The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, also known as the Church of the Resurrection, is a fourth-century church in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. It is considered to be the holiest site for Christians in the world, as it has been the most important pilgrimage site for Christianity since the fourth century.

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica was a large public building with multiple functions that was typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek East. The building gave its name to the architectural form of the basilica.

A tomb is a repository for the remains of the dead. It is generally any structurally enclosed interment space or burial chamber, of varying sizes. Placing a corpse into a tomb can be called immurement, although this word mainly means entombing people alive, and is a method of final disposition, as an alternative to cremation or burial.

The Catacombs of Rome are ancient catacombs, underground burial places in and around Rome, of which there are at least forty, some rediscovered only in recent decades.

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be considered a type of tomb, or the tomb may be considered to be within the mausoleum.

Early Christian art and architecture is the art produced by Christians, or under Christian patronage, from the earliest period of Christianity to, depending on the definition, sometime between 260 and 525. In practice, identifiably Christian art only survives from the 2nd century onwards. After 550, Christian art is classified as Byzantine, or according to region.

Saint Peter's tomb is a site under St. Peter's Basilica that includes several graves and a structure said by Vatican authorities to have been built to memorialize the location of Saint Peter's grave. St. Peter's tomb is alleged near the west end of a complex of mausoleums, the Vatican Necropolis, that date between about AD 130 and AD 300. The complex was partially torn down and filled with earth to provide a foundation for the building of the first St. Peter's Basilica during the reign of Constantine I in about AD 330. Though many bones have been found at the site of the 2nd-century shrine, as the result of two campaigns of archaeological excavation, Pope Pius XII stated in December 1950 that none could be confirmed to be Saint Peter's with absolute certainty. Following the discovery of bones that had been transferred from a second tomb under the monument, on June 26, 1968, Pope Paul VI said that the relics of Saint Peter had been identified in a manner considered convincing. Only circumstantial evidence was provided to support the claim.

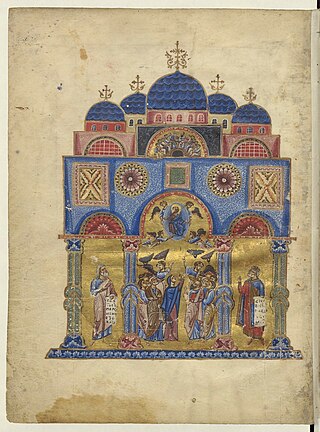

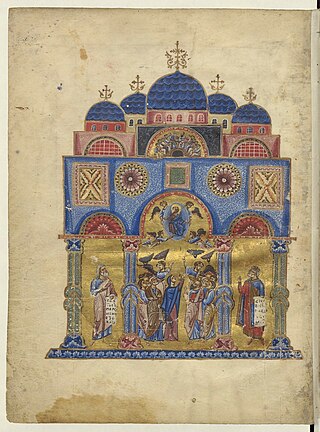

The Church of the Holy Apostles, also known as the Imperial Polyandrion, was a Byzantine Eastern Orthodox church in Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. The first structure dated to the 4th century, though future emperors would add to and improve upon it. It was second in size and importance only to the Hagia Sophia among the great churches of the capital.

A crux gemmata is a form of cross typical of Early Christian and Early Medieval art, where the cross, or at least its front side, is principally decorated with jewels. In an actual cross, rather than a painted image of one, the reverse side often has engraved images of the Crucifixion of Jesus or other subjects.

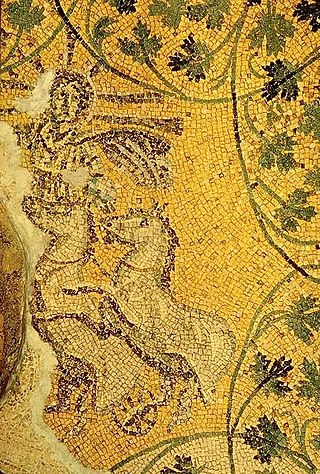

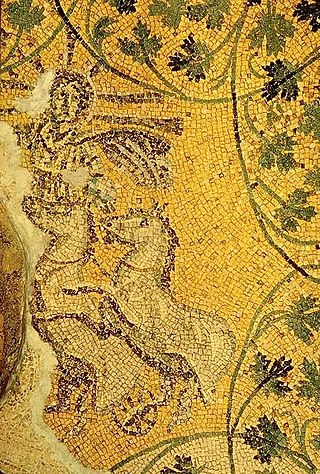

Santa Costanza is a 4th-century church in Rome, Italy, on the Via Nomentana, which runs north-east out of the city. It is a round building with well preserved original layout and mosaics. It has been built adjacent to a horseshoe-shaped church, now in ruins, which has been identified as the initial 4th-century cemeterial basilica of Saint Agnes. Santa Costanza and the old Saint Agnes were both constructed over the earlier catacombs in which Saint Agnes is believed to be buried.

The Vatican Necropolis lies under the Vatican City, at depths varying between 5–12 metres below Saint Peter's Basilica. The Vatican sponsored archaeological excavations under Saint Peter's in the years 1940–1949 which revealed parts of a necropolis dating to Imperial times. The work was undertaken at the request of Pope Pius XI who wished to be buried as close as possible to Peter the Apostle. It is also home to the Tomb of the Julii, which has been dated to the third or fourth century. The necropolis was not originally one of the Catacombs of Rome, but an open-air cemetery with tombs and mausolea.

