Related Research Articles

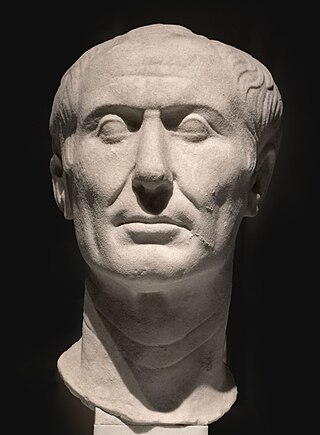

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and subsequently became dictator from 49 BC until his assassination in 44 BC. He played a critical role in the events that led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire.

Marcus Antonius, commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autocratic Roman Empire.

Plutarch was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his Parallel Lives, a series of biographies of illustrious Greeks and Romans, and Moralia, a collection of essays and speeches. Upon becoming a Roman citizen, he was possibly named Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus.

Marcus Junius Brutus was a Roman politician, orator, and the most famous of the assassins of Julius Caesar. After being adopted by a relative, he used the name Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus, which was retained as his legal name. He is often referred to simply as Brutus.

The Ides of March is the 74th day in the Roman calendar, corresponding to 15 March. It was marked by several religious observances and was a deadline for settling debts in Rome. In 44 BC, it became notorious as the date of the assassination of Julius Caesar, which made the Ides of March a turning point in Roman history.

The Second Triumvirate was an extraordinary commission and magistracy created for Mark Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian to give them practically absolute power. It was formally constituted by law on 27 November 43 BC with a term of five years; it was renewed in 37 BC for another five years before expiring in 32 BC. Constituted by the lex Titia, the triumvirs were given broad powers to make or repeal legislation, issue judicial punishments without due process or right of appeal, and appoint all other magistrates. The triumvirs also split the Roman world into three sets of provinces.

Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus was a general and politician of ancient Rome in the 1st century BC.

Gaius Cassius Longinus was a Roman senator and general best known as a leading instigator of the plot to assassinate Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC. He was the brother-in-law of Brutus, another leader of the conspiracy. He commanded troops with Brutus during the Battle of Philippi against the combined forces of Mark Antony and Octavian, Caesar's former supporters, and committed suicide after being defeated by Mark Antony.

Gaius Asinius Pollio was a Roman soldier, politician, orator, poet, playwright, literary critic, and historian, whose lost contemporaneous history provided much of the material used by the historians Appian and Plutarch. Pollio was most famously a patron of Virgil and a friend of Horace and poems to him were dedicated by both men.

Servilia was a Roman matron from a distinguished family, the Servilii Caepiones. She was the daughter of Quintus Servilius Caepio and Livia, thus the half-sister of Cato the Younger. She married Marcus Junius Brutus, with whom she had a son, the Brutus who, along with others in the Senate, would assassinate Julius Caesar. After her first husband's death in 77, she married Decimus Junius Silanus, and with him had a son and three daughters.

Porcia, occasionally spelled Portia, especially in 18th-century English literature, was a Roman woman who lived in the 1st century BC. She was the daughter of Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis and his first wife Atilia. She is best known for being the second wife of Marcus Junius Brutus, the most famous of Julius Caesar's assassins, and appears primarily in the letters of Cicero.

The Parallel Lives is a series of 48 biographies of famous men written by the Greco-Roman philosopher, historian, and Apollonian priest Plutarch, probably at the beginning of the second century. It is also known as Plutarch's Lives ; Parallels ; the Comparative Lives ; the Lives of Illustrious Men ; and the Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans. The lives are arranged in pairs to illuminate their common moral virtues or failings. The surviving Parallel Lives comprises 23 pairs of biographies, each pair consisting of one Greek and one Roman of similar destiny, such as Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar, or Demosthenes and Cicero. It is a work of considerable importance, not only as a source of information about the individuals described, but also about the times in which they lived.

