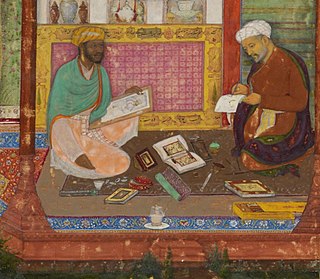

Muhammad Zaman ibn Haji Yusuf Qumi, known as Mohammad Zaman (fl. 1650 – c. 1700), [1] was a famous Safavid calligrapher and painter.

Muhammad Zaman ibn Haji Yusuf Qumi, known as Mohammad Zaman (fl. 1650 – c. 1700), [1] was a famous Safavid calligrapher and painter.

Mohammad Zaman was born in Kerman, Persia to Haji Yusuf, and received his education in Tabriz. [2] For his great intelligence, he was sent by Shah Abbas II of Persia to Rome to study Italian painting, and there he converted to Christianity. In his conversion he took the name of Paul and became Paolo Zaman. When he returned to Persia he was forced to flee to India because of his Christianity. In India, he became a refugee, or mansabdar, and obtained the protection of the Mughul dynasty under the emperor Shah Jahan [3] and later Dara Shikoh.

He lived mostly in Kashmir, but was invited to go to Dehli with other mansabdars by the Aurangzeb. In Dehli around the year 1660 CE, he met Niccolao Manucci, a Venetian traveler who wrote accounts of the Mughal rule. Mohammad Zaman returned to Persia around the years 1672-73 and embraced Islam once again. After re-establishing his reputation and making the Islamic pilgrimage, he received the title of "haji" like his father. He then worked in the city of Isfahan from 1675 to 1678. [2]

| Year | Title | Medium | Dimensions | Current Location | Place of Creation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1660-1675 CE | The Night Halt (Saint Petersburg Album Page) | Ink, colors and gold on paper | 13.5 x 20.1 in. (34.5 x 51 cm) | Louvre Museum | Iran [4] |

| 1663-1664 C.E. | Blue Iris | Ink, opaque watercolor on paper; gilded borders | Sheet: 13 1/16 x 8 3/8 in. (33.2 x 21.3 cm) | Brooklyn Museum | Isfahan, Iran [5] |

| 1663–69 CE | Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Firdausi | Opaque watercolor, ink, silver and gold on paper | 18 1/2 x 11 1/8 in. (47 x 28.2 cm) | Metropolitan Museum of Art | Likely Isfahan, Iran [6] |

| 1664–65 CE | A Night-time Gathering | Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper | Page: 13 1/8 x 8 1/4 in. (33.3 x 21 cm) Mat: 19 1/4 in x 14 1/4 in. (48.9 x 36.2 cm) | Metropolitan Museum of Art | Iran or India [7] |

| 1675-76 CE | Bahram Gur proves his worthiness by killing a dragon and recovering treasure from a cave (in Khamsa of Nizami) [8] | Painting on paper | 8.6 x 7.1 in (21.9 x 18.1 cm) [9] | The British Library | Safavid Iran |

| 1675-76 CE | Episode from the Indian Princess’s story: King Turktazi’s visit to the magical garden of Turktaz, Queen of the Faeries (in Khamsa of Nizami) [10] | Painting on paper | 9.9 x 7.1 in (25.2 x 18 cm) [9] | The British Library | Safavid Iran |

| 1675-76 CE | The servant girl Fitnah impresses Bahram Gur with her strength by carrying an ox on her shoulders (in Khamsa of Nizami) [11] | Painting on paper | 8.3 x 5.1 in (21 x 13 cm) [9] | The British Library | Mazandaran Province |

| 1675-1676 CE | The sīmurgh arrives to assist Rūdāba with the birth of Rustam, from the Book of Kings (Shāhnāma) | Pigment, gold pigment, and ink on paper | 408 mm x 261 mm | Chester Beatty Library | Isfahan, Iran [12] |

| 1675-1676 CE | Salm and Tūr organise the murder of their brother Īraj, from the Book of Kings (Shāhnāma) | Pigment, gold pigment, and ink on paper | 408 mm x 262 mm | Chester Beatty Library | Isfahan, Iran [13] |

| 1676 CE | Majnun visited by his father [14] | Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper. | Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Lent by The Art and History Collection | Isfahan, Iran | |

| 1680 CE | Judith with the Severed Head of Holofernes | Ink, gold and opaque watercolor on paper; mounted as an album page on card | Page: 13.1 x 8.2 in (33.5 x 21 cm) Painting excluding floral paneling: 7.9 x 6.6 in (20.1 x 17 cm) | The Khalili Collection of Islamic Art | Isfahan, Iran [15] |

Six of his paintings from 1678 to 1689 were of Biblical scenes. A painting of Judith with the severed head of Holofernes, currently in the Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, is signed "Ya sahib al-zaman", one of the titles of the 12th Shia Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi. Mohammad Zaman used this phrase in place of a signature, and on that basis the painting is attributed to him. [16] [17]

