In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.

Magnesium hydroxide is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula Mg(OH)2. It occurs in nature as the mineral brucite. It is a white solid with low solubility in water (Ksp = 5.61×10−12). Magnesium hydroxide is a common component of antacids, such as milk of magnesia.

Brucite is the mineral form of magnesium hydroxide, with the chemical formula Mg(OH)2. It is a common alteration product of periclase in marble; a low-temperature hydrothermal vein mineral in metamorphosed limestones and chlorite schists; and formed during serpentinization of dunites. Brucite is often found in association with serpentine, calcite, aragonite, dolomite, magnesite, hydromagnesite, artinite, talc and chrysotile.

Wüstite is a mineral form of mostly iron(II) oxide found with meteorites and native iron. It has a grey colour with a greenish tint in reflected light. Wüstite crystallizes in the isometric-hexoctahedral crystal system in opaque to translucent metallic grains. It has a Mohs hardness of 5 to 5.5 and a specific gravity of 5.88. Wüstite is a typical example of a non-stoichiometric compound.

Magnesium carbonate, MgCO3, is an inorganic salt that is a colourless or white solid. Several hydrated and basic forms of magnesium carbonate also exist as minerals.

Cement chemist notation (CCN) was developed to simplify the formulas cement chemists use on a daily basis. It is a shorthand way of writing the chemical formula of oxides of calcium, silicon, and various metals.

The chlorites are the group of phyllosilicate minerals common in low-grade metamorphic rocks and in altered igneous rocks. Greenschist, formed by metamorphism of basalt or other low-silica volcanic rock, typically contains significant amounts of chlorite.

Cummingtonite is a metamorphic amphibole with the chemical composition (Mg,Fe2+

)

2(Mg,Fe2+

)

5Si

8O

22(OH)

2, magnesium iron silicate hydroxide.

Serpentinization is a hydration and metamorphic transformation of ferromagnesian minerals, such as olivine and pyroxene, in mafic and ultramafic rock to produce serpentinite. Minerals formed by serpentinization include the serpentine group minerals, brucite, talc, Ni-Fe alloys, and magnetite. The mineral alteration is particularly important at the sea floor at tectonic plate boundaries.

Lime is an inorganic material composed primarily of calcium oxides and hydroxides. It is also the name for calcium oxide which is used as an industrial mineral and is made by heating calcium carbonate in a kiln. Calcium oxide can occur as a product of coal-seam fires and in altered limestone xenoliths in volcanic ejecta. The International Mineralogical Association recognizes lime as a mineral with the chemical formula of CaO. The word lime originates with its earliest use as building mortar and has the sense of sticking or adhering.

An AFm phase is an "alumina, ferric oxide, monosubstituted" phase, or aluminate ferrite monosubstituted, or Al2O3, Fe2O3 mono, in cement chemist notation (CCN). AFm phases are important hydration products in the hydration of Portland cements and hydraulic cements.

Thaumasite is a calcium silicate mineral, containing Si atoms in unusual octahedral configuration, with chemical formula Ca3Si(OH)6(CO3)(SO4)·12H2O, also sometimes more simply written as CaSiO3·CaCO3·CaSO4·15H2O.

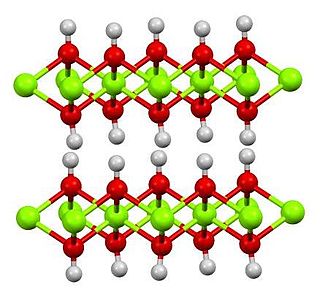

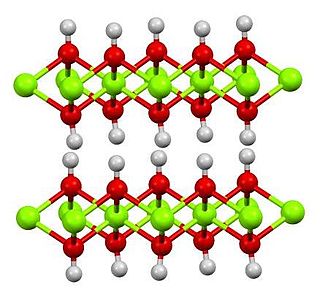

Layered double hydroxides (LDH) are a class of ionic solids characterized by a layered structure with the generic layer sequence [AcB Z AcB]n, where c represents layers of metal cations, A and B are layers of hydroxide anions, and Z are layers of other anions and neutral molecules. Lateral offsets between the layers may result in longer repeating periods.

Fougèrite is a relatively recently described naturally occurring green rust mineral. It is the archetype of the fougèrite group in the larger hydrotalcite supergroup of naturally occurring layered double hydroxides. The structure is based on brucite-like layers containing Fe2+ and Fe3+ cations, O2− and OH− anions, with loosely bound [CO3]2− groups and H2O molecules between the layers. Fougèrite crystallizes in trigonal system. The ideal formula for fougèrite is [Fe2+4Fe3+2(OH)12][CO3]·3H2O. Higher degrees of oxidation produce the other members of the fougèrite group, namely trébeurdenite, [Fe2+2Fe3+4O2(OH)10][CO3]·3H2O and mössbauerite, [Fe3+6O4(OH)8][CO3]·3H2O.

The alkali–carbonate reaction is an alteration process first suspected in the 1950s in Canada for the degradation of concrete containing dolomite aggregates.

Concrete degradation may have many different causes. Concrete is mostly damaged by the corrosion of reinforcement bars due to the carbonatation of hardened cement paste or chloride attack under wet conditions. Chemical damage is caused by the formation of expansive products produced by chemical reactions, by aggressive chemical species present in groundwater and seawater, or by microorganisms Other damaging processes can also involve calcium leaching by water infiltration, physical phenomena initiating cracks formation and propagation, fire or radiant heat, aggregate expansion, sea water effects, leaching, and erosion by fast-flowing water.

Népouite is a rare nickel silicate mineral which has the apple green color typical of such compounds. It was named by the French mining engineer Edouard Glasser in 1907 after the place where it was first described, the Népoui Mine, Népoui, Poya Commune, North Province, New Caledonia. The ideal formula is Ni3(Si2O5)(OH)4, but most specimens contain some magnesium, and (Ni,Mg)3(Si2O5)(OH)4 is more realistic. There is a similar mineral called lizardite in which all of the nickel is replaced by magnesium, formula Mg3(Si2O5)(OH)4. These two minerals form a series; intermediate compositions are possible, with varying proportions of nickel to magnesium.

The mineralogy of Mars is the chemical composition of rocks and soil that encompass the surface of Mars. Various orbital crafts have used spectroscopic methods to identify the signature of some minerals. The planetary landers performed concrete chemical analysis of the soil in rocks to further identify and confirm the presence of other minerals. The only samples of Martian rocks that are on Earth are in the form of meteorites. The elemental and atmospheric composition along with planetary conditions is essential in knowing what minerals can be formed from these base parts.

Ekplexite is a unique sulfide-hydroxide niobium-rich mineral with the formula (Nb,Mo)S2•(Mg1−xAlx)(OH)2+x. It is unique because niobium is usually found in oxide or, eventually, silicate minerals. Ekplexite is a case in which chalcophile behaviour of niobium is shown, which means niobium present in a sulfide mineral. The unique combination of elements in ekplexite has to do with its name, which comes from a Greek world on "surprise". The other example of chalcophile behaviour of niobium is edgarite, FeNb3S6, and both minerals were found in the same environment, which is a fenitic rock of Mt. Kaskasnyunchorr, Khibiny Massif, Kola Peninsula, Russia. Analysis of the same rock has revealed the presence of two analogues of ekplexite, kaskasite (molybdenum-analogue) and manganokaskasite (molybdenum- and manganese-analogue). All three minerals belong to the valleriite group, and crystallize in the trigonal system with similar possible space groups.