Related Research Articles

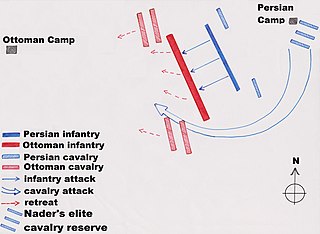

The Battle of Karnal was a decisive victory for Nader Shah, the founder of the Afsharid dynasty of Iran, during his invasion of India. Nader's forces defeated the army of Muhammad Shah within three hours, paving the way for the Iranian sack of Delhi. The engagement is considered the crowning jewel in Nader's military career as well as a tactical masterpiece. The battle took place near Karnal in Haryana, 110 kilometres (68 mi) north of Delhi, India.

The Afsharid dynasty was an Iranian dynasty founded by Nader Shah of the Qirqlu clan of the Turkoman Afshar tribe, ruling over the Afsharid Empire.

Ali-qoli Khan, commonly known by his regnal title Adel Shah was the second shah of Afsharid Iran, ruling from 1747 to 1748. He was the nephew and successor of Nader Shah, the founder of the Afsharid dynasty.

Yeprem Khan, born Yeprem Davidyan, was an Iranian-Armenian member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), revolutionary leader and a leading figure in the Constitutional Revolution of Iran.

The Persian Constitutional Revolution, also known as the Constitutional Revolution of Iran, took place between 1905 and 1911 during the Qajar dynasty. The revolution led to the establishment of a parliament in Persia (Iran), and has been called an "epoch-making episode in the modern history of Persia".

The Battle of Gulnabad was fought between the military forces from Hotaki Dynasty and the army of the Safavid Empire on Sunday, March 8, 1722. It further cemented the eventual fall of the Safavid dynasty, which had been declining for decades.

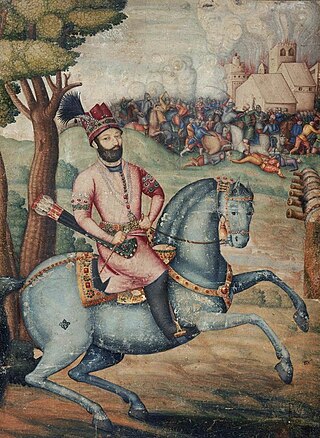

Nader Shah Afshar was the founder of the Afsharid dynasty of Iran and one of the most powerful rulers in Iranian history, ruling as shah of Iran (Persia) from 1736 to 1747, when he was assassinated during a rebellion. He fought numerous campaigns throughout the Middle East, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and South Asia, such as the battles of Herat, Mihmandust, Murche-Khort, Kirkuk, Yeghevārd, Khyber Pass, Karnal, and Kars. Because of his military genius, some historians have described him as the Napoleon of Persia, the Sword of Persia, or the Second Alexander. Nader belonged to the Turkoman Afshars, one of the seven Qizilbash tribes that helped the Safavid dynasty establish their power in Iran.

The siege of Kandahar began when Nader Shah's Afsharid army invaded southern Afghanistan to topple the last Hotaki stronghold of Loy Kandahar, which was held by Hussain Hotaki. It took place in the Old Kandahar area of the modern city of Kandahar in Afghanistan and lasted until March 24, 1738, when the Hotaki Afghans were defeated by the Persian army.

Emperor Nader Shah, the Shah of Iran (1736–1747) and the founder of the Afsharid dynasty, invaded Northern India, eventually attacking Delhi in March 1739. His army had easily defeated the Mughals at the Battle of Karnal and would eventually capture the Mughal capital in the aftermath of the battle.

The siege of Isfahan was a six-month-long siege of Isfahan, the capital of the Safavid dynasty of Iran, by the Hotaki-led Afghan army. It lasted from March to October 1722 and resulted in the city's fall and the beginning of the end of the Safavid dynasty.

The Battle of Yeghevārd, also known as the Battle of Baghavard or Morad Tapeh, was the final major engagement of the Perso-Ottoman War of 1730–1735 where the principal Ottoman army in the Caucasus theatre under Koprulu Pasha's command was utterly destroyed by only the advance guard of Nader's army before the main Persian army could enter into the fray. The complete rout of Koprulu Pasha's forces led to a number of besieged Ottoman strongholds in the theatre surrendering as any hope of relief proved ephemeral in light of the crushing defeat at Yeghevārd. One of Nader's most impressive battlefield victories, in which he decimated a force four or five times the size of his own, it helped establish his reputation as a military genius and stands alongside many of his other great triumphs such as at Karnal, Mihmandoost or Kirkuk.

The Battle of Kirkuk, also known as the Battle of Agh-Darband, was the last battle in Nader Shah's Mesopotamian campaign where he avenged his earlier defeat at the hands of the Ottoman general Topal Osman Pasha, in which Nader achieved suitable revenge after defeating and killing him at the battle of Kirkuk. The battle was another in the chain of seemingly unpredictable triumphs and tragedies for both sides as the war swung wildly from the favour of one side to the other. Although the battle ended in a crushing victory for the Persians, they had to be withdrawn from the area due to a growing rebellion in the south of Persia led by Mohammad Khan Baluch. This rebellion in effect robbed Nader of the strategic benefits of his great victory which would have included the capture of Baghdad, if he had the chance to resume his campaign.

