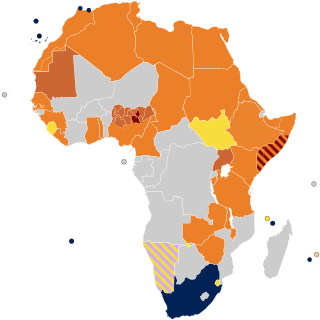

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Africa are generally poor in comparison to the Americas, Western Europe and Oceania.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Zambia face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is illegal for both men and women in Zambia. Formerly a colony of the British Empire, Zambia inherited the laws and legal system of its colonial occupiers upon independence in 1964. Laws concerning homosexuality have largely remained unchanged since then, and homosexuality is covered by sodomy laws that also proscribe bestiality. Social attitudes toward LGBT people are mostly negative and coloured by perceptions that homosexuality is immoral and a form of insanity. However, in recent years, younger generations are beginning to show positive and open minded attitudes towards their LGBT peers.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Sierra Leone face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Male same-sex sexual activity is illegal in Sierra Leone and carries a possible penalty of life imprisonment, although this law is seldom enforced.

Alice Nkom is a Cameroonian lawyer, well known for her advocacy towards decriminalization of homosexuality in Cameroon. She studied law in Toulouse and has been a lawyer in Douala since 1969. At the age of 24, she was the first black French-speaking woman called to the bar in Cameroon.

Jean-Claude Roger Mbede was a Cameroonian man who was sentenced to three years' imprisonment on charges of homosexuality and attempted homosexuality. His sentence was protested by international human rights organizations including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, the latter of which named him a prisoner of conscience.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people generally have limited or highly restrictive rights in most parts of the Middle East, and are open to hostility in others. Sex between men is illegal in 9 of the 18 countries that make up the region. It is punishable by death in four of these 18 countries. The rights and freedoms of LGBT citizens are strongly influenced by the prevailing cultural traditions and religious mores of people living in the region – particularly Islam.

The following outline offers an overview and guide to LGBTQ topics: