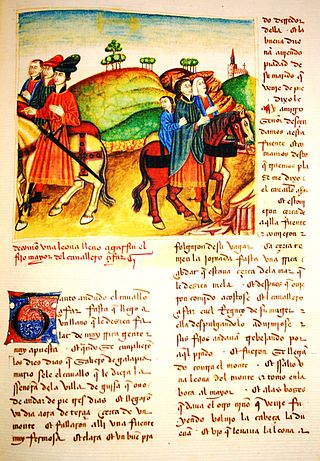

The Libro de los juegos, or Libro de axedrez, dados e tablas, was a Spanish treaty of chess which synthesized the information from other Arabic works on this same topic, dice and tables games, commissioned by Alfonso X of Castile, Galicia and León and completed in his scriptorium in Toledo in 1283. It contains the earliest European treatise on chess as well as being the oldest document on European tables games, and is an exemplary piece of the literary legacy of the Toledo School of Translators.

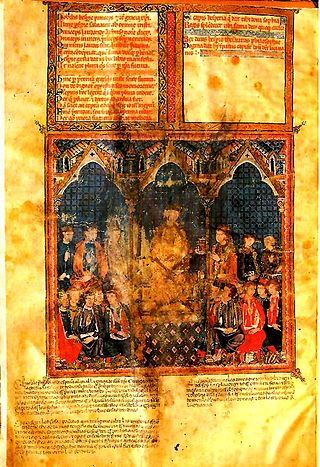

Alfonso X was King of Castile, León and Galicia from 1 June 1252 until his death in 1284. During the election of 1257, a dissident faction chose him to be king of Germany on 1 April. He renounced his claim to Germany in 1275, and in creating an alliance with the Kingdom of England in 1254, his claim on the Duchy of Gascony as well.

The Kingdom of Castile was a polity in the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. It traces its origins to the 9th-century County of Castile, as an eastern frontier lordship of the Kingdom of Asturias. During the 10th century, the Castilian counts increased their autonomy, but it was not until 1065 that it was separated from León and became a kingdom in its own right. Between 1072 and 1157, it was again united with León, and after 1230, the union became permanent.

Sancho Garcés VI, called the Wise was King of Navarre from 1150 until his death in 1194. He was the first monarch to officially drop the title of King of Pamplona in favour of King of Navarre, thus changing the designation of his kingdom. Sancho Garcés was responsible for bringing his kingdom into the political orbit of Europe. He was the eldest son of García Ramírez, the Restorer and Margaret of L'Aigle.

Don Juan Manuel was a Spanish medieval writer, nephew of Alfonso X of Castile, son of Manuel of Castile and Beatrice of Savoy. He inherited from his father the great Lordship of Villena, receiving the titles of Lord, Duke and lastly Prince of Villena. He married three times, choosing his wives for political and economic convenience, and worked to match his children with partners associated with royalty. Juan Manuel became one of the richest and most powerful men of his time, coining his own currency as the kings did. During his life, he was criticised for choosing literature as his vocation, an activity thought inferior for a nobleman of such prestige.

Enrique de Villena (1384–1434), also known as Henry de Villeine and Enrique de Aragón, was a Spanish nobleman, writer, theologian and poet. He was also the last legitimate member of the House of Barcelona, the former royal house of Aragon. When political power was denied to him, he turned to writing. He was persecuted by Alfonso V of Aragon and John II of Castile owing to his reputation as a necromancer.

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and León upon the accession of the then Castilian king, Ferdinand III, to the vacant Leonese throne. It continued to exist as a separate entity after the personal union in 1469 of the crowns of Castile and Aragon with the marriage of the Catholic Monarchs up to the promulgation of the Nueva Planta decrees by Philip V in 1716.

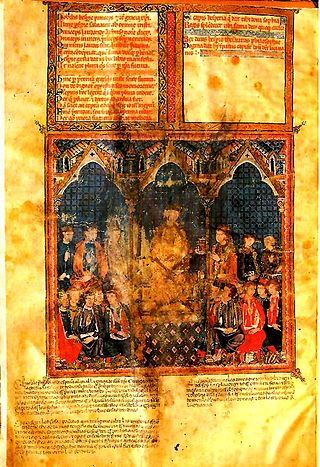

The Siete Partidas or simply Partidas, was a Castilian statutory code first compiled during the reign of Alfonso X of Castile (1252–1284), with the intent of establishing a uniform body of normative rules for the kingdom. The codified and compiled text was originally called the Libro de las Leyes. It was not until the 14th century that it was given its present name, referring to the number of sections into which it is divided.

