Related Research Articles

Tantra is an esoteric yogic tradition that developed on the Indian subcontinent from the middle of the 1st millennium CE onwards in both Hinduism and Buddhism.

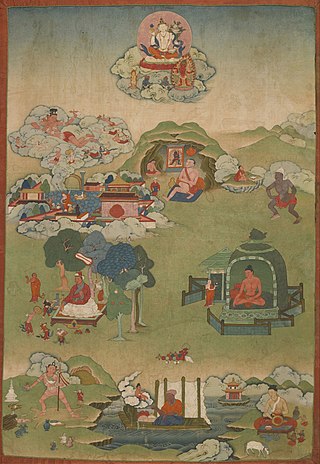

Vajrayāna, also known as Mantrayāna, Mantranāya, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, is a Buddhist tradition of tantric practice that developed in the Indian subcontinent and spread to Tibet, Nepal, other Himalayan states, East Asia, and Mongolia.

Tantric sex or sexual yoga refers to a range of practices in Hindu and Buddhist tantra that utilize sexuality in a ritual or yogic context. Tantric sex is associated with antinomian elements such as the consumption of alcohol, and the offerings of substances like meat to deities. Moreover, sexual fluids may be viewed as power substances and used for ritual purposes, either externally or internally.

Shaktism is one of the several major Hindu denominations wherein the metaphysical reality, or the godhead, is considered metaphorically to be a woman.

Tara, Ārya Tārā, also known as Jetsün Dölma, is an important figure in Buddhism, especially revered in Vajrayana Buddhism and Mahayana Buddhism. She appears as a female bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism, and is considered to be the consort or shakti (power) of Avalokiteshvara. Tārā is also known as a saviouress who hears the cries of beings in saṃsāra and saves them from worldly and spiritual danger.

A ḍākinī is a type of female spirit, goddess, or demon in Hinduism and Buddhism.

A ganacakra is also known as tsok, ganapuja, cakrapuja or ganacakrapuja. It is a generic term for various tantric assemblies or feasts, in which practitioners meet to chant mantra, enact mudra, make votive offerings and practice various tantric rituals as part of a sādhanā, or spiritual practice. The ganachakra often comprises a sacramental meal and festivities such as dancing, spirit possession, and trance; the feast generally consisting of materials that were considered forbidden or taboo in medieval India like meat, fish, and wine. As a tantric practice, forms of gaṇacakra are practiced today in Hinduism, Bön and Vajrayāna Buddhism.

A yogini is a female master practitioner of tantra and yoga, as well as a formal term of respect for female Hindu or Buddhist spiritual teachers in the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and Greater Tibet. The term is the feminine Sanskrit word of the masculine yogi, while the term "yogin" IPA:[ˈjoːɡɪn] is used in neutral, masculine or feminine sense.

Vajrayoginī is an important figure in Buddhism, especially revered in Tibetan Buddhism. In Vajrayana she is considered a female Buddha and a ḍākiṇī. Vajrayoginī is often described with the epithet sarvabuddhaḍākiṇī, meaning "the ḍākiṇī [who is the Essence] of all Buddhas". She is an Anuttarayoga Tantra meditational deity (iṣṭadevatā) and her practice includes methods for preventing ordinary death, intermediate state (bardo) and rebirth (samsara) by transforming them into paths to enlightenment, and for transforming all mundane daily experiences into higher spiritual paths.

Buddhist tantric literature refers to the vast and varied literature of the Vajrayāna Buddhist traditions. The earliest of these works are a genre of Indian Buddhist tantric scriptures, variously named Tantras, Sūtras and Kalpas, which were composed from the 7th century CE onwards. They are followed by later tantric commentaries, original compositions by Vajrayana authors, sādhanas, ritual manuals, collections of tantric songs (dohās) odes (stotra), or hymns, and other related works. Tantric Buddhist literature survives in various languages, including Sanskrit, Tibetan, and Chinese. Most Indian sources were composed in Sanskrit, but numerous tantric works were also composed in other languages like Tibetan and Chinese.

Tibetan tantric practice, also known as "the practice of secret mantra", and "tantric techniques", refers to the main tantric practices in Tibetan Buddhism. The great Rime scholar Jamgön Kongtrül refers to this as "the Process of Meditation in the Indestructible Way of Secret Mantra" and also as "the way of mantra," "way of method" and "the secret way" in his Treasury of Knowledge. These Vajrayāna Buddhist practices are mainly drawn from the Buddhist tantras and are generally not found in "common" Mahayana. These practices are seen by Tibetan Buddhists as the fastest and most powerful path to Buddhahood.

Women in Buddhism is a topic that can be approached from varied perspectives including those of theology, history, anthropology, and feminism. Topical interests include the theological status of women, the treatment of women in Buddhist societies at home and in public, the history of women in Buddhism, and a comparison of the experiences of women across different forms of Buddhism. As in other religions, the experiences of Buddhist women have varied considerably.

