Related Research Articles

The LGBTQ community is a loosely defined grouping of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning individuals united by a common culture and social movements. These communities generally celebrate pride, diversity, individuality, and sexuality. LGBTQ activists and sociologists see LGBTQ community-building as a counterweight to heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, sexualism, and conformist pressures that exist in the larger society. The term pride or sometimes gay pride expresses the LGBTQ community's identity and collective strength; pride parades provide both a prime example of the use and a demonstration of the general meaning of the term. The LGBTQ community is diverse in political affiliation. Not all people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender consider themselves part of the LGBTQ community.

A gay–straight alliance, gender–sexuality alliance (GSA) or queer–straight alliance (QSA) is a student-led or community-based organization, found in middle schools, high schools, colleges, and universities. These are primarily in the United States and Canada. Gay–straight alliance is intended to provide a safe and supportive environment for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and all LGBTQ+ individuals, children, teenagers, and youth as well as their cisgender heterosexual allies. The first GSAs were established in the 1980s. Scientific studies show that GSAs have positive academic, health, and social impacts on schoolchildren of a minority sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Numerous judicial decisions in United States federal and state court jurisdictions have upheld the establishment of GSAs in schools, and the right to use that name for them.

LGBTQ culture is a culture shared by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer individuals. It is sometimes referred to as queer culture, LGBT culture, and LGBTQIA culture, while the term gay culture may be used to mean either "LGBT culture" or homosexual culture specifically.

The origin of the LGBT student movement can be linked to other activist movements from the mid-20th century in the United States. The Civil Rights Movement and Second-wave feminist movement were working towards equal rights for other minority groups in the United States. Though the student movement began a few years before the Stonewall riots, the riots helped to spur the student movement to take more action in the US. Despite this, the overall view of these gay liberation student organizations received minimal attention from contemporary LGBT historians. This oversight stems from the idea that the organizations were founded with haste as a result of the riots. Others historians argue that this group gives too much credit to groups that disagree with some of the basic principles of activist LGBT organizations.

Robyn Ochs is an American bisexual activist, professional speaker, and workshop leader. Her primary fields of interest are gender, sexuality, identity, and coalition building. She is the editor of the Bisexual Resource Guide, Bi Women Quarterly, and the anthology Getting Bi: Voices of Bisexuals Around the World. Ochs, along with Professor Herukhuti, co-edited the anthology Recognize: The Voices of Bisexual Men.

James Willis Toy was a long-time American activist and a pioneer for LGBT rights in Michigan.

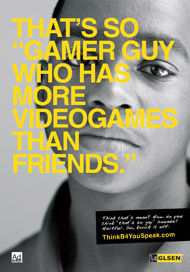

The Think Before You Speak campaign is a television, radio, and magazine advertising campaign launched in 2008 and developed to raise awareness of the common use of derogatory vocabulary among youth towards lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning (LGBTQ) people. It also aims to "raise awareness about the prevalence and consequences of anti-LGBTQ bias and behaviour in America's schools." As LGBTQ people have become more accepted in the mainstream culture, more studies have confirmed that they are one of the most targeted groups for harassment and bullying. An "analysis of 14 years of hate crime data" by the FBI found that gays and lesbians, or those perceived to be gay, "are far more likely to be victims of a violent hate crime than any other minority group in the United States". "As Americans become more accepting of LGBT people, the most extreme elements of the anti-gay movement are digging in their heels and continuing to defame gays and lesbians with falsehoods that grow more incendiary by the day," said Mark Potok, editor of the Intelligence Report. "The leaders of this movement may deny it, but it seems clear that their demonization of gays and lesbians plays a role in fomenting the violence, hatred and bullying we're seeing." Because of their sexual orientation or gender identity/expression, nearly half of LGBTQ students have been physically assaulted at school. The campaign takes positive steps to counteract hateful and anti-gay speech that LGBTQ students experience in their daily lives in hopes to de-escalate the cycle of hate speech/harassment/bullying/physical threats and violence.

Various issues in medicine relate to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people. According to the US Gay and Lesbian Medical Association (GLMA), besides HIV/AIDS, issues related to LGBT health include breast and cervical cancer, hepatitis, mental health, substance use disorders, alcohol use, tobacco use, depression, access to care for transgender persons, issues surrounding marriage and family recognition, conversion therapy, refusal clause legislation, and laws that are intended to "immunize health care professionals from liability for discriminating against persons of whom they disapprove."

Point Foundation is a scholarship fund that provides financial aid for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) college bound students in the United States. Founded in 2001, the overall mission of this organization to give these individuals the opportunity to receive the resources that they need to become pillars in society. It is one of only a few scholarship organizations that is solely for LGBTQ+ students.

Research has found that attempted suicide rates and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) youth are significantly higher than among the general population.