Gregorio López was a president of the Consejo de Indias, humanist, jurist and lawyer.

Francisco Xavier Martínez Marina was a noted Spanish jurist, historian and priest.

Antonio García de Solalinde was a writer, professor and philologist.

The Toledo School of Translators is the group of scholars who worked together in the city of Toledo during the 12th and 13th centuries, to translate many of the Islamic philosophy and scientific works from Classical Arabic into Medieval Latin.

The Estoria de España, also known in the 1906 edition of Ramón Menéndez Pidal as the Primera Crónica General, is a history book written on the initiative of Alfonso X of Castile "El Sabio", reigned 1252-1284, and who was actively involved in the chronicle's editing. It is believed to be the first extended history of Spain in Old Spanish, a West Iberian Romance language that forms part of the lineage from Vulgar Latin to modern Spanish. Many prior works were consulted in constructing this history.

The Tower of Mendoza is a tower located in Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain. It was declared Bien de Interés Cultural in 1984. The tower is strategically located between the roads of Old Castile and the Ebro river.

Medieval Spanish literature consists of the corpus of literary works written in Old Spanish between the beginning of the 13th and the end of the 15th century. Traditionally, the first and last works of this period are taken to be respectively the Cantar de mio Cid, an epic poem whose manuscript dates from 1207, and La Celestina (1499), a work commonly described as transitional between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

The General estoria is a universal history written on the initiative of Alfonso X of Castile (1252–1284), known as el Sabio. The work was written in Old Spanish, a novelty in this historiographical genre, up until then regularly written in Latin. The work intended to narrate the world’s history from the beginnings until the time of Alfonso, but it was never completed. The extant work covers from the creation until the birth of the virgin Mary, in the biblical section, and until year zero, in the history of the non-Jewish peoples. For the writing of this huge work, many older books were used as sources. Most of them were written in Latin, but there were French and Arabic sources, as well.

Rabbi Zag de Sujurmenza was a Jewish convert of 13th-century Spain who helped King Alfonso X of Castile with his scientific works.

The Libros del saber de astronomía, literally "book[s] of the wisdom of astronomy [astrology]", is a series of books of the medieval period, composed during the reign of Alfonso X of Castile. They describe the celestial bodies and the astronomical instruments existing at the time. The collection is a group of treatises on astronomical instruments, like the celestial sphere, the spherical and plane astrolabe, saphea, and universal plate for all latitudes, for uranography or star cartography that can be used for casting horoscopes. The purpose of the rest of the instruments, the quadrant of the type called vetus, sundial, clepsydras, is to determine the time, which was also needed to cast the horoscope. The king looked for separate works for the construction and use of each device.

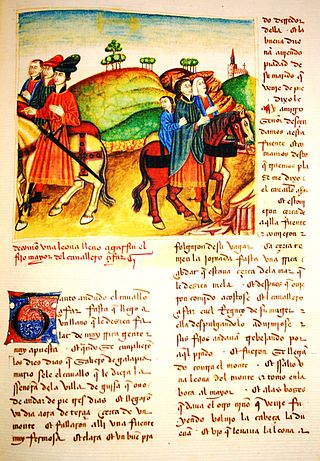

The Gran conquista de Ultramar is a late 13th-century Castilian chronicle of the Crusades for the period 1095–1271. It is a work of compilation, translation and prosification of Old French and Old Occitan sources, mixing historical material with legends drawn from the epic chansons de geste. It was produced under royal patronage by Sancho IV and probably his father, Alfonso X.

Jesús Rodríguez-Velasco is a Spanish-American philologist and medievalist. He currently holds the position of Augustus R. Street Professor of Spanish & Portuguese and Comparative Literature at Yale University. He is best known for his work on Chivalry in Castille, and on his approach to Law and literature, most notably, in his scholarly work on the Siete partidas. He is one of the executive directors of the Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies. In 2010, he received the John K. Walsh award for his article "La urgente presencia de las Siete Partidas".