Mohammad Zaman favored night scenes, and his work combined multiple influences, drawing subjects from European paintings but with Mughal or Kashmiri stylistic touches. [16] He introduced a European style to Safavid painting in manuscripts known as farangi-sazi. [18] This style combines Persian iconography and compositional elements with more European elements, such as chiaroscuro, atmospheric effect, and “Western” perspective. The style could also be seen in his forest scenes, which include exaggerated forms, heavy contrasts between light and dark, and picturesque mountains and streams. [9]

The Khamsa of Nizami, a manuscript of five poems by poet Nizami Ganjavi, is known for its Safavid illustrations—three of which are attributed to Mohammad Zaman. It has been suggested that he produced these paintings in the 17th century as additions to the original manuscript. It is also suggested that the paintings by Mohammad Zaman were inserted in the Khamsa of Nizami after being removed from somewhere else, as there is some damage to the upper sections. His signature and the date inscription can be found on two of the paintings, however all three resemble another painting attributed to Mohammad Zaman, "Majnun in the Wilderness." [19]

Mohammad Zaman's depiction of the tale of Bahram Gur and the Indian Princess features wingless faeries, different from other depictions of the scene. The text adjacent to the image is a section of the Tale of the Indian Princess, which ends with a description of food and wine for a banquet in the King and Queen's pavilion. However, Mohammad Zaman's depiction does not include this pavilion scene, instead depicting King Turktazi and the Queen of the Faeries. [9]

The Shahnameh, also transliterated Shahnama, is a long epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi between c. 977 and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,000 distichs or couplets, the Shahnameh is one of the world's longest epic poems, and the longest epic poem created by a single author. It tells mainly the mythical and to some extent the historical past of the Persian Empire from the creation of the world until the Muslim conquest in the seventh century. Iran, Azerbaijan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and the greater region influenced by Persian culture such as Armenia, Dagestan, Georgia, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan celebrate this national epic.

Nizami Ganjavi, Nizami Ganje'i, Nizami, or Nezāmi, whose formal name was Jamal ad-Dīn Abū Muḥammad Ilyās ibn-Yūsuf ibn-Zakkī, was a 12th-century Muslim poet. Nizami is considered the greatest romantic epic poet in Persian literature, who brought a colloquial and realistic style to the Persian epic. His heritage is widely appreciated in Afghanistan, Republic of Azerbaijan, Iran, the Kurdistan region and Tajikistan.

A Persian miniature is a small Persian painting on paper, whether a book illustration or a separate work of art intended to be kept in an album of such works called a muraqqa. The techniques are broadly comparable to the Western Medieval and Byzantine traditions of miniatures in illuminated manuscripts. Although there is an equally well-established Persian tradition of wall-painting, the survival rate and state of preservation of miniatures is better, and miniatures are much the best-known form of Persian painting in the West, and many of the most important examples are in Western, or Turkish, museums. Miniature painting became a significant genre in Persian art in the 13th century, receiving Chinese influence after the Mongol conquests, and the highest point in the tradition was reached in the 15th and 16th centuries. The tradition continued, under some Western influence, after this, and has many modern exponents. The Persian miniature was the dominant influence on other Islamic miniature traditions, principally the Ottoman miniature in Turkey, and the Mughal miniature in the Indian sub-continent.

Khosrow and Shirin is the title of a famous tragic romance by the Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi (1141–1209), who also wrote Layla and Majnun. It tells a highly elaborated fictional version of the story of the love of the Sasanian king Khosrow II for the Christian Shirin, who becomes queen of Persia. The essential narrative is a love story of Persian origin which was already well known from the great epico-historical poem the Shahnameh and other Persian writers and popular tales, and other works have the same title.

'Abd al-Ṣamad or Khwaja 'Abd-us-Ṣamad was a 16th century painter of Persian miniatures who moved to India and became one of the founding masters of the Mughal miniature tradition, and later the holder of a number of senior administrative roles. 'Abd's career under the Mughals, from about 1550 to 1595, is relatively well documented, and a number of paintings are authorised to him from this period. From about 1572 he headed the imperial workshop of the Emperor Akbar and "it was under his guidance that Mughal style came to maturity". It has recently been contended by a leading specialist, Barbara Brend, that Samad is the same person as Mirza Ali, a Persian artist whose documented career seems to end at the same time as Abd al-Samad appears working for the Mughals.

The Persian word Falnama covers two forms of bibliomancy used historically in Iran, Turkey, and India. Quranic Falnamas were sections at the end of Quran manuscripts used for fortune-telling based on a grid. In the 16th century, Falnama manuscripts were introduced that used a different system; individuals performed purification rituals, opened a random page in the book and interpreted their fortune in light of the painting and its accompanying text. Only a few illustrated Falnamas now survive; these were commissioned by rich patrons and are unusually large books for the time, with bold, finely executed paintings. These paintings illustrate historical and mythological figures as well as events and figures associated with the Abrahamic religions.

