Related Research Articles

Elam was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretching from the lowlands of what is now Khuzestan and Ilam Province as well as a small part of southern Iraq. The modern name Elam stems from the Sumerian transliteration elam(a), along with the later Akkadian elamtu, and the Elamite haltamti. Elamite states were among the leading political forces of the Ancient Near East. In classical literature, Elam was also known as Susiana, a name derived from its capital Susa.

Shala (Šala) was a Mesopotamian goddess of weather and grain and the wife of the weather god Adad. It is assumed that she originated in northern Mesopotamia and that her name might have Hurrian origin. She was worshiped especially in Karkar and in Zabban, regarded as cult centers of her husband as well. She is first attested in the Old Babylonian period, but it is possible that an analogous Sumerian goddess, Medimsha, was already the wife of Adad's counterpart Ishkur in earlier times.

Ruhurater or Lahuratil was an Elamite deity.

Humban was an Elamite god. He is already attested in the earliest sources preserving information about Elamite religion, but seemingly only grew in importance in the neo-Elamite period, in which many kings had theophoric names invoking him. He was connected with the concept of kitin, or divine protection.

Pinikir, also known as Pinigir, Pirengir, Pirinkir, and Parakaras, was an Ancient Near Eastern astral goddess who originates in Elamite religious beliefs. While she is only infrequently attested in Elamite documents, she achieved a degree of prominence in Hurrian religion. Due to her presence in pantheons of many parts of the Ancient Near East, from Anatolia to Iran, modern researchers refer to her as a "cosmopolitan deity."

Nahhunte was the Elamite sun god. While the evidence for the existence of temples dedicated to him and regular offerings is sparse, he is commonly attested in theophoric names, including these of members of Elamite royal families.

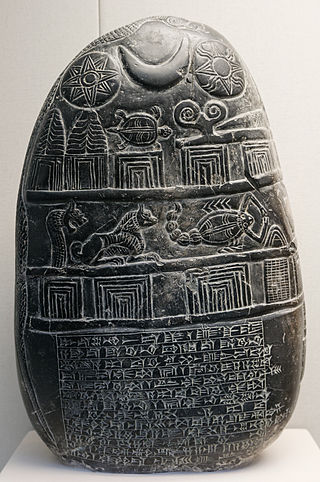

Inshushinak was the tutelary god of the city of Susa in Elam. His name has a Sumerian etymology, and can be translated as "lord of Susa". He was associated with kingship, and as a result appears in the names and epithets of multiple Elamite rulers. In Susa he was the main god of the local pantheon, though his status in other parts of Elam might have been different. He was also connected with justice and the underworld. His iconography is uncertain, though it is possible snakes were his symbolic animals. Two Mesopotamian deities incorporated into Elamite tradition, Lagamal and Ishmekarab, were regarded as his assistants. He was chiefly worshiped in Susa, where multiple temples dedicated to him existed. Attestations from other Elamite cities are less common. He is also attested in Mesopotamian sources, where he could be recognized as an underworld deity or as an equivalent of Ninurta. He plays a role in the so-called Susa Funerary Texts, which despite being found in Susa were written in Akkadian and might contain instructions for the dead arriving in the underworld.

Ištaran was a Mesopotamian god who was the tutelary deity of the city of Der, a city-state located east of the Tigris, in the proximity of the borders of Elam. It is known that he was a divine judge, and his position in the Mesopotamian pantheon was most likely high, but much about his character remains uncertain. He was associated with snakes, especially with the snake god Nirah, and it is possible that he could be depicted in a partially or fully serpentine form himself. He is first attested in the Early Dynastic period in royal inscriptions and theophoric names. He appears in sources from the reign of many later dynasties as well. When Der attained independence after the Ur III period, local rulers were considered representatives of Ištaran. In later times, he retained his position in Der, and multiple times his statue was carried away by Assyrians to secure the loyalty of the population of the city.

Ninegal or Belat Ekalli (Belet-ekalli) was a Mesopotamian goddess associated with palaces. Both her Sumerian and Akkadian name mean "lady of the palace."

Kiririsha was a major goddess worshiped in Elam.