The Chapel of the Ascension is a chapel and shrine located on the Mount of Olives, in the At-Tur district of Jerusalem. Part of a larger complex consisting first of a Christian church and monastery, then an Islamic mosque, Zawiyat al-Adawiya, it is located on a site traditionally believed to be the earthly spot where Jesus ascended into Heaven after his Resurrection. It houses a slab of stone believed to contain one of his footprints. This article deals with two sites, the Christian site of the Ascension, and the adjacent but separate mosque built over an ancient grave.

The basilica of Santo Stefano encompasses a complex of religious edifices in the city of Bologna, Italy. Located on Piazza Santo Stefano, it is locally known as Sette Chiese and Santa Gerusalemme. It has the dignity of minor basilica.

The Catacombs of San Sebastiano are a hypogeum cemetery in Rome, Italy, rising along Via Appia Antica, in the Ardeatino Quarter. It is one of the very few Christian burial places that has always been accessible. The first of the former four floors is now almost completely destroyed.

Domes were a characteristic element of the architecture of Ancient Rome and of its medieval continuation, the Byzantine Empire. They had widespread influence on contemporary and later styles, from Russian and Ottoman architecture to the Italian Renaissance and modern revivals. The domes were customarily hemispherical, although octagonal and segmented shapes are also known, and they developed in form, use, and structure over the centuries. Early examples rested directly on the rotunda walls of round rooms and featured a central oculus for ventilation and light. Pendentives became common in the Byzantine period, provided support for domes over square spaces.

The early domes of the Middle Ages, particularly in those areas recently under Byzantine control, were an extension of earlier Roman architecture. The domed church architecture of Italy from the sixth to the eighth centuries followed that of the Byzantine provinces and, although this influence diminishes under Charlemagne, it continued on in Venice, Southern Italy, and Sicily. Charlemagne's Palatine Chapel is a notable exception, being influenced by Byzantine models from Ravenna and Constantinople. The Dome of the Rock, an Umayyad Muslim religious shrine built in Jerusalem, was designed similarly to nearby Byzantine martyria and Christian churches. Domes were also built as part of Muslim palaces, throne halls, pavilions, and baths, and blended elements of both Byzantine and Persian architecture, using both pendentives and squinches. The origin of the crossed-arch dome type is debated, but the earliest known example is from the tenth century at the Great Mosque of Córdoba. In Egypt, a "keel" shaped dome profile was characteristic of Fatimid architecture. The use of squinches became widespread in the Islamic world by the tenth and eleventh centuries. Bulbous domes were used to cover large buildings in Syria after the eleventh century, following an architectural revival there, and the present shape of the Dome of the Rock's dome likely dates from this time.

The symbolic meaning of the dome has developed over millennia. Although the precise origins are unknown, a mortuary tradition of domes existed across the ancient world, as well as a symbolic association with the sky. Both of these traditions may have a common root in the use of the domed hut, a shape which was associated with the heavens and translated into tombs.

The Church of the Seat of Mary, Church of the Kathisma or Old Kathisma being the name mostly used in literature, was a 5th-century Byzantine church in the Holy Land, located between Jerusalem and Bethlehem, on what is today known as Hebron Road. It was built on the alleged resting place of Mary on the road to Bethlehem mentioned in the apocryphal Proto-Gospel of James. The church was built when Marian devotion first rose to great importance, following the First Council of Ephesus of 431. It is one of the earliest churches known to have been dedicated to the Theotokos in the entire Byzantine Empire.

The Christianization of Iberia refers to the spread of Christianity in the early 4th century by the sermon of Saint Nino in an ancient Georgian kingdom of Kartli, known as Iberia in classical antiquity, which resulted in declaring it as a state religion by then-pagan King Mirian III of Iberia. Per Sozomen, this led the king's "large and warlike barbarian nation to confess Christ and renounce the religion of their fathers", as the polytheistic Georgians had long-established anthropomorphic idols, known as the "Gods of Kartli". The king would become the main sponsor, architect, initiator and an organizing power of all building processes. Per Socrates of Constantinople, the "Iberians first embraced the Christian faith" alongside the Abyssinians, but the exact date of an event is still debated. Georgian monarchs, alongside the Armenians, were among the first anywhere in the world to convert to a Christian faith. Prior to the escalation of Armeno-Georgian ecclesiastical rivalry and the christological controversies their Caucasian Christianity was extraordinarily inclusive, pluralistic and flexible that only saw the rigid ecclesiological hierarchies established much later, particularly as "national" churches crystallized from the 6th century. Despite the tremendous diversity of the region, the christianization process was a pan-regional and a cross-cultural phenomenon in the Caucasus, Eurasia's most energetic and cosmopolitan zones throughout the late antiquity, hard enough to place Georgians and Armenians unequivocally within any one major civilization. The Jews of Mtskheta, the royal capital of Kartli, that did play a significant role in the Christianization of the kingdom, would give a strong impetus to deepen the ties between the Georgian monarchy and the Holy Land leading to an increasing presence of Georgians in Palestine, as the activities of Peter the Iberian and other pilgrims confirm, including the oldest attested Georgian Bir el Qutt inscriptions found in the Judaean Desert alongside the pilgrim graffiti of Nazareth and Sinai.

The Mausoleum of Honorius was a late antique circular mausoleum and the burial place of the Roman emperor Honorius and other 5th-century imperial family members. Constructed for the Augustus of the western Roman Empire beside Old St Peter's Basilica in Rome, the Mausoleum of Honorius was the last Roman imperial mausoleum built.