The illuminated manuscript Khamsa of Nizami British Library, Or. 12208 is a lavishly illustrated manuscript of the Khamsa or "five poems" of Nizami Ganjavi, a 12th-century Persian poet, which was created for the Mughal Emperor Akbar in the early 1590s by a number of artists and a single scribe working at the Mughal court, very probably in Akbar's new capital of Lahore in North India, now in Pakistan. Apart from the fine calligraphy of the Persian text, the manuscript is celebrated for over forty Mughal miniatures of the highest quality throughout the text; five of these are detached from the main manuscript and are in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore as Walters Art Museum MS W.613. The manuscript has been described as "one of the finest examples of the Indo-Muslim arts of the book", and "one of the most perfect of the de luxe type of manuscripts made for Akbar".

The Khamsa or Panj Ganj is the main and best known work of Nizami Ganjavi.

Ali Asghar was one of the prominent Emir and nobleman during the Mughal empire. He was entitled 'Khan Zaman Khan Bahadur' by Emperor Farrukhsiyar. He remained in many important posts during the successive rules of Bahadur Shah I, Jahandar Shah, Farrukhsiyar, Rafi ud Darajat, Shah Jahan II and Muhammad Shah.

Prince Ibrahim Mirza, Solṭān Ebrāhīm Mīrzā, in full Abu'l Fat'h Sultan Ibrahim Mirza was a Persian prince of the Safavid dynasty, who was a favourite of his uncle and father-in-law Shah Tahmasp I, but who was executed by Tahmasp's successor, the Shah Ismail II. Ibrahim is now mainly remembered as a patron of the arts, especially the Persian miniature. Although most of his library and art collection was apparently destroyed by his wife after his murder, surviving works commissioned by him include the manuscript of the Haft Awrang of the poet Jami which is now in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

Aliquli Jabbadar was an Iranian artist, one of the first to have incorporated European influences in the traditional Safavid-era miniature painting. He is known for his scenes of the Safavid courtly life, especially his careful rendition of the physical setting and of details of dress.

Mo'en Mosavver or Mu‘in Musavvir was a Persian miniaturist, one of the most significant in 17th-century Safavid Iran. Not much is known about the personal life of Mo'en, except that he was born in ca. 1610-1615, became a pupil of Reza Abbasi, the leading painter of the day, and probably died in 1693. Over 300 miniatures and drawings attributed to him survive. He was a conservative painter who partly reversed the advanced style of his master, avoiding influences from Western painting. However, he painted a number of scenes of ordinary people, which are unusual in Persian painting.

Aqa Mirak was a Persian illustrator and painter.

Mir Musavvir was a Persian painter at the Safavid court at Tabriz and later the Mughal court at Kabul. During his time at the royal Safavid workshop, he contributed to the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp. He was the father of Mir Sayyid Ali, who adopted his occupation of painting.

The Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp or Houghton Shahnameh is one of the most famous illustrated manuscripts of the Shahnameh, the national epic of Greater Iran, and a high point in the art of the Persian miniature. It is probably the most fully illustrated manuscript of the text ever produced. When created, the manuscript contained 759 pages, 258 of which were miniatures. These miniatures were hand-painted by the artists of the royal workshop in Tabriz under rulers Shah Ismail I and Shah Tahmasp I. Upon its completion, the Shahnameh was gifted to Ottoman Sultan Selim II in 1568. The page size is about 48 x 32 cm, and the text written in Nastaʿlīq script of the highest quality. The manuscript was broken up in the 1970s and pages are now in a number of different collections around the world.

The Great Mongol Shahnameh also known as the Demotte Shahnameh or Great Ilkhanid Shahnama, is an illustrated manuscript of the Shahnameh, the national epic of Greater Iran, probably dating to the 1330s. In its original form, which has not been recorded, it was probably planned to consist of about 280 folios with 190 illustrations, bound in two volumes, although it is thought it was never completed. It is the largest early book in the tradition of the Persian miniature, in which it is "the most magnificent manuscript of the fourteenth century", "supremely ambitious, almost awe-inspiring", and "has received almost universal acclaim for the emotional intensity, eclectic style, artistic mastery and grandeur of its illustrations".

Āzādeh is a Roman slave-girl harpist in Shahnameh and other works in Persian literature. When Bahram-e Gur was in al-Hirah, Azadeh became his favorite companion. She always accompanies Bahram in hunting.

Timurid art is a style of art originating during the rule of the Timurid Empire (1370-1507) and was spread across Iran and Central Asia. Timurid art was noted for its usage of both Persian and Chinese styles, as well as for taking influence from the art of other civilizations in Central Asia. Scholars regard this time period as an age of cultural and artistic excellence. After the decline of the Timurid Empire, the art of the civilization continued to influence other cultures in West and Central Asia.

Farangi-Sazi was a style of Persian painting that originated in Safavid Iran in the second half of the 17th century. This style of painting emerged during the reign of Shah Abbas II, but first became prominent under Shah Solayman I.

The Iskandarnameh is a poetic production in the Alexander Romance tradition authored by the Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi that describes Alexander the Great as an idealized hero, sage, and king. More uniquely, he is also a seeker of knowledge who debates with great philosophers Greek and Indian philosophers, one of them being Plato.