Inzak was the main god of the pantheon of Dilmun. The precise origin of his name remains a matter of scholarly debate. He might have been associated with date palms. His cult center was Agarum, and he is invoked as the god of this location in inscriptions of Dilmunite kings. His spouse was the goddess Meskilak. A further deity who might have fulfilled this role was dPA.NI.PA, known from texts from Failaka Island.

Napirisha was a major Elamite deity. He likely originated from Anshan.

Narundi or Narunde was an Elamite goddess worshiped in Susa. She is attested there roughly between 2250 BCE and 1800 BCE. Multiple inscriptions mention her, and it assumed she was a popular deity at the time. In later periods, she occurs exclusively in Mesopotamia, where she played a role in apotropaic rituals in association with the Sebitti. Many attestations are available from late Assyrian sources, but it is not certain if they should be regarded as an indication of continuous worship.

Manzat (Manzât), also spelled Mazzi'at, Manzi'at and Mazzêt, sometimes known by the Sumerian name Tiranna (dTIR.AN.NA) was a Mesopotamian and Elamite goddess representing the rainbow. She was also believed to be responsible for the prosperity of cities.

Simut or Šimut (Shimut) was an Elamite god. He was regarded as the herald of the gods, and was associated with the planet Mars. He was closely associated with Manzat, a goddess representing the rainbow. He appears in inscriptions of various Elamite kings which mention a number of temples dedicated to him. However, it is not known which city served as his main cult center. He was also worshiped in Mesopotamia, where he was compared with the war god Nergal.

Urash (Uraš) was a Mesopotamian god who was the tutelary deity of Dilbat. He was an agricultural god, and in that capacity he was frequently associated with Ninurta. His wife was the goddess Ninegal, while his children were the underworld deity Lagamal, who like him was associated with Dilbat, and the love goddess Nanaya.

Ishmekarab (Išmekarab) or Ishnikarab (Išnikarab) was a Mesopotamian deity of justice. The name is commonly translated from Akkadian as "he heard the prayer," but Ishmekarab's gender is uncertain and opinions of researchers on whether the deity was male or female vary.

Idlurugu or Id (dÍD) was a Mesopotamian god regarded as both a river deity and a divine judge. He was the personification of a type of trial by ordeal, which shared its name with him.

Kittum, also known as Niĝgina, was a Mesopotamian goddess who was regarded as the embodiment of truth. She belonged to the circle of the sun god Utu/Shamash and was associated with law and justice.

Ikšudum or Yakšudum was a Mesopotamian god worshiped in the kingdom of Mari, possibly a deified ancestor. He was closely associated with Lagamal. A possibly related deity is also listed among the hounds of Marduk in the god list An = Anum. Texts from Mari mention a ritual procession of Ikšudum and Lagamal. The pair was also invoked in oath formulas.

References

- ↑ van der Toorn 1995, p. 368.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Marchesi & Marchetti 2019, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lambert 1983, p. 418.

- ↑ Lambert 1987a, p. 163.

- 1 2 Becking 1999, p. 498.

- ↑ George, Taniguchi & Geller 2010, p. 128.

- 1 2 George, Taniguchi & Geller 2010, p. 134.

- ↑ George, Taniguchi & Geller 2010, p. 123.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lambert 1983, p. 419.

- ↑ Lambert 1987, p. 152.

- 1 2 3 Henkelman 2008, p. 330.

- ↑ Henkelman 2008, p. 61.

- ↑ Krebernik 2016, p. 351.

- ↑ Sasson 2001, p. 413.

- 1 2 Durand 2000, p. 137.

- 1 2 Sasson 2015, p. 216.

- 1 2 3 Guichard 2019, p. 30.

- ↑ Guichard 2014, p. 46.

- 1 2 Jahangirfar 2018, p. 109.

- ↑ König 1965, p. 84.

- ↑ Lambert & Winters 2023, p. 338.

- ↑ Behrens & Klein 1998, p. 346.

- ↑ Wiggermann 1997, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 Wasserman 2019, p. 876.

- ↑ Nakata 1975, p. 23.

- ↑ Lambert 2016, pp. 71–72.

- 1 2 Lambert 1980, p. 45.

- 1 2 Guichard 2019, p. 54.

- ↑ Charpin 2011, p. 49.

- ↑ Guichard 2014, p. 127.

- ↑ Guichard 2019, p. 28.