Campus Pride is an American national nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization founded by M. Chad Wilson, Sarah E. Holmes and Shane L. Windmeyer in 2001 which serves lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) and ally student leaders and/or campus organization in the areas of leadership development, support programs and services to create safer, more inclusive LGBT-friendly colleges and universities.

The Spectrum Center is an office at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor that is dedicated to providing education, outreach, and advocacy for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and allied (LGBTQA) community. Since the organizations' creation in 1971, the Spectrum Center's mission statement has been to "enrich the campus experience and develop students as individuals and as members of the LGBTQA community." The organization achieves this through student-centered education, outreach, advocacy and support.

Historically speaking, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people have not been given equal treatment and rights by both governmental actions and society's general opinion. Much of the intolerance for LGBT individuals come from lack of education around the LGBT community, and contributes to the stigma that results in same-sex marriage being legal in few countries (31) and persistence of discrimination, such as in the workplace.

Ronni Lebman Sanlo is the Director Emeritus of the UCLA Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Center and an authority on matters relating to LGBT students, faculty and staff in higher education. She recognized at an early age that she was a lesbian, but was too afraid to tell anybody. Sanlo went to college then married and had two children. At the age of 31, Ronni came out and lost custody of her young children. The treatment toward the LBGT community and her rights as a mother are what gave Sanlo the drive to get involved in activism and LGBT politics.

The following outline offers an overview and guide to LGBTQ topics:

Homosocialization or LGBT socialization is the process by which LGBTQ people meet, relate and become integrated in the LGBT community, especially with people of the same sexual orientation and gender identity, helping to build their own identity as well.

LGBTQ psychology is a field of psychology of surrounding the lives of LGBTQ+ individuals, in the particular the diverse range of psychological perspectives and experiences of these individuals. It covers different aspects such as identity development including the coming out process, parenting and family practices and support for LGBTQ+ individuals, as well as issues of prejudice and discrimination involving the LGBTQ community.

Due to the increased vulnerability that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth face compared to their non-LGBT peers, there are notable differences in the mental and physical health risks tied to the social interactions of LGBT youth compared to the social interactions of heterosexual youth. Youth of the LGBT community experience greater encounters with not only health risks, but also violence and bullying, due to their sexual orientation, self-identification, and lack of support from institutions in society.

Susan Ruth Rankin is an American academic specializing in higher education policy and queer studies. She was a member of the faculty and administration at Pennsylvania State University from 1979 to 2013. Rankin is recognized as a prominent figure in the LGBTQ sports movement and was one of the first openly lesbian NCAA Division I coaches.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Fine, Leigh E. (2012). "The Context of Creating Space: Assessing the Likelihood of College LGBT Center Presence". Journal of College Student Development. 53 (2): 285–299. doi:10.1353/csd.2012.0017. S2CID 145572701.

- 1 2 3 Luthra, Aman (2004). "(Un)Straightening the Syracuse University Landscape". In Farrell, Kathleen; Gupta, Nisha; Queen, Mary (eds.). Interrupting Heteronormativity: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Pedagogy and Responsible Teaching at Syracuse University. pp. 45–53.

- ↑ "Bowie State Boasts First Black LGBT Student Center". Tell Me More. NPR. 14 June 2012. ProQuest 1020394942.

- ↑ McCabe, Paul C.; Rubinson, Florence (1 December 2008). "Committing to Social Justice: The Behavioral Intention of School Psychology and Education Trainees to Advocate for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered Youth". School Psychology Review. 37 (4): 469–486. doi:10.1080/02796015.2008.12087861. S2CID 142657723.

- 1 2 Garvey, Jason C.; Sanders, Laura A.; Flint, Maureen A. (2017). "Generational Perceptions of Campus Climate Among LGBTQ Undergraduates". Journal of College Student Development. 58 (6): 795–817. doi:10.1353/csd.2017.0065. S2CID 149234337.

- ↑ "LGBT Map". www.lgbtcampus.org. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- 1 2 3 Ecker, John; Rae, Jennifer; Bassi, Amandeep (November 2015). "Showing your pride: a national survey of queer student centres in Canadian colleges and universities". Higher Education. 70 (5): 881–898. doi:10.1007/s10734-015-9874-x. S2CID 144986894.

- ↑ "ALOK named first Scholar in Residence at Penn's Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Center". 6 March 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sokolowski, Elizabeth (31 December 2017). Resource utilization of an LGBT university resource center and prospective barriers (Thesis). hdl:10217/191394.

- 1 2 3 Consortium of Higher Education LGBT Resource Professionals. (2017). [Interactive Map of LGBTQ Campus Resource Centers May 8, 2017]. Find an LGBTQ Resource Center. Retrieved from http://www.lgbtcampus.org/find-a-lgbt-center .

- ↑ Renn, Kirsten A. (2011). "Identity centers: An idea whose time has come...and gone?". In Magolda, Peter M.; Magolda, Marcia B. Baxter (eds.). Contested Issues in Student Affairs: Diverse Perspectives and Respectful Dialogue. Stylus. pp. 244–254. ISBN 978-1-57922-584-1.