Et tu, Brute? is a Latin phrase literally meaning "and you, Brutus?" or "also you, Brutus?", often translated as "You as well, Brutus?", "You too, Brutus?", or "Even you, Brutus?". The quote appears in Act 3 Scene 1 of William Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar, where it is spoken by the Roman dictator Julius Caesar, at the moment of his assassination, to his friend Marcus Junius Brutus, upon recognizing him as one of the assassins. The first known occurrences of the phrase are said to be in two earlier Elizabethan plays; Henry VI, Part 3 by Shakespeare, and an even earlier play, Caesar Interfectus, by Richard Edes. The phrase is often used apart from the plays to signify an unexpected betrayal by a friend.

Calpurnia was either the third or fourth wife of Julius Caesar, and the one to whom he was married at the time of his assassination. According to contemporary sources, she was a good and faithful wife, in spite of her husband's infidelity; and, forewarned of the attempt on his life, she endeavored in vain to prevent his murder.

Julia was the daughter of Roman dictator Julius Caesar and his first or second wife Cornelia, and his only child from his marriages. Julia became the fourth wife of Pompey the Great and was renowned for her beauty and virtue.

Julius Caesar was assassinated by a group of senators on the Ides of March of 44 BC during a meeting of the Senate at the Curia of Pompey of the Theatre of Pompey in Rome where the senators stabbed Caesar 23 times. They claimed to be acting over fears that Caesar's unprecedented concentration of power during his dictatorship was undermining the Roman Republic. At least 60 to 70 senators were party to the conspiracy, led by Marcus Junius Brutus, Gaius Cassius Longinus, and Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus. Despite the death of Caesar, the conspirators were unable to restore the institutions of the Republic. The ramifications of the assassination led to his martyrdom, the Liberators' civil war and ultimately to the Principate period of the Roman Empire.

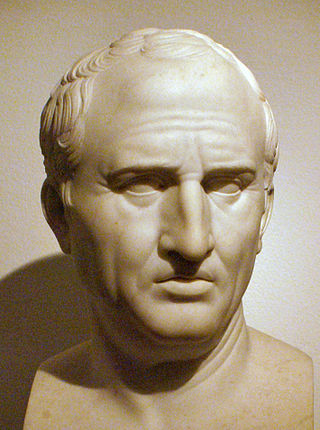

The personal life of Marcus Tullius Cicero provided the underpinnings of one of the most significant politicians of the Roman Republic. Cicero, a Roman statesman, lawyer, political theorist, philosopher, and Roman constitutionalist, played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. A contemporary of Julius Caesar, Cicero is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.

Marcus Favonius was a Roman politician during the period of the fall of the Roman Republic. He is noted for his imitation of Cato the Younger, his espousal of the Cynic philosophy, and for his appearance as the Poet in William Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar.

The military campaigns of Julius Caesar constituted both the Gallic Wars and Caesar's civil war. The Gallic War mainly took place in what is now France. In 55 and 54 BC, he invaded Britain, although he made little headway. The Gallic War ended with complete Roman victory at the Battle of Alesia. This was followed by the civil war, during which time Caesar chased his rivals to Greece, decisively defeating them there. He then went to Egypt, where he defeated the Egyptian pharaoh and put Cleopatra on the throne. He then finished off his Roman opponents in Africa and Hispania. Once his campaigns were over, he served as Roman dictator until his assassination on 15 March 44 BC. These wars were critically important in the transition of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire.

Julius Caesar's planned invasion of the Parthian Empire was to begin in 44 BC, but the Roman dictator's assassination that year prevented the invasion from taking place.

References

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 36.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 2, 36.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 46.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 27.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 28.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 29, 30.

- ↑ Erbse, "Die Bedeutung der Synkrisis", pp. 398–424.

- 1 2 Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 32.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 38–40.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 44–47.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 44–47.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 48, 49.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 52, 53.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 49, 50.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 43.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 50–52.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 48, 49.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 54–56.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 19, 20.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 20.

- 1 2 Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 23.

- ↑ Suetonius, Caesar, 76.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 18.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 30, 31.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 31.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 59, 60.

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Caesar, 3.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 23.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 60.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 61.

- ↑ Plato, Republic, viii. 569b.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 61.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 63, 64.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 64.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 65.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, p. 68.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 68, 69.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 73, 74.

- ↑ Pelling, Plutarch Caesar, pp. 75, 76.