- ↑ Guichard 2014, p. 128.

- ↑ Marchesi & Marchetti 2019, pp. 5–6.

- 1 2 3 Marchesi & Marchetti 2019, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 Matthews 1978, p. 155.

- 1 2 Feliu 2003, p. 123.

- ↑ Cohen 1993, p. 294.

- ↑ Sasson 2015, p. 255.

- ↑ Sasson 2015, p. 268.

- ↑ Feliu 2003, p. 116.

- ↑ Sasson 2015, pp. 254–255.

- ↑ Marchesi & Marchetti 2019, p. 9.

- ↑ Marchesi & Marchetti 2019, p. 4.

- ↑ Harris 1976, p. 152.

- 1 2 George 1992, p. 187.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 105.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 145.

- ↑ George 1992, p. 185.

- ↑ Henkelman 2008, p. 313.

- 1 2 Álvarez-Mon 2015, p. 19.

- ↑ Henkelman 2008, p. 443.

- ↑ Henkelman 2008, p. 442.

- 1 2 Potts 2010, p. 58.

- ↑ Henkelman 2008, p. 444.

- ↑ Potts 1999, p. 238.

- ↑ Potts 2010, p. 503.

- ↑ Potts 2010, p. 501.

- 1 2 Becking 1999, p. 499.

- ↑ Mofidi-Nasrabadi 2021, p. 5.

- ↑ Malbran-Labat 2018, pp. 470–471.

- ↑ Potts 1999, p. 255.

- ↑ Wasserman 2019, pp. 875–876.

- 1 2 Potts 2018, p. 12.

Bibliography

- Álvarez-Mon, Javier (2015). "Like a Thunderstorm: Storm-gods 'Sibitti' wWrriors from Highland Elam". AION: Annali dell'Università degli Studi di Napoli "L'Orientale". 74 (1–4): 17–46. ISSN 0393-3180 . Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- Behrens, Herman; Klein, Jacob (1998), "Ninegalla", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 2021-08-12

- Becking, Bob (1999), "Lagamar", in van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; van der Horst, Pieter W. (eds.), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, Eerdmans Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-8028-2491-2 , retrieved 2022-08-13

- Charpin, Dominique (2011). "Le « Pays De Mari Et Des Bédouins » À L'époque De Samsu-Iluna De Babylone". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 105: 41–59. ISSN 0373-6032.

- Cohen, Mark E. (1993). The Cultic Calendars of the Ancient Near East. Bethesda, Md.: CDL Press. ISBN 1-883053-00-5. OCLC 27431674.

- Durand, Jean-Marie (2000). Les documents épistolaires du palais de Mari. Tome III (in French). Cerf. ISBN 978-2204066167.

- Feliu, Lluís (2003). The god Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. Leiden Boston, MA: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-13158-3. OCLC 52107444 . Retrieved 2022-08-10.

- George, Andrew R. (1992). Babylonian Topographical Texts. Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta. Departement Oriëntalistiek. ISBN 978-90-6831-410-6 . Retrieved 2023-06-01.

- George, Andrew R. (1993). House most high: the temples of ancient Mesopotamia. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-80-3. OCLC 27813103.

- George, Andrew R.; Taniguchi, Junko; Geller, M. J. (2010). "The Dogs of Ninkilim, part two: Babylonian rituals to counter field pests". Iraq. 72. Cambridge University Press: 79–148. doi:10.1017/s0021088900000607. ISSN 0021-0889. S2CID 190713244.

- Guichard, Michaël (2014). L’épopée de Zimrī-Lîm. Floreglium Marianum. Vol. 14. Société pour l'étude du Proche-Orient Ancien.

- Guichard, Michaël (January 2019). "" Les statues divines et royales à Mari d'après les textes "". Journal Asiatique. 397 (1): 1–57. doi:10.2143/JA.307.1.3286338.

- Harris, Rivkah (1976). "On Foreigners in Old Babylonian Sippar". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 70 (2). Presses Universitaires de France: 145–152. JSTOR 23282311 . Retrieved 2021-10-06.

- Henkelman, Wouter F. M. (2008). The other gods who are: studies in Elamite-Iranian acculturation based on the Persepolis fortification texts. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. ISBN 978-90-6258-414-7.