- ↑ Gortmaker, V.; Brown, R. (2006). "Out of the closet: Differences in perceptions and experiences among out lesbian and gay students". College Student Journal. 40: 606–619.

- ↑ Garvey, Jason C.; Rankin, Susan R. (4 March 2015). "The Influence of Campus Experiences on the Level of Outness Among Trans-Spectrum and Queer-Spectrum Students". Journal of Homosexuality. 62 (3): 374–393. doi:10.1080/00918369.2014.977113. PMID 25321425. S2CID 5851202.

- ↑ "SDA - GSS 1972-2016 Cumulative Datafile". sda.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- ↑ Vaccaro, Annemarie (October 2012). "Campus Microclimates for LGBT Faculty, Staff, and Students: An Exploration of the Intersections of Social Identity and Campus Roles". Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. 49 (4): 429–446. doi:10.1515/jsarp-2012-6473. S2CID 145703210.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pitcher, Erich N.; Camacho, Trace P.; Renn, Kristen A.; Woodford, Michael R. (June 2018). "Affirming policies, programs, and supportive services: Using an organizational perspective to understand LGBTQ+ college student success". Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. 11 (2): 117–132. doi:10.1037/dhe0000048. S2CID 151842411.

- 1 2 3 Rankin, Susan; Reason, Robert (December 2008). "Transformational Tapestry Model: A comprehensive approach to transforming campus climate" (PDF). Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. 1 (4): 262–274. doi:10.1037/a0014018. S2CID 28591832. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-22.

- ↑ BrckaLorenz, Allison; Garvey, Jason C.; Hurtado, Sarah S.; Latopolski, Keely (December 2017). "High-impact practices and student–faculty interactions for gender-variant students". Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. 10 (4): 350–365. doi:10.1037/dhe0000065. hdl: 2022/24053 . S2CID 148714341.

- ↑ Serving diverse students in Canadian higher education. Cox, Donna Gail Hardy, 1961-, Strange, Charles Carney. Montreal. June 2016. ISBN 978-0-7735-9942-0. OCLC 945583325.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - 1 2 Garvey, Jason C.; Rankin, Susan R. (3 April 2015). "Making the Grade? Classroom Climate for LGBTQ Students Across Gender Conformity". Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. 52 (2): 190–203. doi:10.1080/19496591.2015.1019764. S2CID 142627394.

- 1 2 Westbrook, Laurel (9 October 2009). "Where the Women Aren't: Gender Differences in the Use of LGBT Resources on College Campuses". Journal of LGBT Youth. 6 (4): 369–394. doi:10.1080/19361650903295769. S2CID 144571103.

- ↑ Poynter, Kerry John; Washington, Jamie (2005). "Multiple identities: Creating community on campus for LGBT students". New Directions for Student Services. 2005 (111): 41–47. doi:10.1002/ss.172. S2CID 143745822.

- ↑ Rankin, Susan R. (2005). "Campus climates for sexual minorities". New Directions for Student Services. 2005 (111): 17–23. doi:10.1002/ss.170.

- ↑ Martin, Georgianna; Broadhurst, Christopher; Hoffshire, Michael; Takewell, William (2 January 2018). "'Students at the Margins': Student Affairs Administrators Creating Inclusive Campuses for LGBTQ Students in the South". Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. 55 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/19496591.2017.1345756. S2CID 158276420.

- ↑ "Elon named a top-10 LGBTQ-friendly campus". Elon University. 19 August 2016.

- ↑ Garvey, Jason C.; Rankin, Susan; Beemyn, Genny; Windmeyer, Shane (September 2017). "Improving the Campus Climate for LGBTQ Students Using the Campus Pride Index: Improving the Campus Climate for LGBTQ Students". New Directions for Student Services. 2017 (159): 61–70. doi:10.1002/ss.20227.

- ↑ Garvey, J. C.; Drezner, N. D. (2013). "Alumni giving in the LGBTQ communities". In Drezner, N. D. (ed.). Expanding the donor base: Critical issues for higher education philanthropy and fundraising. New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 74–86.

- ↑ "LGBTQ+ Programs". Bowling Green State University. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- ↑ Rankin, S. R., Weber, G., Blumenfeld, W., & Frazer, S. (2010). State of higher education for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people. Charlotte, NC: Campus Pride.

- ↑ "UVM Prism Center". www.uvm.edu. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- ↑ "Pride Center". Pride Center. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- ↑ Gervin, C.W. (2016, Jun 26). UTK reinstates funding for LGBT center. Nashville Post. Retrieved from https://www.nashvillepost.com/politics/state-government/article/20865830/utk-reinstates-funding-for-lgbt-center

- ↑ Boykin, K. (2005). Beyond the Down Low: Sex, lies, and denial in black America. New York: Carral and Graf.[ page needed ]