Related Research Articles

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse committed with the necessary intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisdiction. This state of mind may, depending upon the jurisdiction, distinguish murder from other forms of unlawful homicide, such as manslaughter. Manslaughter is killing committed in the absence of malice, such as in the case of voluntary manslaughter brought about by reasonable provocation, or diminished capacity. Involuntary manslaughter, where it is recognized, is a killing that lacks all but the most attenuated guilty intent, recklessness.

French law has a dual jurisdictional system comprising private law, also known as judicial law, and public law.

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th century BC.

Laws regarding incest vary considerably between jurisdictions, and depend on the type of sexual activity and the nature of the family relationship of the parties involved, as well as the age and sex of the parties. Besides legal prohibitions, at least some forms of incest are also socially taboo or frowned upon in most cultures around the world.

In Italy the penal code regulates intentional homicide, "praeterintention" homicide corresponding to the Anglo-Saxon Felony-Murder, and manslaughter. <<Thus - to summarize - we see that murder includes murder committed with the intention of producing [...] serious injury, or with the intention of producing that which either can easily produce the other and, therefore, also includes cases in which death is preceded by criminal intent and which is the consequence of an illegal act, which by its nature constitutes a crime. Involuntary manslaughter, however, includes homicide caused by omission, involuntary manslaughter, accidental homicide resulting from an unlawful act which is not a crime, and the like>>.

Under Dutch law, moord (murder) is the intentional and premeditated killing of another person. Murder is punishable by a maximum sentence of life imprisonment, which is the longest prison sentence the law will allow for, unless the sentence is commuted or pardoned by the Sovereign of the Netherlands. However, this happens and few appeals to the King for clemency have ever been successful.

Serge Guinchard is a French jurist who formerly taught at the Law School of Dakar and Jean Moulin University Lyon 3 and most recently at Panthéon-Assas University, where he is now Professor emeritus. He has also held political posts in the metropolitan government of Lyon.

The Tribunal judiciaire de Paris, located at the Judicial Campus of Paris in Batignolles, is the largest court in France by caseload. It replaced the capital's former Tribunal de grande instance and Tribunal d'instance under an amalgamation of jurisdictions that came into effect on January 1, 2020.

Criminal responsibility in French criminal law is the obligation to answer for infractions committed and to suffer the punishment provided by the legislation that governs the infraction in question.

In France, a cour d’appel of the ordre judiciaire (judiciary) is a juridiction de droit commun du second degré, a. It examines judgements, for example from the correctional tribunal or a tribunal de grande instance. When one of the parties is not satisfied with the verdict, it can appeal. While communications from jurisdictions of first instance are termed "judgements", or judgments, a court of appeal renders an arrêt (verdict), which may either uphold or annul the initial judgment. A verdict of the court of appeal may be further appealed en cassation. If the appeal is admissible at the cour de cassation, that court does not re-judge the facts of the matter a third time, but may investigate and verify whether the rules of law were properly applied by the lower courts.

In France, the correctional court is the court of first instance that has jurisdiction in criminal matters regarding offenses classified as délits committed by an adult. In 2013, French correctional courts rendered 576,859 judgments and pronounced 501,171 verdicts.

TheCode pénal is the codification of French criminal law. It took effect March 1, 1994 and replaced the French Penal Code of 1810, which had until then been in effect. This in turn has become known as the "old penal code" in the rare decisions that still need to apply it.

The Penal Transaction Law is a Belgian law that allows a court to end a public prosecution in exchange for the payment of a sum of money. The law is often enacted to expedite trials where a successful prosecution is in doubt, or in cases that are likely going to be lengthy and protracted, or are at risk of being delayed. The settlement does not equal a conviction, and does not appear on the criminal record of those under investigation. Under article 2046 of the Civil Code, the right to propose a settlement rests exclusively with the Public Prosecutor at any time during the proceedings.

French criminal law is "the set of legal rules that govern the State's response to offenses and offenders". It is one of the branches of the juridical system of the French Republic. The field of criminal law is defined as a sector of French law, and is a combination of public and private law, insofar as it punishes private behavior on behalf of society as a whole. Its function is to define, categorize, prevent, and punish criminal offenses committed by a person, whether a natural person or a legal person. In this sense it is of a punitive nature, as opposed to civil law in France, which settles disputes between individuals, or administrative law which deals with issues between individuals and government.