The Battle of Samarra was the key engagement between the two great generals Nader Shah and Topal Osman Pasha, which led to the siege of Baghdad being lifted, keeping Ottoman Iraq under Istanbul's control. The armed contest between the two colossi was very hard fought with a total of roughly 50,000 men becoming casualties by the end of the fighting that left the Persians decimated and the Ottoman victors badly shaken. Other than its importance in deciding the fate of Baghdad, the battle is also significant as Nader's only battlefield defeat although he would avenge this defeat at the hands of Topal Pasha at the Battle of Agh-Darband where Topal was killed.

The Battle of Kars was the last major engagement of the Ottoman-Persian War. The battle resulted in the complete and utter destruction of the Ottoman army. It was also the last of the great military triumphs of Nader Shah. The battle was in fact fought over a period of ten days in which the first day saw the Ottomans routed from the field, followed by a series of subsequent blockades and pursuits until the final destruction of the Ottoman army. The severity of the defeat, in conjunction with another defeat near Mosul, ended any hopes of Ottoman victory and forced them to enter into negotiations with a significantly weaker position than they would otherwise have occupied.

Nader's Dagestan campaign, were the campaigns conducted by the Persian Empire under its Afsharid ruler Nader Shah between the years 1741 and 1743 in order to fully subjugate the Dagestan region in the North Caucasus Area. The conflict between the Persian Empire & the Lezgins and a myriad of other Caucasian tribes in the north was intermittently fought through the mid-1730s during Nader's first short expedition in the Caucasus until the last years of his reign and assassination in 1747 with minor skirmishes and raids. The incredibly difficult terrain of the northern Caucasus region made the task of subduing the Lezgins an extremely challenging one. Despite this Nader Shah gained numerous strongholds and fortresses from the Dagestanis and pushed them to the very verge of defeat. The Lezgins however held on in the northernmost reaches of Dagestan and continued to defy Persian domination.

The military forces of the Afsharid dynasty of Iran had their origins in the relatively obscure yet bloody inter-factional violence in Khorasan during the collapse of the Safavid state. The small band of warriors under local warlord Nader Qoli of the Turkoman Afshar tribe in north-east Iran were no more than a few hundred men. Yet at the height of Nader's power as the king of kings, Shahanshah, he commanded an army of 375,000 fighting men which, according to Axworthy, constituted the single most powerful military force of its time, led by one of the most talented and successful military leaders of history.

The Sindh expedition was one of Nader Shah's last campaigns during his war in northern India. After his victory over Muhammad Shah, the Mughal emperor, Nader had compelled him to cede all the lands to the west of the Indus River. His return to this region from Delhi was honoured by all the governors of the newly annexed territories save for Khudayar Khan, ruler of Sindh, who was conspicuously absent despite being given a summons like the rest of the governors.

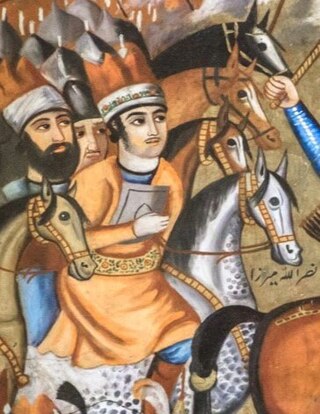

Morteza Mirza Afshar was an Afsharid prince and the son of Nader Shah of Persia, who was renamed Nasrollah Mirza in honour of his role in the victory at Karnal. He proved to be a talented military leader and demonstrated his worth during the battle of Karnal by commanding the centre of the Persian army which defeated Sa'adat Khan's forces and captured his person.

The Withdrawal through Andalal by the Persian army under Nader Shah took place after he broke off the siege of the last Lezgian fortress in order to return to Derbent for winter quarters. His withdrawal came under heavy raids by the Lezgians. However, there is no mention of any pitched battle around Andalal, or anywhere else during the withdrawal, in any of the primary or secondary material in the established historiography of Nader's Campaigns.

The Guarded Domains of Iran, commonly referred to as Afsharid Iran or the Afsharid Empire, was an Iranian empire established by the Turkoman Afshar tribe in Iran's north-eastern province of Khorasan, establishing the Afsharid dynasty that would rule over Iran during the mid-eighteenth century. The dynasty's founder, Nader Shah, was a successful military commander who deposed the last member of the Safavid dynasty in 1736, and proclaimed himself Shah.

References

- ↑ "Michael Axworthy, diplomat who became one of the world's leading authorities on Iran – obituary". The Telegraph. 3 April 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Axworthy, Dr Michael George Andrew" . Who's Who. 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Abrahamian, Ervand (4 April 2013). "Revolutionary Iran: A History of the Islamic Republic by Michael Axworthy". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Michael Axworthy". Capel and Land. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- 1 2 "Dr Michael Axworthy MA, PhD, FRSA, FRAS". Peterhouse. 18 March 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 "This House believes that Iran poses the greatest threat to security in the region". The Doha Debates. 28 March 2006. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ Floor, Willem (Autumn 2007). "The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant.(Book review)". The Middle East Journal. 61 (4): 748–9. JSTOR 4330478.

- ↑ Tonkin, Boyd (27 February 2009). "Iran: Empire of the Mind, By Michael Axworthy" . The Independent. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022.

- ↑ Buchan, James (1 March 2013). "Revolutionary Iran: A History of the Islamic Republic by Michael Axworthy – review". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- 1 2 "Dr. Michael Axworthy". Exeter University. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ "Michael Axworthy". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ Ansari, Ali. "Dr Michael Axworthy, FRSA, FRAS (1962-2019)". British Institute of Persian Studies. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ↑ Kelly, Stuart (16 November 2008). "Book review: Iran: Empire of the Mind". The Scotsman. Retrieved 13 June 2015.