The Nonintercourse Act is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set Amerindian boundaries of reservations. The various Acts were also intended to regulate commerce between settlers and the natives. The most notable provisions of the Act regulate the inalienability of aboriginal title in the United States, a continuing source of litigation for almost 200 years. The prohibition on purchases of Indian lands without the approval of the federal government has its origins in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783.

Terence Thomas Evans was a judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit and a United States district judge for the Eastern District of Wisconsin. Earlier in his career, he was a Wisconsin Circuit Court Judge in Milwaukee County.

Richard Miles Berman is a Senior United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York.

Dennis Jacobs is a Senior United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

Bigby v. Dretke 402 F.3d 551, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit heard a case appealed from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas on the issue of the instructions given to a jury in death penalty sentencing. The decision took into account the recent United States Supreme Court decisions concerning the relevance of mitigating evidence in sentencing, as in Penry v. Lynaugh.

Carcieri v. Salazar, 555 U.S. 379 (2009), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the federal government could not take land into trust that was acquired by the Narragansett Tribe in the late 20th century, as it was not federally recognized until 1983. While well documented in historic records and surviving as a community, the tribe was largely dispossessed of its lands while under guardianship by the state of Rhode Island before suing in the 20th century.

Okla. Tax Commission v. Citizen Band, Potawatomi Indian Tribe of Okla., 498 U.S. 505 (1991), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the tribe was not subject to state sales taxes on sales made to tribal members, but that they were liable for taxes on sales to non-tribal members.

The United States was the first jurisdiction to acknowledge the common law doctrine of aboriginal title. Native American tribes and nations establish aboriginal title by actual, continuous, and exclusive use and occupancy for a "long time." Individuals may also establish aboriginal title, if their ancestors held title as individuals. Unlike other jurisdictions, the content of aboriginal title is not limited to historical or traditional land uses. Aboriginal title may not be alienated, except to the federal government or with the approval of Congress. Aboriginal title is distinct from the lands Native Americans own in fee simple and occupy under federal trust.

Oneida Indian Nation of New York v. County of Oneida, 414 U.S. 661 (1974), is a landmark decision by the United States Supreme Court concerning aboriginal title in the United States. The original suit in this matter was the first modern-day Native American land claim litigated in the federal court system rather than before the Indian Claims Commission. It was also the first to go to final judgement.

County of Oneida v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York State, 470 U.S. 226 (1985), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case concerning aboriginal title in the United States. The case, sometimes referred to as Oneida II, was "the first Indian land claim case won on the basis of the Nonintercourse Act."

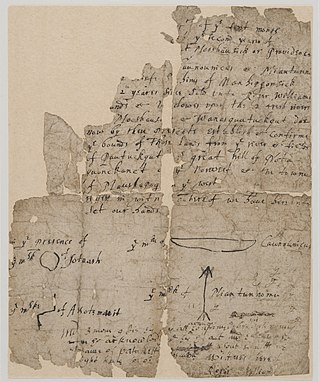

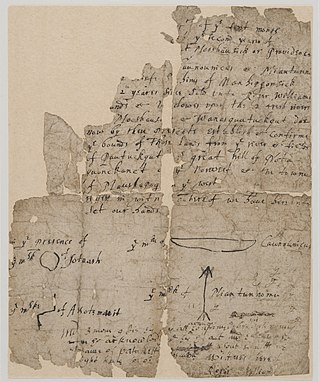

Joint Tribal Council of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton, 528 F.2d 370, was a landmark decision regarding aboriginal title in the United States. The United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit held that the Nonintercourse Act applied to the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot, non-federally-recognized Indian tribes, and established a trust relationship between those tribes and the federal government that the State of Maine could not terminate.

Cayuga Indian Nation of New York v. Pataki, 413 F.3d 266, is an important precedent in the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit for the litigation of aboriginal title in the United States. Applying the U.S. Supreme Court's recent ruling in City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York (2005), a divided panel held that the equitable doctrine of laches bars all tribal land claims sounding in ejectment or trespass, for both tribal plaintiffs and the federal government as plaintiff-intervenor.

Aboriginal title in California refers to the aboriginal title land rights of the indigenous peoples of California. The state is unique in that no Native American tribe in California is the counterparty to a ratified federal treaty. Therefore, all the Indian reservations in the state were created by federal statute or executive order.

The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe is one of two federally recognized tribes of Wampanoag people in Massachusetts. Recognized in 2007, they are headquartered in Mashpee on Cape Cod. The other Wampanoag tribe is the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) on Martha's Vineyard.

Selle v. Gibb, 741 F.2d 896 was a landmark ruling on the doctrine of striking similarities. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit ruled that while copying must be proved by access and substantial similarity, where evidence of access does not exist, striking similarities may raise an inference of copying by showing that the work could not have been the result of independent creation, coincidence, or common source. Striking similarity alone is not enough to infer access. The similarity must preclude independent creation in order to infer access.

Miller v. Universal City Studios, Inc., is a case where an appeals court found that although the plaintiff apparently deserved to prevail, it reversed the jury verdict and remanded the case for retrial because it found reversible error in the trial judges' instructions to the jury. The appellate court found that the judge's jury instructions, which included the statement that the labor of research by an author is protected by copyright, had been given in error. The court noted that plaintiff, over the objection of the defense, had urged the district court judge to include this instruction.

Mt. Healthy City School District Board of Education v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 (1977), often shortened to Mt. Healthy v. Doyle, was a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court decision arising from a fired teacher's lawsuit against his former employer, the Mount Healthy City Schools. The Court considered three issues: whether federal-question jurisdiction existed in the case, whether the Eleventh Amendment barred federal lawsuits against school districts, and whether the First and Fourteenth Amendments prevented the district, as a government agency, from firing or otherwise disciplining an employee for constitutionally protected speech on a matter of public concern where the same action might have taken place for other, unprotected activities. Justice William Rehnquist wrote the opinion.

Marcus Gray et al. v. Katy Perry et al. was a copyright infringement lawsuit against Katy Perry, Jordan Houston, Lukasz Gottwald, Karl Martin Sandberg, Henry Russell Walter ("Cirkut"), Capitol Records and others, in which the plaintiffs Marcus Gray ("Flame"), Emanuel Lambert and Chike Ojukwu alleged that Perry's song "Dark Horse" infringed their exclusive rights in their song "Joyful Noise" pursuant to 17 U.S.C § 106. The focus of the similarity was a short descending pattern known in music as an "ostinato". In both songs, a short ostinato is used repeatedly to form part of the beat of each song and both ostinatos share similar descending shapes. Gray et al. claimed that the instrumental beat of the ostinato in "Joyful Noise" was protectable original expression and that Perry et al. had access to and copied the ostinato when composing "Dark Horse." On March 16, 2020, Judge Christina A. Snyder ultimately found that Gray et al. had failed to satisfy the extrinsic test for substantial similarity, overturning a previous jury verdict which had sided with the plaintiffs. Snyder's ruling was affirmed on appeal.

United States v. Moylan, 417 F.2d 1002, 1003, was a United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit case affirming a district court's refusal to permit defense counsel to argue for jury nullification.