A criminal proceeding in French law is one carried out in the name of society against a person accused of a criminal offense by applying the French penal code. It is taken in the name of society, in that its goal is to stop disruption of public order, and not to abate personal damages done to a specific person, which is governed by French civil law.

The principle of legality in French criminal law holds that no one may be convicted of a criminal offense unless a previously published legal text sets out in clear and precise wording the constituent elements of the offense and the penalty which applies to it. (Latin:Nullum crimen, nulla pœna sine lege, in other words, "no crime, no penalty, without a law").

French criminal procedure focuses on how individuals accused of crimes are dealt with in the French criminal justice system: how people are investigated, prosecuted, tried, and punished for an infraction defined in the penal code. These procedural issues are codified in the French code of criminal procedure. It is the procedural arm of French criminal law.

This glossary of French criminal law is a list of explanations or translations of contemporary and historical concepts of criminal law in France.

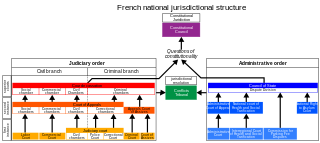

Jurisdictional dualism in France is the separation of the French court system into two separate divisions, or "ordres", as they are called in French: the ordinary courts, and the administrative courts. The ordinary courts, also known as the judiciary order, handle criminal and civil cases, while the administrative courts handle disputes between individuals and the government. This dual system allows for a clear separation of powers and specialized handling of cases related to the actions of the government. The administrative courts are headed by the Council of State, and the ordinary courts by the Court of Cassation for judiciary law.

The French code of criminal procedure is the codification of French criminal procedure, "the set of legal rules in France that govern the State's response to offenses and offenders". It guides the behavior of police, prosecutors, and judges in how to deal with a possible crime. The current code was established in 1958, and replaced the code of 1808, created under Napoleon.

References

- ↑ "Article 132-18". Legifrance. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

- ↑ "Article 221-1 - Code pénal - Légifrance". www.legifrance.gouv.fr. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ↑ Corioland, Sophie (2019-01-08). Droit pénal général (in French). Editions Ellipses. ISBN 978-2-340-03229-3.

- ↑ "Article 221-2". Legifrance. Archived from the original on 2007-11-02. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ↑ "Chapitre Ier : Des atteintes à la vie de la personne (Articles 221-1 à 221-11-1) - Légifrance".

- ↑ "Article 221-3". Legifrance. Archived from the original on 2007-11-02. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Pradel, Jean (2016-09-14). Droit pénal comparé. 4e éd (in French). Editis - Interforum. ISBN 978-2-247-15085-4.

- ↑ Government, Frrench (2017-06-26). Criminal Law of France. Independently Published. ISBN 978-1-5215-9028-7.

- ↑ "Section 1 : Des atteintes volontaires à la vie (Articles 221-1 à 221-5-5) - Légifrance".

- ↑ McKillop, Bron (1997). Anatomy of a French Murder Case. Hawkins Press. ISBN 978-1-876067-06-9.

- ↑ Hodgson, Jacqueline (2005-11-08). French Criminal Justice: A Comparative Account of the Investigation and Prosecution of Crime in France. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84731-069-9.

- ↑ The French Parliament. "Loi n° 2007-1198 du 10 août 2007 renforçant la lutte contre la récidive des majeurs et des mineurs". French Criminal Law (in French). Legifrance. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ↑ The French Parliament. "Paragraph 1 - Conditions for the granting of ordinary suspension". French Criminal Law. Legifrance. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ↑ "Article 222-7 - Code pénal - Légifrance". www.legifrance.gouv.fr. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ↑ Bouloc, Bernard (2023-10-12). Droit pénal général 28ed (in French). Groupe Lefebvre Dalloz. ISBN 978-2-247-22940-6.

- ↑ Pin, Xavier (2023-10-12). Droit pénal général 2024 15ed (in French). Groupe Lefebvre Dalloz. ISBN 978-2-247-22928-4.

- ↑ "La Praeterintention" (PDF). Penale.it. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ↑ "Article 222-8 - Code pénal - Légifrance". www.legifrance.gouv.fr. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ↑ Elliott, Catherine (2001-05-01). French Criminal Law. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-99314-6.

- ↑ Maréchal, Jean-Yves (2003). Essai sur le résultat dans la théorie de l'infraction pénale (in French). L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-7475-4549-5.

- ↑ Tsikarishvili, Kakha (2017-12-31). "Particularities of Subjective Element of the Crime in French Criminal Law". Journal of Law (2). ISSN 2720-782X.