Songs of realization, or Songs of Experience, are sung poetry forms characteristic of the tantric movement in both Vajrayana Buddhism and in Hinduism. Doha is also a specific poetic form. Various forms of these songs exist, including caryagiti, or 'performance songs' and vajragiti, or 'diamond songs', sometimes translated as vajra songs and doha, also called doha songs, distinguishing them from the unsung Indian poetry form of the doha. According to Roger Jackson, caryagiti and vajragiti "differ generically from dohās because of their different context and function"; the doha being primarily spiritual aphorisms expressed in the form of rhyming couplets whilst caryagiti are stand-alone performance songs and vajragiti are songs that can only be understood in the context of a ganachakra or tantric feast. Many collections of songs of realization are preserved in the Tibetan Buddhist canon, however many of these texts have yet to be translated from the Tibetan language.

Kali or Kalika is a major Hindu goddess associated with time, change, creation, power, destruction and death in Shaktism. Kali is the first of the ten Mahavidyas in the Hindu tantric tradition.

Shmashana Adhipati is a name given to a deity either male or female and also together as a consort, who rules Shmashana, cremation ground. The Shamashana Adhipati literally translates to Lord of Shmashana. The name Shmashan Adhipathi is given to different deities in Hinduism and Tibetan Buddhism.

Karmamudrā is a Vajrayana Buddhist technique which makes use of sexual union with a physical or visualized consort as well as the practice of inner heat (tummo) to achieve a non-dual state of bliss and insight into emptiness. In Tibetan Buddhism, proficiency in inner heat yoga is generally seen as a prerequisite to the practice of karmamudrā.

Buddhist feminism is a movement that seeks to improve the religious, legal, and social status of women within Buddhism. It is an aspect of feminist theology which seeks to advance and understand the equality of men and women morally, socially, spiritually, and in leadership from a Buddhist perspective. The Buddhist feminist Rita Gross describes Buddhist feminism as "the radical practice of the co-humanity of women and men."

Classes of Tantra in Tibetan Buddhism refers to the categorization of Buddhist tantric scriptures in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism inherited numerous tantras and forms of tantric practice from medieval Indian Buddhist Tantra. There were various ways of categorizing these tantras in India. In Tibet, the Sarma schools categorize tantric scriptures into four classes, while the Nyingma (Ancients) school use six classes of tantra.

Shaman Hatley is a scholar of Asian religions, specializing in the goddess cults and tantric rituals of medieval India, including the yogini cults and the history of yoga.

Prajñāpāramitā Devī is a Mahayana Buddhist deity which is the personification of Prajñāpāramitā. This is the highest kind of wisdom in Mahayana which leads to Buddhahood and is the source of Buddhahood. This is the key topic of the Prajñāpāramitā sutras, and as such, Prajñāpāramitā Devī is also a personification of these important scriptures. She is also known as "Mother of Buddhas" or "The Great Mother".

References

- 2006 Foreword INDIES Winners in Religion (Adult Nonfiction). (n.d.). Foreword Reviews. Retrieved August 20, 2022, from https://www.forewordreviews.com/awards/winners/2006/religion/

- “Miranda Shaw.” Religious Studies, University of Richmond, https://religiousstudies.richmond.edu/faculty/mshaw/. Accessed 31 July 2022.

- Child, L. (2013). Relationships and visions: The yoginī as deity and human female in tantric Buddhism. In I. Keul (Ed.), “Yogini” in South Asia: Interdisciplinary Approaches. Routledge.

- Davis, K. (2010, August 10). Buddhist Goddesses of India by Miranda Shaw Book Review. Devata.Org - Apsara & Devata of Angkor Wat. http://www.devata.org/buddhist-goddesses-of-india-by-miranda-shaw-book-review/

- Edwards, C. (2002). A Few Notes on Norman Dubie’s The Spirit Tablets at Goa Lake. Blackbird, 1(2). https://blackbird.vcu.edu/v1n2/poetry/dubie_n/notes.htm

- Gray, D. B. (2008). Buddhist Goddesses of India. By Miranda Shaw. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 76(2), 486–488. doi : 10.1093/jaarel/lfn019

- Hall, D. A. (2013). The Buddhist Goddess Marishiten: A Study of the Evolution and Impact of her Cult on the Japanese Warrior. Brill. http://brill.com/view/title/21972

- LaMothe, K. L. (2017). Dancing on earth. Dance, Movement & Spiritualities, 4(2), 137–145. doi : 10.1386/dmas.4.2.137_7

- Pearlman, E. (1994). Liberating Sexuality: Miranda Shaw Talks about Tantra. Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. https://tricycle.org/magazine/liberating-sexuality/

- Poss, J. L. (2020). Miranda E. Shaw: A passionate path of women’s active contributions to Tantric Buddhism. In C. D. Hartung (Ed.), Claiming Notability for Women Activists in Religion (pp. 41–59). ATLA Open Press.

- Samdarshi, P. (2014). The Concept of Goddesses in Buddhist Tantra Traditions. The Delhi University Journal of the Humanities & the Social Sciences, 1, 87–99.