- Jahangirfar, Milad (2018). "The Elamite Triads: Reflections on the Possible Continuities in Iranian Tradition". Iranica Antiqua. 53: 105–124. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- König, Friedrich Wilhelm (1965). Die Elamischen Königsinschriften. Selbstverlag des Herausgebers.

- Krebernik, Manfred (2016), "Zwillingsgottheiten", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), vol. 15, retrieved 2022-08-13

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (1980), "Ikšudu(m)", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, vol. 5, retrieved 2022-03-10

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (1983), "Lāgamāl", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, vol. 6, retrieved 2021-08-11

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (1987), "Lugal-šunugia", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, vol. 7, retrieved 2022-08-13

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (1987a), "Lulal/Lātarāk", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, vol. 7, retrieved 2021-10-04

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (2016). Ancient Mesopotamian Religion and Mythology: Selected Essays. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-153674-8. OCLC 945892683.

- Lambert, Wilfred G.; Winters, Ryan D. (2023). An = Anum and Related Lists. Mohr Siebeck. doi:10.1628/978-3-16-161383-8. ISBN 978-3-16-161383-8.

- Malbran-Labat, Florence (2018). "Elamite Royal Inscriptions". The Elamite World. Routledge. pp. 464–480. doi:10.4324/9781315658032-24. ISBN 9781315658032.

- Marchesi, Gianni; Marchetti, Nicoló (2019). "A babylonian official at Tilmen Höyük in the time of king Sumu-la-el of Babylon". Orientalia. 88 (1): 1–36. ISSN 0030-5367 . Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- Matthews, Victor H. (1978). "Government Involvement in the Religion of the Mari Kingdom". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 72 (2). Presses Universitaires de France: 151–156. JSTOR 23282224 . Retrieved 2021-10-06.

- Mofidi-Nasrabadi, Behzad (2021), "Haft Tappeh", Haft Tappeh (Probably Ancient Elamite City of Kabnak), The Encyclopedia of Ancient History: Asia and Africa, Wiley, pp. 1–7, doi:10.1002/9781119399919.eahaa00036, ISBN 9781119399919, S2CID 244582005

- Nakata, Ichiro (1975). "A Mari Note: Ikrub-El and Related Matters". Orient. 11. The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan: 15–24. doi: 10.5356/orient1960.11.15 . ISSN 1884-1392.

- Potts, Daniel (1999). The archaeology of Elam: formation and transformation of an ancient Iranian state. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-48961-7. OCLC 813439001.

- Potts, Daniel T. (2010). "Elamite Temple Building". From the foundations to the crenellations: essays on temple building in the Ancient Near East and Hebrew Bible. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86835-031-9. OCLC 618338811.

- Potts, Daniel T. (2018). "Ælam regio: Elam in Western scholarship from the Renaissance to the late 19th century". The Elamite World. Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 978-1-315-65803-2. OCLC 1022561448.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sasson, Jack M. (2001). "Ancestors Divine?" (PDF). In van Soldt, Wilfred H.; Dercksen, Jan G.; Kouwenberg, N. J. C.; Krispijn, Theo (eds.). Veenhof Anniversary Volume: Studies Presented to Klaas R. Veenhof on the Occasion of His Sixty-fifth Birthday. Pihans Series. Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. ISBN 978-90-6258-091-0 . Retrieved 2022-08-10.

- Sasson, Jack M. (2015). From the Mari Archives: an Anthology of Old Babylonian Letters. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-830-5. OCLC 907931488.

- van der Toorn, Karel (1995). "Migration and the Spread of Local Cults". Immigration and emigration within the ancient Near East: Festschrift E. Lipiński. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters en Departement Oriëntalistiek. ISBN 90-6831-727-X. OCLC 33242446.

- Wasserman, Nathan (2019). "The Susa Funerary Texts: A New Edition and Re-Evaluation and the Question of Psychostasia in Ancient Mesopotamia". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 139 (4). American Oriental Society. doi: 10.7817/jameroriesoci.139.4.0859 . ISSN 0003-0279.

- Wiggermann, Frans A. M. (1997). "Transtigridian Snake Gods". In Finkel, I. L.; Geller, M. J. (eds.). Sumerian Gods and their Representations. STYX Publications. ISBN 978-90-56-93005-9.